In this lesson, we're going to talk about accountability. It is the point of accounting. Isn't it?

Here's what we're going to cover. We're going to look at accountability theory. We're going to talk about complex situations of accountability, and then about corporate accountability. Finally, I want to give you a tool to use, an analytical tool called the accountability cube, that I hope will be helpful to you in looking at accountability situations and trying to make sense of why accountability is or isn't happening.

So accountability theory first.

Accountability Theory

What do we mean by accountability? Well, to a certain extent, the meaning is obvious. Everybody knows what accountability means, but I want to try to unpack the notion of accountability and think about what is really required for accountability to happen.

Accountability is the point of accounting, right? We do accounting in order to create accountability of some kind. So we need to understand what we mean by accountability if we expect accounting to accomplish anything.

Suppose you give your kid $20. You send them to the store to buy some milk. You want to know, what did they do with the money that you gave them? Ideally, you want to see the milk, that's what you sent them to the store to get. But you're also going to want a receipt and you're going to want the change back from the $20 that you gave them. So in other words, your kid has to provide an account: "Here's what I accomplished with the $20."

Underlying Concepts

Let’s try to unpack some of the basic concepts that underly this seemingly simple notion of accountability.

Resources

Even if we look at this very basic scenario, we can see that there's a set of resources that are at play, and they are unevenly distributed. You've got $20 and the kid doesn't.

Power

And that puts you in a position of power. Because you have those resources, you have some kind of power over your kid, in that getting access to the $20 is contingent on them being able to be trusted with it. So that creates a situation of power.

Michel Foucault, looking, I must say, rather powerful (Credit: Wikimedia, public domain)

However, as Michel Foucault tells us, power is not something that's one way. It's actually constituted between two people. So your kid does have a response to the power that you get from giving them the $20:

Your kid has the opportunity to run off with the $20 and not come back.

Your kid has the potential to say, "No, I don't want to go to the store. I don't accept that task. I don't want to be responsible for the $20."

Your kid could go buy the milk and get a receipt, but on the way home, give the change from the $20 to some homeless person.

There's lots of things that your kid can do that transcend simply executing your instructions to the letter. If you don’t have kids, trust me on this.

Demand

There's also this notion of the ability to demand an account. As the person who gave the kid $20, you are demanding that the kid show you what they did with the money. But we also have to unpack that notion as well, because to a certain extent, your kid may want to provide an account in order to prove how trustworthy they are.

Consequences

There's also, in any accountability situation, a set of consequences that are at least implied. Even if they're not laid out in a contract, there are consequences. Depending on your model of parenting, if your kid isn’t able to account for the entire $20 and you suspect them of perhaps pocketing the balance of the $20 or using it to buying candy or whatever, you could perhaps punish them in some way or sit down and talk to them — that may be enough of a punishment for some kids! — or you could simply choose not to trust them with $20 anymore.

The consequences are going to be either explicit or they're going to be implied in your relationship to that point in time. Your kid will know what kinds of things happen when they no longer act in the way that you expected them to. It’s the same in other social contexts, too, such as the relationship between you and your boss.

Definitions

Let's look at some basic definitions of accountability that call in various ways on these underlying concepts.

The Dictionary Definition

If we turn to the dictionary, the Merriam-Webster dictionary that I’ve got bookmarked on my computer offers a couple of definitions. The first is "the quality or state of being accountable."

That's just a tautology, to me. It uses the word accountable to define accountability, so it doesn't really tell us anything.

A more useful definition is in the second part, "an obligation or willingness to accept responsibility or to account for one's actions."

There's a couple of things I like about this. First, it introduces a new word, responsibility. It's this notion of responsibility that underlies accountability.

But second, there's also this aspect of accounting for one's actions. The implication is that there's some sort of an audience in mind. This is important to understand: accountability is a social relationship.

Finally, there's also this notion mentioned at the beginning of the definition, an obligation or willingness. I like that wording because it gets at the possibility that someone might not want to provide an account, but they're obliged to; or the converse situation where someone actually wants to provide an account. These possibilities are often glossed over when we talk about accountability.

