What's in a definition? When we come up with a definition for something, what do we think we are actually doing?

For the sake of argument, let's look at the Oxford English Dictionary, and ask it to define "definition." (It's this kind of circularity that makes philosophers go crazy.)

The OED say this:

definition

Pronunciation: /dɛfɪˈnɪʃ(ə)n/

NOUN

1 A statement of the exact meaning of a word, especially in a dictionary: "a dictionary definition of the verb"

This doesn't cover everything, because often when we wrestle with definitions, we are dealing with how words are actually used, not how some authority things they should be. In such cases, a dictionary is no help at all. For this reason, the OED goes on to provide a sub-definition:

1.1 An exact statement or description of the nature, scope, or meaning of something: "our definition of what constitutes poetry"

As with the main definition of "definition," this one uses the word "exact." This word, I think, captures quite succinctly the desire behind a dictionary -- the desire not just for precision but for a resolution, an answer. This is the desire that leads people to become dictionary editors, and the rest of us to become dictionary users.

The sub-definition begins to acknowledge, however, that our desire for linguistic precision will always be partly unfulfilled. The phrase "nature, scope or meaning" suggests that "definition" has multiple uses. These uses might not always be compatible, leading to multiple definitions for a word. And the choice of poetry" as an example suggests that we sometimes have to talk about things that resist definition, where definition is difficult and even contentious. What is poetry, after all?

Most would agree that Shakespeare's sonnets, for instance, are poetry, but does it still count as poetry when a poem doesn't rhyme? For most people, the answer is yes. We call it blank verse and it is extremely common.

What about if the lines don't scan, though? What if they don't have a recognizable metre? Again, most people today would say yes. We call it free verse.

Does this mean that we can randomly throw words together and call them poetry? I'm guessing that most people would say no. Certainly, many poets have said no. Free verse is only free from the conventions of metre, they argue, but it still needs to somehow play with rhythm and rhyme and the meaning of words and so forth, and conform to other more subtle conventions, if it is to be recognized as poetry.

Behind our attempts to define, once and for all, what counts as poetry, lurks a trap. This trap has to do with the commonplace assumption that there is something at the core of our concept of poetry, some intrinsic quality that, if we could just put our finger on it, would lead everyone to agree that yes, that is what poetry is. We would have put our finger on an objective definition of poetry.

The idea here is that there is poetry out there in the world, and that a good definition would capture the essence of that poetry. It would settle once and for all what is poetry and what isn't.

This is unlikely to happen for something as slippery and various as poetry. It's not even likely to happen for something as simple as an apple. When we make statements such as "a poem is a collection of statements that plays with rhythm, cadence, diction, meaning and sometimes rhyme" or "an apple is a red fruit with white flesh and seeds inside," we are often guilty of trying to capture something intrinsic about these things. We regularly fail: some apples are green, for example.

