Timing is everything. Just ask Microsoft. They were small in 1981, but when IBM came looking for an operating system, Microsoft happened to be available when larger software companies were not. Microsoft wrote the OS for the hugely successful IBM PC and has never looked back.

Microsoft has now entered middle age, so to speak. New CEO Satya Nadella is by all accounts doing an amazing job. However, it hasn't been all smooth sailing under his watch, as we can see from Microsoft's 2015 income statement.

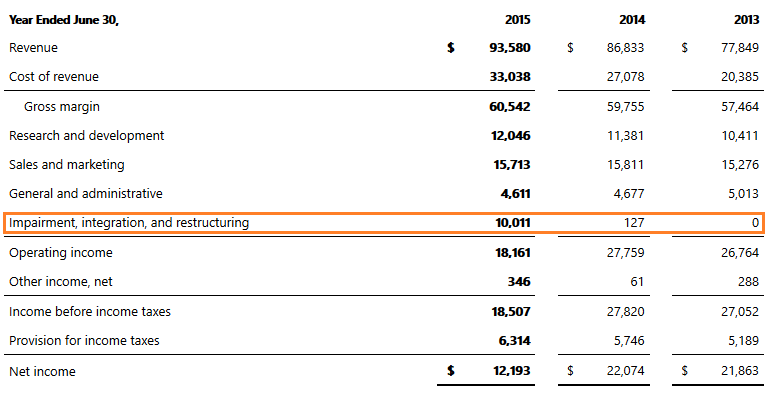

In my last article, we left off with a question about this particular line on the statement:

The highlighted line tells us that in 2015, Microsoft recorded a $10 billion expense for "Impairment, integration and restructuring." By anyone's standards, that's a massive hit. Before I explain what it means, let's just note that this single expense accounts for the entire drop in Microsoft's net income that year. Microsoft earned over $20 billion in each of 2013 and 2014, but in 2015 its net income dropped by $9.9 billion. Almost exactly the amount of the impairment expense.

what is an Impairment Charge?

An impairment charge is an expense recorded at the discretion of the company. It's how companies, in the language of accounting, apologize for something they once said.

This apology was pretty significant. I would have at least expected some flowers to go with it. Seeing half the earnings of the company disappear in a flash is pretty disconcerting to investors.

Investors in the stock market like predictability. All things being equal, they are willing to pay more for a stock that is stable than for one that fluctuates wildly in price, even if the average price is the same and they are both growing each year at the same rate. (Why? Because if you must sell your shares, you can predict the price of the stable stock. The price of volatile stock on any given day could be up or down. Down is not good, if you have to sell.)

Microsoft's financial statements are, on the whole, very steady. In fact, if you compare the figures for 2013, 2014, and 2015 across any row on the income statement, there is remarkable consistency everywhere except this one line.

Look at the revenue and cost of revenue lines. They grow in lock step from year to year, resulting in almost no change at all in gross margin. Gross margin is about $60 billion in each of the three years.

Look at the expenses. Research and development, growing slowly. Sales and marketing, virtually unchanged. General and administrative, slow decline. All in all, very stable.

That's what makes this impairment charge so remarkable. It is out of character for a middle-aged company.

If you look closely, there is a clue to the reason for the impairment charge. It's hidden in the stability of the gross margin. With revenue growing by 20% over two years, from $77.8 billion to $93.5 billion, the fact that gross margin did not change suggests a problem.

As you can see from the table, while the dollar value of the gross margin grew slightly $57 billion to $60 billion, on a percentage basis, it dropped substantially. It fell from 74% to 65% of revenue.

Why?

The reason is fairly simple. In 2015, Microsoft wasn't selling the same products as in 2013. It was now selling more devices. Cellphones, to be precise. And producing one more cellphone for sale costs a lot more than producing one more copy of Microsoft Office.

Let there be Lumia!

In 2014, former CEO Steve Ballmer tried to make his mark on Microsoft. Ballmer was a long-time Microsoft employee. He had been at the meeting with Bill Gates in 1981 when they clinched the pivotal contract with IBM. He had seen Microsoft become very rich selling software. The problem was, Apple was even richer, and Apple didn't just sell software, they sold iPhones.

I don't know Ballmer at all, of course, but it's hard not to think that Ballmer pictured himself as some sort of Steve Jobs, inspiring devoted customers with his product announcements.

In 2014, Ballmer decided that Microsoft needed to be in the cellphone business. So Microsoft bought Nokia Devices and Services. Nokia was nothing like the leading cellphone manufacturer that it had been prior to 2001. It was losing market share at an astonishing rate.

Microsoft, looking for a partner to run its cellphone operating system, had already loaned Nokia over $2 billion to help it produce the Lumia phone. Now Ballmer decided to go all in. Microsoft acquired Nokia for $9.4 billion.

Only $7.1 billion of this price was cash. Another $2.1 was Nokia buying back the loan that Microsoft had made to them earlier. The rest ($0.2 billion) was the amount of Nokia's other debts that Microsoft agreed to take over. (These details are in Note 9 of Microsoft's 2015 financial statements.)