Some accounting researchers go with the broad definition that accountability is "the giving or receiving of accounts." This is similar to the first definition from the dictionary, in that it's quite tautological. For this reason, it doesn’t give us a lot of traction on the concept of accountability.

A More Detailed Definition

So, let's look at a more detailed definition that comes from a book chapter written by Bovens, Schillemans and Goodin in 2014.

Providing answers to those who have a right to demand answers

This right arises from a principal-agent relationship

Accounts are provided ex post

There are consequences

I like this because it begins to unpack some of the implied notions of accountability we have already touched on.

The first thing they suggest is that accountability has to do with providing answers to those who have a right to demand answers. It's interesting that they go straight to the idea of power: the right to demand answers. This has all kinds of implications for our understanding, for instance, of property rights. Where does this right to demand an answer arise? In the economic system that we live in, capitalism, this right comes from ownership.

Bovens et al. draw on the notion of a principal-agent relationship. Principal-agent theory is this notion in accounting research that really, really simplifies the idea of accountability. You got one person who owns things and you've got their agent, the person that they delegate to, who is responsible for executing the principal’s desires with regard to this piece of property or corporation or whatever it is that the principal owns.

This is a very, one-way sort of a relationship and it's extremely simplistic. This principal-agent notion of accountability dominates a lot of accounting research. It comes from the notions of property ownership and delegating responsibility. Bovens et al. incorporate this in their definition, alongside these other nuances listed above.

Bovens et al. also point out that in an accountability relationship, accounts are provided ex-post. That is, after the fact, you are expected to provide some sort of an account of what happened.

Again, this is pretty simplistic because there's lots of situations where the expectations for an account are negotiated up front. This means that a lot of accountability can happen before anything else. If we try to decide in advance what I am going to be allowed to do with your money, all of that kind of negotiation is missing from the definition given by Bovens et al.

Finally, they point out that there are consequences in an accountability relationship. The consequences could be anything from a positive incentive to a negative punishment, but there are consequences if there's accountability.

That’s the definition laid out by Bovens, Schillemans and Goodin. Despite the fact that some of the elements are simplistic, it’s actually a pretty good definition by the standards of a lot of mainstream accounting research. By drawing together these various aspects of accountability, Bovens et al. have actually ended up with a fairly nuanced package.

Assumptions

Let's look at some of the common assumptions underlying these “accepted” notions of accountability.

Binary

The first is that it's binary. Right. It involves two parties. One party is accountable to the other. I want to be able to talk to you today about situations where that's not actually the case, where it gets more complicated than that.

Hierarchical

There's also an implication of hierarchy, that one person is accountable to their boss. And accountability, I think is actually much richer and much deeper than that. It's not just a hierarchical relationship.

Involuntary

There's also this assumption that it's involuntary, that the person who has used to the resources doesn't want to provide an account. Accepted notions of accountability in accounting research tend to take a dim view of human nature. As we've seen, however, even in the most basic situation where you gave your kid $20, oftentimes they may want to provide an account to prove to you how trustworthy they are.

There is an alternative version of this assumption, which is that the person who has used the resources, the “agent” in the principal-agent relationship, does in fact want to provide the account, because they benefit financially from doing this. Like I said, the average accounting researcher takes a pretty dim view of human nature. Notions like altruism or empathy for others tend to be dismissed, I’m afraid.

Dischargeable

There's also a much more subtle implication or assumption in these definitions. And that's the idea that accountability is dischargeable. What I mean by that is the notion that if I provide my account to you, then my accountability to you is completed and I no longer have any further obligations. I have discharged my obligation.

We're going to find out, as we dig further into this, that accountability actually involves much richer and much more complex relationships that potentially can never be exhausted, where accountability can never be fully discharged.

For now, however, these are some of the basic assumptions underlying the simple notions of accountability that we see in a lot of accounting theory. Keep in mind that this is not intended to be an exhaustive list. I'm only listing some of the common assumptions. I'm sure if you dug into it further, you could uncover all kinds of other assumptions, but these are the four that I want to highlight here.

