In my previous post, I introduced the notion of microaccountability, the way that formal accountability is diffused into the informal daily interactions of one person with another, transforming these interactions into a system of mutual surveillance and self-monitoring that harnesses people to global capital.

My co-authors, Chandana Alawattage and Danture Wickramsinghe, and I developed this concept from our study of microfinance in Sri Lanka. We conducted fieldwork in three villages there that have been subjected to development through microfinance. Chandana and Danture have a deep network of local contacts in this region.

Our interest in the topic was sparked by visits to the villages in 2012, which is when many of our photos were taken. When I was visiting Danture at the University of Glasgow, we developed plans with Chandana to do a proper investigation of how microfinance was playing out in Sri Lanka. We had read a lot of the critical research into NGO-led microfinance in Bangladesh and Nepal, by Katharine Rankin in particular. We wanted to know what might be different in Sri Lanka, where microfinance was being conducted for profit by commercial banks instead of NGOs. And being accounting scholars, we wanted to know how accounting and accountability operated in microfinance.

Conducting the Research

The first phase of our research took place during visits by Danture and Chandana to Sri Lanka in 2013 and 2014. (Danture lives in Glasgow, Chandana in Aberdeen. Such is the global nature of academia.) We conducted 71 hours of initial fieldwork, including interviews with 49 people. We talked to officers of the central and regional bank, to bank employees working in the villages, to the women who were the actual “microborrowers,” to their family members, and just to get another perspective, to one local academic. We also drew on a large number of secondary sources available in the public domain, and a comprehensive set of documents and forms obtained directly from the microfinance institutions.