Normally when a company makes a big investment like this, the purchase price doesn't show up as an expense on the income statement. Instead, it shows up on the balance sheet as an asset. Then every year, a portion of this asset gets moved over to the income statement as an expense. This is called amortization. It continues for as long as it takes to move the whole investment over to the incomes statement, one piece at a time, one year at a time.

Amortization is accounting's way of matching the expenditure (the investment) to the years in which it produces revenue. Microsoft bought Nokia's cellphone business in order to make money for years and years to come. Apart from the ego needs of senior executives, that's the reason any company makes any investment.

So the plan was to amortize the $9.4 billion expenditure over a whole bunch of years, as Microsoft raked in the money from sales of its fabulous cellphones.

This didn't happen.

In 2015, Microsoft's Board of Directors replaced Ballmer with a new CEO, Satya Nadella. Nadella decided that Ballmer's plan to rival Apple in the cellphone market wasn't going to work. The way of the future was the cloud. (And mobile. After all, Nadella still hasn't sold the cellphone division. He just moved it under the umbrella of the big Windows group.)

Nadella decided to tell the world that the $9.4 billion investment in Nokia's cellphone business was a big mistake. That's what the "Impairment, integration and restructuring" expense is all about. Nadella and his board of directors took the huge "cellphone business"asset off the balance sheet and moved it over to the income statement as an expense, all at once. No more amortizing the asset, no more trickling it out as an expense one year at a time. All at once. Gone.

This is a nice card to be able to play if you are Satya Nadella. It allows you to reverse the decision of your predecessor and basically put the blame on him. This big expense, coming less than a year after Nokia was acquired, is Nadella telling the world that Steve Ballmer got the Nokia decision wrong. Very wrong.

Note that this was discretionary. Microsoft did not have to do this. They still owned the asset. But now they are saying the asset is worthless.

Age of Persuasion

Nadella is trying to tell us a story. It's the opposite of Ballmer's story. Like any CEO or CFO, Nadella uses accounting to try to persuade us that his story is true.

Make no mistake about it, this is what accounting is for. Persuasion. If you think accounting is about presenting an objectively true picture of a company's finances, welcome to the world of adults. Accounting bears the same relationship to reality that Photoshop does. Sorry to break it to you.

Accounting lets Microsoft get away with this particular form of story telling because accounting assumes corporate executives are biased. It assumes they will naturally want to exaggerate how well their company is doing. It does not comprehend that managers sometimes have an incentive to tell the world how badly it is doing. Accounting does not realize that it provides an ideal vocabulary for blaming Steve Ballmer.

Who dunnit?

Let's look at the write-down of the $10 billion cellphone investment in more detail. Again, the notes to Microsoft's 2015 financial statements tell us much of what we need to know. The notes are always where the gory details are hidden.

The $10 billion is described on the income statement as "Impairment, integration, and restructuring." Here is what each of those terms means:

Impairment

The impairment component was the lion's share of the write-down, at $7.6 billion. This included $5.4 billion for goodwill, which is what companies call it when they pay more for a company than they can specifically identify. Steve Ballmer thought that buying Nokia's cellphone business would generate a lot of synergies with Microsoft's other businesses, so he was willing to spend $5.4 billion more buying Nokia than the component parts of the business were worth. Nadella disagreed with his assessment, so the $5.4 billion is gone. So too all the intangible assets that Microsoft acquired from Nokia, such as patents and engineering designs. They were valued by Ballmer at $2.2 billion. Nadella, not so much. Gone. The impairment charge is Microsoft trying to tell us that the assets will never achieve the synergies and earn the profits that Ballmer had hoped to achieve. Who is to say which Microsoft CEO is right? Nadella didn't sell off the cellphone business. He still kept it. And now, if it earns any money, the earnings have no recorded asset to match them. This means that Microsoft's return on assets (ROA) gets inflated in the future.

Integration

The integration component of the write-down is code for "layoffs." It amounts to $1.3 billion in severance packages and related costs. Why so much? Because Microsoft let 19,000 people go worldwide, including 13,000 who had worked for Nokia.

Restructuring

The restructuring component is also code for layoffs. It wasn't as big as the other components, amounting to "just" $0.78 billion. But it's still severance packages, for 7,800 more Microsoft employees. All let go.

The Moral of the Story

I know that the severance packages helped. Doing the math, the average severance package could have been as high as $100,000 per person ($780 million divided by 7,800 people). But not all of the expense would have gone to these employees. A lot would have gone to "outplacement" consultants who would have been well paid for breaking the bad news to the unwanted employees. And senior executives would have got way more than average, meaning that a lot of Microsoft employees would have received very little.

In all, 26,800 people lost their jobs. Don't let anyone tell you that investors bear all the risk in capitalism.

Video of Steve Ballmer is from Youtube.

Slight impairment of the left shifter cable at the 20,000 km mark. Photo taken in 2016.

Photo of the turtle amortizing its way across the road taken in 2016 near Bobcaygeon, Ontario.

Photo of a radically restructured house taken in 2015 in Fenelon Falls, Ontario. I think Buckminster Fuller would like this house.