Complex Accountability

Let's turn to more complex notions of accountability, to see what happens in situations that just don't fit the binary, hierarchical relationships that are assumed in so much of accounting theory.

Social Accountability

The first complex example is social accountability. Suppose that someone is late for an important social event, for reasons beyond their control. Clearly, this is not a binary situation, right? There are often multiple people involved. You show up late to a wedding and there will be a whole bunch of people waiting impatiently, wondering where you’ve been. Or perhaps you arrive late in a car with several other people. Accountability can obviously very quickly transcend a one-to-one, principal-agent situation.

It's also non-hierarchical because friends and family are involved. Social accountability is often not about accountability to any kind of an authority figure.

There's also a very voluntary element here. If I show up late for a party, I might have more of a desire to provide an account to everyone, to explain why I’m late, than there is interest in hearing it. People at the party just want to get on with things. My desire to apologize effusively might actually detract from the occasion.

Finally, I don't think a situation like this involves an accountability that is fully dischargeable. Family members have a way of remembering when you turned up late for things and bringing it up later on, sometimes years later. So, there's not necessarily a sense in social accountability that the hurt you may have caused can be done away with simply by apologizing. People can hold a grievance for a long time. You know what families are like.

Inter-organizational Accountability

Here's a second complex example. By inter-organizational accountability, I mean accountability between two organizations. Obviously this is nonbinary, unless you want to treat the organization as a unitary entity, to reify it as some sort of a person or a being. This has happened, sadly, in US law. The idea that corporations are a “person” has been the subject of all kinds of litigation over campaign donations from corporations to their favorite politicians.

If we want to avoid this kind of problem in our own thinking, we need to recognize that any organization, including a corporation, is a collection of people. Inter-organizational accountability is many people being accountable to many other people. This helps us deconstruct the possible motives and intentions of a “corporation” and understand that accountability for corporate actions is highly complex.

Inter-organizational accountability is also often non-hierarchical. If you've got a partnership relationship between two organizations, or some sort of a contract between them, it’s not simply a matter of one corporation owning the other and directing it to take certain actions. Corporations collaborate in many non-hierarchical ways.

It's also often voluntary, rather than just something being demanded by one of the organizations. For instance, if another company is trying to comply with your company’s credit conditions or other contractual requirements, you usually want them to succeed. And they usually want their relationship with your company to continue, so they very much want to prove that they have been accountable for their part of the contract.

This is, however, a situation where accountability might be fully dischargeable, because the contract might stipulate exactly what's required in their account. And if they provide that, then contractually, you can both check the box and say they have been accountable. This is quite different from personal and social relationships.

Intra-organizational Accountability

Here's the third example of complex accountability: intra-organizational accountability, or in other words, accountability within an organization. You’d think that this is a quintessential example of simple accountability, with workers accountable to management in a way that meets all the elements we talked about: binary, between two people; hierarchical, in that one of them is the boss; involuntary, in that a failure to provide an account can cost you your job; and dischargeable: come pay day, everyone is even.

But there is also a network of informal peer-to-peer accountability relationships in any organization. A wonderful accounting scholar by the name of John Roberts first wrote about this in 1991, and he's published several papers on the topic since then where he writes about the role of social accountability in an organization. He contrasts this horizontal accountability inside an organization with the hierarchical accountability relationship that we often assume is the more important one.

Roberts talks about horizontal accountability being very much nonbinary. Accountability happens in social situations. At coffee breaks, for instance, you've got internal group dynamics, all these subtle peer-to-peer relationships combining in ways that, for instance, reinforce expectations of how to act in a corporation. This goes far beyond simply adhering to the rules. This is about coworkers collectively and often tacitly deciding what is their work group going to look like: “Are we the kind of group that shows up on time and gets right to work, or are we the kind of group that hangs around the water cooler and chats for half an hour before we get to work?”

This impacts all sorts of moral decision-making inside the organization, with massive implications for accountability. Peer-to-peer relationships in informal settings are therefore very important in defining and socializing the more hierarchical and formal notions of accountability in an organization.