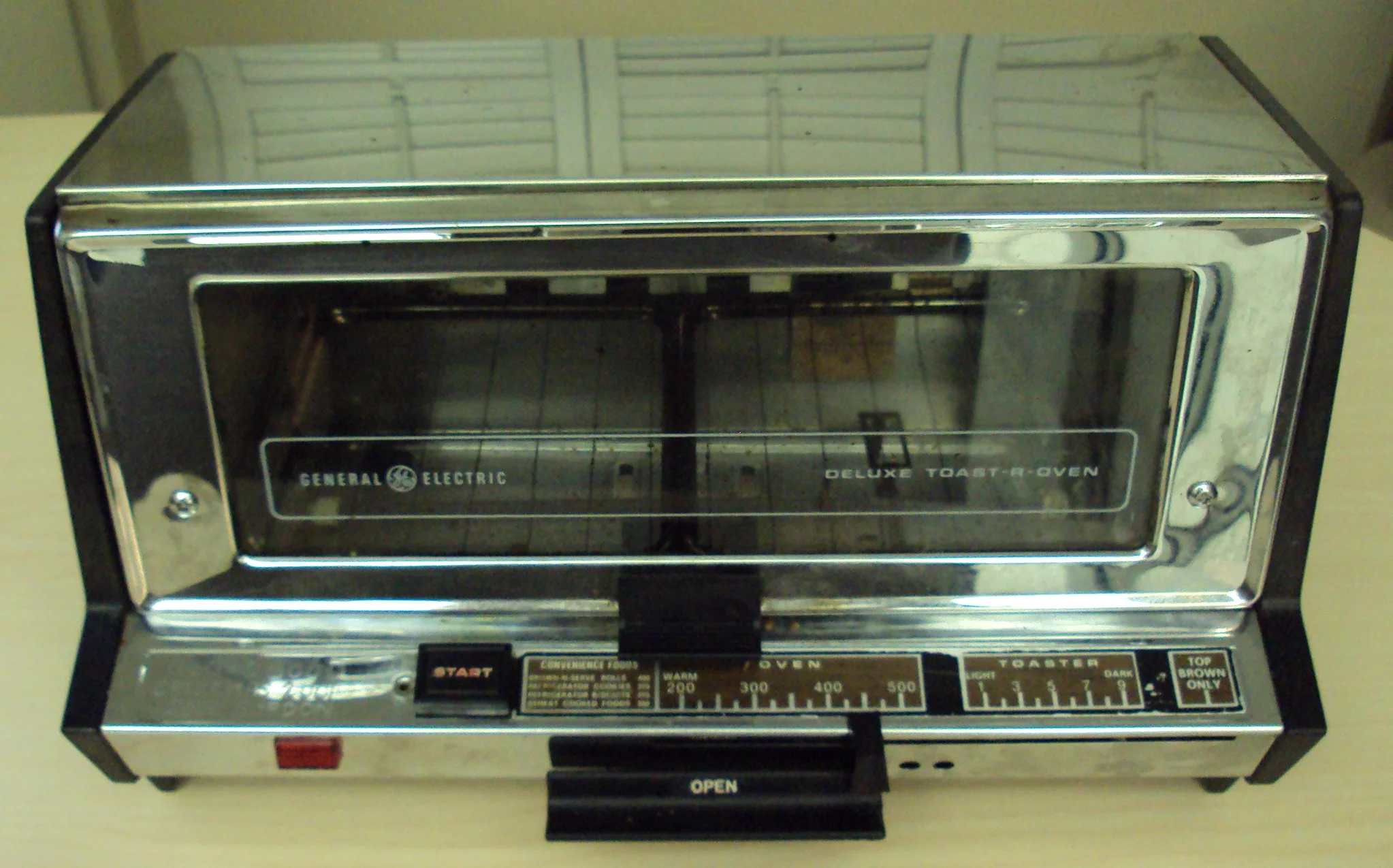

Philosopher Richard Rorty argued that this way of using language is doomed to failure. Things, he said, don't have intrinsic qualities. They only have qualities when they are brought by us into relation to other things. A particular apple is an apple because it is like other apples and it is not like an orange. A poem is a poem because it is like The Waste Land or a Shakespearean sonnet and not like a user's guide to a toaster oven.

Rorty famously used the example of the number 17. There is nothing seventeenish that we can point to when we talk about the number seventeen. It has no essence. It is only 17 because it is one more than 16 and one less than 18.

Thinking of definitions and descriptions as somehow capturing the essential or intrinsic qualities of something is not very helpful. It doesn't get us anywhere.

What then, is a more useful way to think about definitions? I would argue, and indeed I have argued this in my research, that the way to proceed is to adopt what Richard Rorty calls an "anti-essentialist" approach to definitions. An anti-essentialist definition doesn't presume that there is an essence to anything, any intrinsic qualities that we can all agree on. Instead, it defines things in terms of a loose set of attributes that we generally agree pertain to the thing we are trying to define, but we aren't too fussed about any one attribute. As long as an object has enough of the attributes for us to recognize it as an example of our definition, we're happy. And if we're not sure, we don't throw up our arms and quit. We just say, "Well, our definition wasn't good enough. Let's try to improve it."

Think of a definition as a web of attributes, like a big basket woven out of nylon straps that have to be able to bear the weight of the thing we are trying to define. Imagine that the straps aren't woven in an orderly fashion, but are just woven together randomly until we have a big messy basket that can hold something. Suppose we're trying to define something big and heavy, like "car," and we've woven together a robust definition that is big enough and strong enough to hold the weight of "car." We've got this "car" idea hoisted up off the ground in our strapping young basket, and it's looking mighty fine up there. We're awfully proud of our definition because it's holding so much weight.

Our definition would probably have straps that say "Cars have bodies" and "Cars have engines" and "Cars have windows." It might have hundreds and hundreds of straps that all pertain what we think of when we think of cars.

Now imagine that we relax the definition a bit. Suppose we cut the strap that says "Cars travel." Would the definition still hold? Sure it would. Think of a car that's in the shop waiting to be repaired. Even though it's not working properly at the moment, It's still a car.

What about "Cars have wheels"? If we cut that strap, would the definition still hold? I think so. Think about a car sitting in someone's backyard, sitting up on blocks and rusting away. It's still a car. Not a very good one, but it's still a car.

If we keep cutting straps on our definition, cutting, cutting, cutting, then eventually the definition we used to hoist the idea of "car" up off the ground just gives way, and the "car" comes crashing down. At this point, our definition of car no longer works.

But which of the straps that we cut caused the problem? Was it the last one? What if we'd cut them in a different order? Would the idea of "car" have crashed to the ground sooner or would it still be up there?

It's clear that some straps in our definition may be more important to use than others. They may hold more of the weight, so to speak. But there isn't a single strap that couldn't be cut without us being able to imagine that somehow the definition still holds. Gas engine? No problem, it could be diesel. Roof? No problem, it could be a convertible. No engine at all? Well, that's stretching things, but if your car is sitting in the shop with the engine removed, it's still a car for the purposes of a repair shop.

This is important. "For the purposes of a repair shop." Definitions are just our agreed understanding of words, and the usefulness of them depends on the purposes we have in mind for them.

Rorty argues that words are just tools. We use them because we are trying to accomplish something, to control an outcome. Understanding definitions of words, therefore, requires that we look at the social factors that caused us to define something the way we did.

Words, in other words, are about power. Embedded in any definition are a set of interests. Whose interests are served by defining something in a given way? How would those interests be harmed if the definition changed?

This gives us a completely different way to think about the world than pretending that there is an intrinsic or essential quality behind things that we should try to pin down. Things don't have essences, Rorty argues, but the way we talk about them definitely matters.

Photo of a statue at the Musée D'Orsay taken in 2012.

Photos of toaster oven taken in 2012.