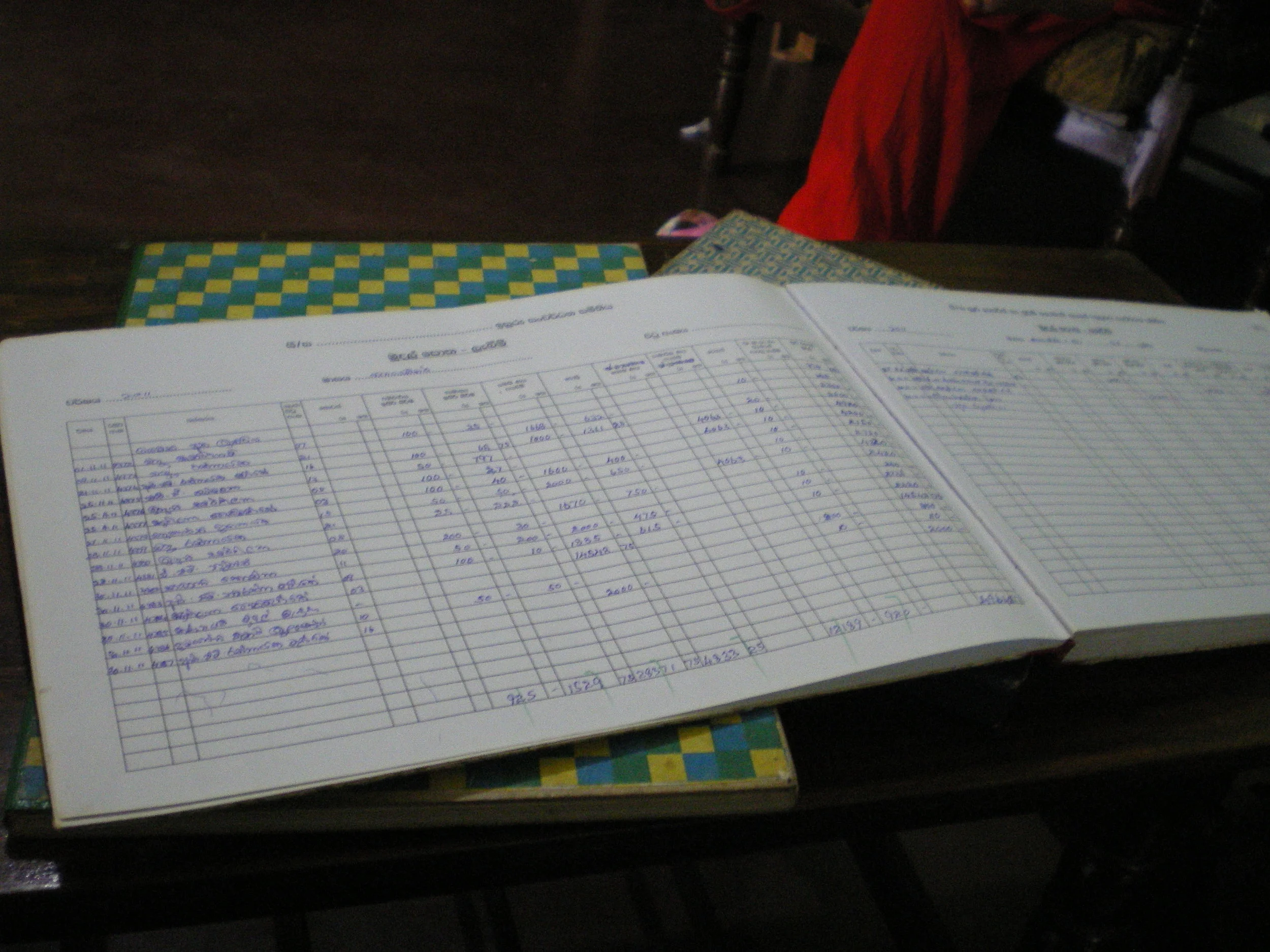

One of the microfinance forms we collected

We also attended nine small group meetings and made six visits to the women’s microbusinesses. While our visits covered three villages, in our academic paper we highlighted the village of Parakatawella, to make our story more concrete. I do the same thing here, for consistency.

In 2016 and 2017 we returned to Parakatawella for a second phase of fieldwork, on the advice of our journal reviewers. We conducted additional interviews with women from one microborrowing group, so we could focus our paper more closely on the lives and experiences of these women. We followed up our visits with many Skype calls to clarify details.

I will take you through what we learned, but I want to start by describing how finance operated within these villages before the microfinance industry arrived.

Traditional Practices

Traditional financial practices were confined to arrangements amongst the villagers themselves, with no recourse to the formal banking sector outside the village. The most prominent form of saving, lending, and borrowing was called the ciettu system. It involved a dozen villagers getting together to pool their savings. This allowed each ciettu to run for a calendar year. Each member contributed a specific but equal monthly amount (say Rs 2000, about $15) to a monthly cash pot. This entire monthly pot would be available to one group member to use for various socially acceptable needs, such as paying for a family wedding or buying schoolbooks.

There were two different ways of selecting who would get the monthly pot of cash. A “draw ciettu” was decided by a random draw, although special circumstances like an upcoming wedding might be taken into account. This was more popular among women. An “auction ciettu” put the monthly pot up for bid, and was more popular among men.

The ciettu system for pooling money paralleled the traditional system for pooling women’s labour. Women would gather in groups of 10 or more to do things like planting a woman’s rice paddy or making clothing. They would work together, sing together, eat together, knowing that their gift of labour would be returned in time. These are the rhythms of comradery and teamwork that have been disrupted and repurposed by microfinance.

Village dog visiting the microborrowing group meeting

In addition to the ciettu for saving, there was a traditional system of lending. Wealthier villagers offered personal loans to those in need of emergency cash, often at a very high interest rate, similar to the rates now charged by microfinance banks. (In fact, the banks themselves make this comparison to justify their high interest rates. They never compare their microfinance rates to the much lower rates they charge established businesses in Sri Lanka.) Because of the high interest rate and the sometimes coercive means employed to recover such loans, these traditional lending arrangements were a last resort for villagers in need of cash.

In the next few posts, I’ll describe how Sri Lankan microfinance banks have actively transformed these informal practices, in order to earn profits from rural villagers who previously had never used banks.

Photos © 2012-2013 Wickramasinghe. (I mistakenly dated the photos as 2007 when this was first posted, having misread the timestamp information.)

Our Article

Alawattage, C., Graham, C., & Wickramasinghe, D. (2018). Microaccountability and biopolitics: Microfinance in a Sri Lankan village. Accounting, Organizations and Society.

Further Reading

Rankin, K. N. (2001). Governing development: neoliberalism, microcredit, and rational economic woman. Economy and Society, 30(1), 18-37.

Rankin, K. N. (2002). Social capital, microfinance, and the politics of development. Feminist Economics, 8(1), 1-24.