The mechanisms for this are mimetic: it’s very much about learned behavior. You join the organization and you begin to mimic the people around you in order to fit in. And that's what makes it voluntary. People actually like to fit into social situations.

Peer-to-peer accountability is very much non-dischargeable. This kind of accountability never goes away because it's a living relationship and it will grow and change for as long as the relationships persist.

Accountablity According to Butler

I want to point you in the direction of a book by Judith Butler called, "Giving an Account of Oneself." I have found it to be really intriguing and compelling on the subject of accountability. Judith Butler is a gender theorist. She talks about all kinds of personal relationships, and the notion of accountability that she develops is quite profound.

Judith Butler in 2013 (credit: Wikimedia, public domain)

One of the key things that Butler points out is that we can't actually fully provide an account of ourselves, because it's impossible to express everything about ourselves. We don't understand ourselves fully. We can't explain, for instance, why we wore a certain outfit on a certain day. We can't explain why we decided to take the long way home. We can't really explain anything to a complete and exhaustive level that would fully provide an expression of who we are.

So, because we can't fully express ourselves, it's impossible for accountability ever to be complete.

In addition, we are often embedded in formalized systems of accountability. Butler points out that when you try to provide an account of yourself in any kind of an organization or other formal system, your account is recorded and taken away from you. And it is used in ways that are beyond your control. So it, it it abstracts that account from us. It rips the account away from us in ways that it no longer belongs to us. And it's no longer our own account because it becomes the object of the corporation or of the organization or the legal system that we're in. You know, when you provide a witness statement, for instance, in a legal situation where you saw something happen, you know, that account gets recorded and you never see it again. You may never even know whether you words were taken down as accurately as you wanted, unless you had a chance to review the transcript of your statement and sign off on it. So, you know, these accounts that we provide of what we saw and what we think, and what we believe happened are often just objectified and taken away from us.

Accountablity According to Shearer

Teri Shearer is a scholar at Queens University in Kingston, Ontario, a really wonderful thinker. She used Judith Butler and a couple of other scholars — Lacan, for instance — to talk about the role of accounting in accountability relationships.

One of the things that she focuses on is Lacan’s notion of accountability not being about ourselves, it's actually for the other person in the accountability relationship. We provide accountability for the Other.

In doing this, we're trying to explain to that other person the reasons not just for our conduct, but our character. It’s not just about what we did, but who we are.

The important thing about this kind of accountability, this profound accountability, is that it renders life intelligible and meaningful.

I want to draw attention to the notion of meaning here, because we're going to come back to it later in this lesson. Accountability makes life meaningful.

But the role of accounting, according to Shearer, is problematic in this process. Accounting actually undermines accountability in a lot of ways. To begin with, it constructs us as economic subjects. So, rather than seeing us as full human beings, it reduces us to the economic roles that we play in the economy. It circumscribes us. It takes our humanity and reduces it to the sum of our economic actions.

The other thing accounting does is that it commodifies our accounts. Earlier I talked about Butler’s insight that our accounts are taken away from us. Accounting makes this even worse. Our accounts are turned into a commodity, something that can be traded and assembled by accounting and fed into systems where our accounts are monetized in some way. We see this obviously at a corporate level with accounting information being fed into the stock market, but we also see it at a personal level in social media. The stories that we give of ourselves are commodified and turned into money by Twitter and TikTok and Facebook and every other platform.

Because accounting constructs us as economic subjects, it assumes that we all act out of greed. It assumes the worst of us, that we're all out there trying to get the biggest piece of pie that we can for the least effort. Accounting doesn't even begin to deal with the possibility that we might want to provide an account, that we might want to contribute something to our organization. It assumes we make decisions in order to maximize our own utility, and it measures this behaviour in financial terms. It's an extremely reductionist notion of accountability that's built into our accounting systems.

The Limited Liability Corporation

Let's take these notions of accountability from John Roberts and Judith Butler and Teri Shearer, and start to apply them into the corporate setting. What does it mean to talk about corporate accountability, as opposed to individual accountability?

An incorporated company is what’s called a limited liability corporation. If you want to know about accountability for corporations, the clue is in the name. It's telling us that a corporation is specifically designed to avoid accountability. Corporate liability is limited.

We usually talk about this as applying to shareholders, That when you purchase shares in a corporation, your own assets as a shareholder are exempt from any litigation involving the corporation. If someone sued a corporation and won, and took all the resources that the corporation owned, that would be the end of the lawsuit. They couldn't go after the personal assets of the shareholders. And that's what limited liability primarily means.

But this notion underlies all of our contemporary thinking about corporations. Corporations are organizations that have been set up in many ways to facilitate the avoidance of responsibility, whether it's for pollution or taxation or consumer liability or employee wellbeing.

One problem with corporate accountability is everything's so systematized. The mechanisms of corporate accountability are extremely ritualistic. Auditing, for instance, is this ritual where the auditors show up once a year, they go through a kind of performance of digging into the files and rendering a stylized opinion, a benediction. Auditing is a quasi-religious ritual in that it enacts for everybody this ceremony of accountability.

Corporate accountability is also formulaic because when you're talking about accounting systems, this basic formula, “assets = liabilities + shareholders’ equity,” drives our notions of accountability. If we can account for all of the resources that the corporation had and show where they went, then we have mathematically proven accountability in some way.

Corporate accountability is extremely narrow. Financial accountability is the predominant focus and it gets very disconnected from broader corporate social responsibility. Accountability for environment, accountability for ethics, accountability for governance, accountability for the impact on society: all of that is separated from and made subordinate to financial accountability.

One of the basic problems here, of course, is that financial accountability is such a strong instance of accountability in our society that it's assumed to prove something essential about the corporation, that the corporation is doing something right so long as it has provided audited financial reports. Everything else that happens outside of the world of finance, all the things that are not measurable in dollars or euros, gets separated and relegated to secondary accounts. This puts a primacy on financial accountability, over and above any sort of general accountability.

We can also observe that corporate accountability can become an exercise in deflection. If a corporation is involved in something terrible, a senior manager will often resign, sometimes with a golden parachute.

Other times blame gets dumped on a low-level employee. If you look at a crisis in a hospital or in a mine, for instance, oftentimes it's a low level employee who gets blamed. The organization did everything right but this “rogue employee” did something wrong, something that could not have been anticipated. The employee didn't follow procedures properly, and so they get scapegoated.

This is a disturbingly frequent ploy by corporations, which time and time again attempt to avoid any direct responsibility. A corporation never gets punished, not in any meaningful way. This is a specific feature of capitalism. The tools are available to punish corporations, but they're not applied to the organization. They're applied to the individual.

A Tool: The Accountability Cube

We’ve seen that corporate accountability is highly complex. I want to turn now to a conceptual model that can help us think through some of this complexity and get a handle on what we mean by “corporate accountability.”

The model is called the accountability cube. I came across it in a paper by Brandsma and Schillemans. (Schillemans was one of the authors of the paper on accountability that I mentioned earlier.) They came up with this concept of the accountability cube, and I, along with my co-authors Darlene Himick and Pier-Luc Nappert, developed it further to try to flesh out what we all mean by accountability. We tweaked the original model from Brandsma and Schillemans a bit, in order to bring out some of the ideas on accountability that Roberts, Butler and Shearer have expressed.

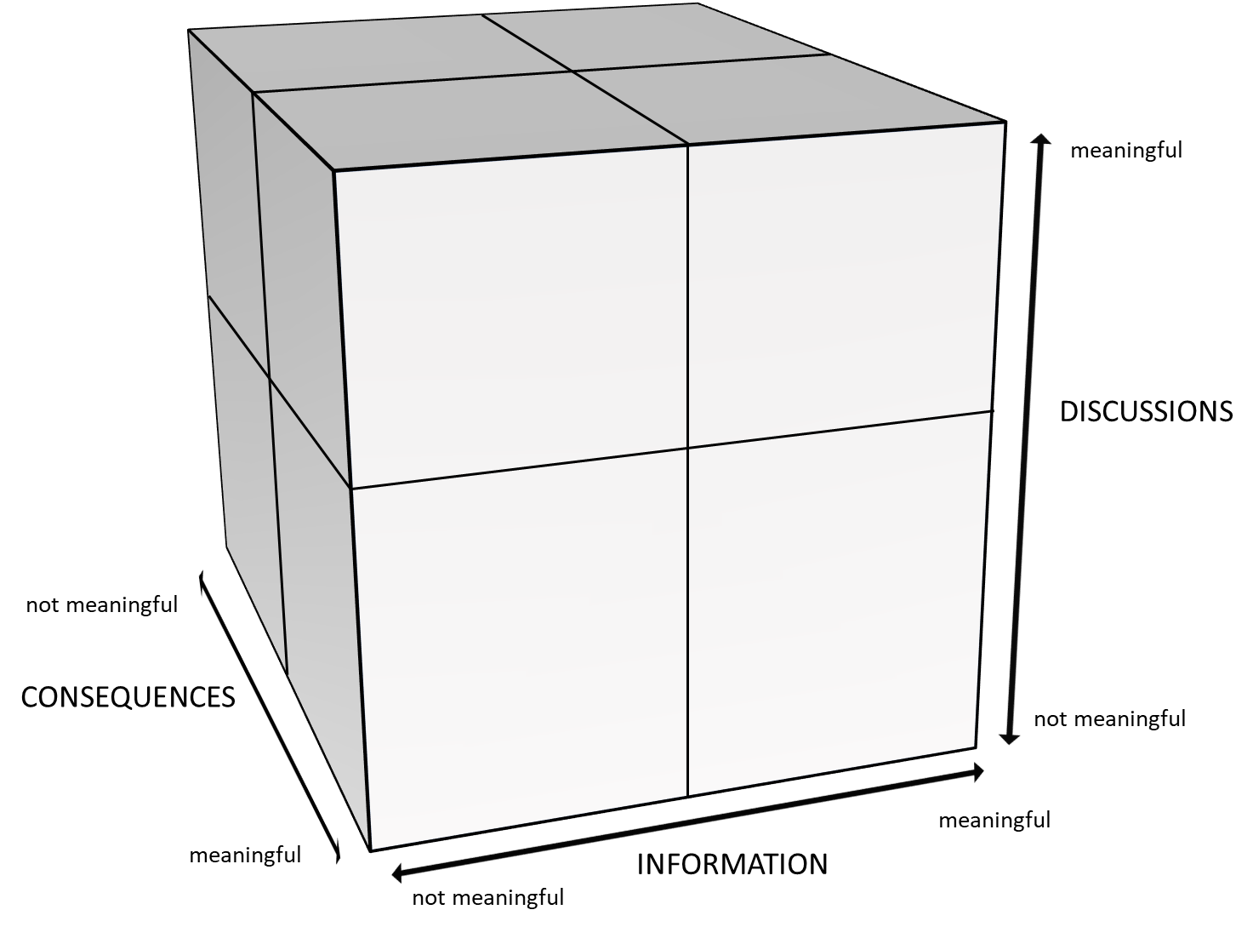

And here is our version of the accountability cube.

You can see it is a 2x2x2. As you know, 2x2 matrices are a standard feature in academic literature. If you can just divide the world into two categories and combine that with two other categories, you can begin to think analytically about what happens in each of the quadrants. In this case it's three-dimensional, so you've got eight possible boxes, or octants, that the world can fit into. And of course, this is still an oversimplification. That's the whole point of an analytical model: to simplify things a little bit so that you can begin to make sense of the world.

This is not to suggest that everything fits cleanly into one of these boxes. It’s just a tool for thinking, and if you were to push the categories even a little bit, you’d realize they are probably better thought of as spectrums rather than binary oppositions. However, what a model like this does is invite us to focus on each of the boxes temporarily, to the exclusion of the others. Doing this helps us understand a little bit more about what we mean by accountability.

Dimensions

So, there are three different dimensions here.

Information

The first dimension across the bottom is the notion of information. If you're going to have accountability, somebody has to provide some information about what happened.

And in this accountability cube, I've described the end points as either being meaningful or meaningless. This goes back to Teri Shearer's comment about accountability being something that helps render the world meaningful. That's why we chosen these category labels of meaningful and not meaningful.

Information helps us create meaning, but there's all kinds of situations where we don't have enough information, or the information that we got is the wrong kind, or it's about stuff that doesn't matter. To the extent that information is meaningful, therefore, you have a greater chance of accountability.

Discussions

The second dimension is on the right-hand side, discussions. If you've got discussions between the people who are providing the information about what happened, and the people that they're accounting to, those discussions might be empty ceremonies, formulaic, nonsensical. If that’s the case, nothing really important happens in them.

Alternatively, they can be deep, probing, engaging conversations about what was going on, a real human-to-human encounter. That would be a meaningful discussion.

To the extent that we can have meaningful discussions about the information that's been provided, then we're going to move further towards achieving accountability.

Consequences

And finally, we have the dimension of consequences. If there are no consequences that arise out of all our efforts to provide meaningful information and have meaningful discussions, we've got very little chance of holding anybody accountable. And if we're the accountable party, we’ve got very little chance to prove our accountability if there's nothing at stake. In order for accountability to happen in any deeper sense, we need to have consequences that are meaningful, be they rewards or punishments.

Consequences have to be meaningful in the context of the specific accountability relationship. For example, in a university course, a meaningful consequence would be that you either pass the course or fail the course. Those are meaningful consequences for what you do in a university course, but they are not particularly meaningful to anybody who's not in the course, right? Whether or not you pass your course or not might not matter at all to your grandmother. She’ll love you anyway. Am I right? This is important to keep in mind, by the way. Grandmothers love you no matter what.

At any rate, the meaningfulness of consequences really depends on the context.

Breaking Down the Cube

If we look at those three dimensions, you can see that the top right corner, where we have meaningful information, meaningful discussions and meaningful consequences: that upper corner is where you'd have the most accountability. Or at least the greatest chance of genuine accountability happening.

At the bottom left corner at the back, where you've got meaningless consequences, meaningless information and meaningless discussions, you're going to have the least accountability. It's very unlikely that any accountability that matters is going to happen under those conditions.

If we look at this cube, we've got eight different boxes we can think about and begin to play with, to see the ways in which these dimensions work together to create accountability. Doing this systematically gives us the following table, where dimension is a column and every possible combination of the attributes “meaningful” and “not meaningful” can be listed.

I've put a check mark to indicate “meaningful” and an x to indicate “not meaningful.”

Three Check Marks

Across the top, then, where you've got meaningful information, meaningful discussions, and meaningful consequences, that corresponds to the top right corner in the cube. Everything is happening optimally and you've got the greatest chance of accountability, so I’ve labelled that accountability.

Two Check Marks

Now what happens if one of those attributes is missing, so you’ve only got two check marks?

If you've got meaningful information being provided and meaningful discussions, but there's no meaningful consequences, what could we call that situation? I've labeled it ritualism. The idea here is that we just go through this ceremony of providing accurate, helpful information, and we have this great discussion about it, but nothing comes of it. Nothing happens next. This is a performance of accountability without any consequences to anybody.

The next line is where you've got meaningful information and meaningful consequences, but nobody had a chance to discuss it. It's like you give this account to somebody and they run off with it and decide what to do about it, but you don't even get a chance to sit down and talk with them about it. I've called this autocracy. You can imagine a surveillance state where there's a lot of information being recorded about the citizens, say through CCTV footage, and the consequences can be quite severe for people, but they don't get a chance to defend themselves in court. That's why I've called this autocracy.

The next line is where you've got no meaningful information, but you've got meaningful discussions and meaningful consequences. The discussions and consequences are not based on any meaningful information, so I've labeled that as guesswork.

One Check Mark

Now let's step back even further and consider situations where two of the attributes are missing and only one of them is present.

If you've got no meaningful information available and there's no meaningful discussions taking place, but there are meaningful consequences for people, I've labeled that as a witch-hunt. You can think of the archetypal situation of the witch hunts in Salem, Massachusetts, where there were farcical trials: "Burn the witch!" The consequences were very severe; women would die as a result of these trials. However, the information that was being used was completely meaningless. It was not based on anything but misogyny and unfounded accusations. That's why I think the word witch-hunt captures this particular combination of attributes.

The next line is where you've got no meaningful information or consequences, but where discussions are very meaningful, even intense. But they are intense discussions about nothing in particular. What do we call that? I call it gossip. Gossip is perhaps not a perfect label for this because, of course, gossip sometimes does have consequences for people. It can be quite harmful. But in the sense of idle gossip where people chat about what’s going on in town and it’s fairly benign, such discussions can be more about the participants building their own relationship than about the person or events they were talking about. In such a case, there will be very little in the way of consequences for anyone they talk about, so that's why I've called it gossip.

The next line is where you've got meaningful information, but there are no meaningful discussions or consequences. What could we call that? I've chosen the word hobby. Think about birdwatching, where people just look for birds for the sheer pleasure of the experience. They document all the birds they see, keeping a log book for their own use, simply out of something to do for fun. It's just a hobby, as opposed to the work of, say, a biologist studying ecosystems.

No Check Marks

The final layer of course, is where you've got no meaningful information, no meaningful discussions and no meaningful consequences. I’ve called that laissez-faire. If anybody can get away with anything and there's no consequences, nobody cares what happens, nobody tries to talk about what happened in order to improve the situation, it’s just every person for themselves: that's laissez-faire.

I urge you to keep this table in mind as we work through the course together. Try to apply this to situations you hear about on the news, or that you observe at work. Who is actually being held accountable by the report that you’re reading or hearing at? Is the information meaningful? Are there any processes for dialog? Are their any consequences, and do they matter? What would it mean to have accountability in this situation, and what might be missing?

By using this cube, we can think about the ways in which the very purpose of accounting is not fulfilled.

Summary

To wrap up, let’s review what we've covered in this lesson.

We talked about accountability theory. We looked at some common sense definitions and some basic accounting research definitions. Then we looked at some of the common assumptions underlying these definitions: the way that we often think of accountability as binary, hierarchical, involuntary, and dischargeable — meaning that if you provide an account that’s full and complete, then you're done, you have no further obligation.

We then looked at complex accountability situations, particularly social and organizational accountability that goes beyond the simple settings where one worker is responsible to a manager.

We reviewed the work of a few interesting accountability theorists, including John Roberts, Judith Butler — who talked about the difficulty in giving an account of yourself because you can't fully understand yourself, and often the account that you do provide gets taken away from you so that it's no longer your account of who you are — and finally Teri Shearer, who talked about the role of accounting in accountability and described how accounting commodifies the accounts that we provide and makes it almost impossible, in some ways, for true accountability to happen.

Next we looked at corporate accountability and recognized that corporations, by design, provide limited liability.

And finally I introduced you to the accountability cube, with its dimensions of information, discussions and consequences.

So that's the lesson on accountability. I hope that you found it meaningful!

In our next lesson, we get back to the nuts and bolts of accounting.

References

Brandsma, G. J., & Schillemans, T. (2013). The accountability cube: Measuring accountability. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 23(4), 953-975.

Butler, J. (2005). Giving an Account of Oneself. Fordham University Press.

Foucault, M. (1980). Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews & Other Writings. Pantheon.

Bovens, M., Schillemans, T., & Goodin, R. E. (2014). Public Accountability. In M. Bovens, T. Schillemans, & R. E. Goodin (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Public Accountability (pp. 1-22). Oxford University Press.

Roberts, J. (1991). The possibilities of accountability. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 16(4), 355-368.

Shearer, T. (2002). Ethics and accountability: from the for-itself to the for-the-other. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 27(6), 541-573.

Graham, C., Himick, D., & Nappert, P.-L. (2023). The dissipation of corporate accountability: Deaths of the elderly in for-profit care homes during the coronavirus pandemic. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 102595.

Title image: Detail from Michelangelo’s Last Judgement. It’s just a dramatization of accountability. Individual experiences may vary. (Credit: Image is in the public domain.)