I had planned to jump into a real-life example of cash flow statement shenanigans, and I will, but the example I have in mind depends on one other accounting concept, corporate income tax.

So, here is the 30,000 foot (9144 m, for you kids) view of why corporations don't pay as much tax as you'd think, or perhaps should.

There are three reasons: the corporate tax rate itself, tax arbitrage, and carry-forwards.

The Corporate Tax Rate

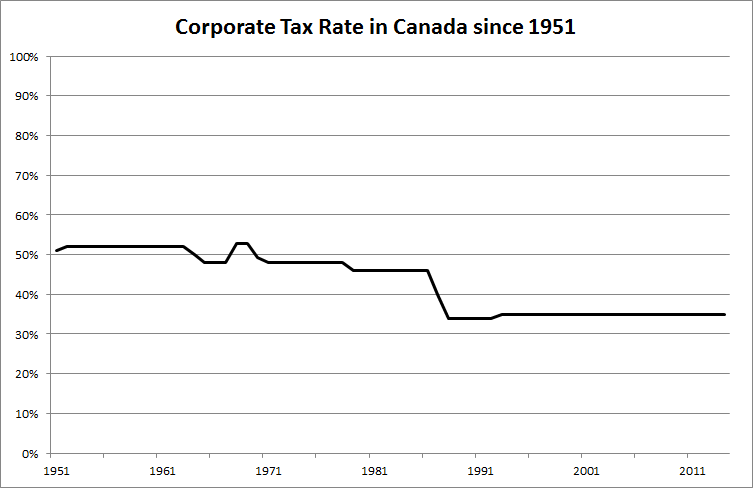

Corporate income tax rates in Canada are low now, compared to thirty or forty years ago:

This chart shows that our tax rate for corporations is currently 35%, and has been at about that level since the late 1980s. Back in the 1950s, however, when Canada was building its social welfare programs for healthcare and income protection, the corporate tax rate was over 50%. So, to people my age, the current corporate tax rate seems low.

However, it used to be even lower:

This is the same chart, extended back to 1910. It shows that prior to World War I, the corporate tax rate in Canada was only 1%. The federal government at that time relied mainly on excise taxes and import duties for its revenues.

After WWI, corporate tax rates were raised to over 10% to help pay for the war. This was also when personal income tax was introduced, for the same reason.

World War II led to the next big jump in tax rates, which were raised to about 40% to pay for that war. Then they were raised again in the 1950s and 1960s, when Canada created its much envied public healthcare, public education, unemployment insurance, and welfare systems.

Income taxation at present levels is thus the result of a massive rise in our expectations about what governments should do: wage massive wars, provide massive socioeconomic benefits.

But then in the 1980s, corporate tax rates were lowered. This had to do with the election of a federal government that preferred markets over bureaucracies.

Tax Arbitrage

The drop in the corporate tax rate in the 1980s, from around 50% to 35%, was part of the neoliberal (market-based) reformation of government begun by the Progressive Conservative government under Brian Mulroney and continued to varying degrees by Liberal and Conservative governments ever since. Canada mimicked the market-based changes in social and economic policy enacted in the UK under Thatcher and in the US under Reagan.

While the social policy changes affected individual Canadians directly than the economic changes, for the purposes of this article I want to focus on the lowering of corporate tax rates.

Part of the logic behind this was that lowering corporate tax rates was expected stimulate Canadian corporations to increase their economic activities, because those activities would produce more net income. But Canada was not operating in isolation.

As I have discussed previously, Ireland lowered its corporate tax rates dramatically in the 1990s, creating jobs in its technology sector. Ireland became known briefly as the Celtic Tiger for the apparent robustness of its economy. The tiger's stripes have since faded, due to what is called tax arbitrage.

Arbitrage is when someone takes advantage of differences in prices between two markets. If the bread sells for $1.00 a loaf in Toronto and $2.00 a loaf in Montreal, anyone with a car can buy bread in Toronto and sell it in Montreal for a profit. If the cost of the car and gasoline don't eat up too much of this profit, you'll come out ahead.

If a corporation can make cars in Detroit by paying workers $58 per hour in wages and benefits, and can make them in Mexico by paying workers $8 per hour, guess where production is moving?

The same concept applies to taxation. If the corporate tax rate is 35% in Canada and 5% in Ireland, a Canadian corporation can move its operations to Ireland and save money, all else (like wages) being equal.

This is a race to the bottom, where countries compete with each other to offer the lowest tax rate. The problem is compounded, though, because a transnational corporation like Apple, as we have seen, doesn't actually have to move its production to another country in order to take advantage of the lower tax rate. It can just set up a shell company in that country and transfer some profits to it. The company as a whole will pay little or no taxes on that profit, lowering its overall tax bill.

Ireland, corporate tax heaven.

Carry-Forwards

Tax arbitrage isn't just a geographical phenomenon. It's also a temporal one. What do I mean by that? Let me explain.

Tax accounting for corporations differs fundamentally from personal income tax. If you as an individual earn a salary in a given year, you are taxed on that salary. You do have access to certain tax deductions, such as charitable donations, and tax credits for having children. These vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. However, one thing remains constant: your wages in a given year are taxable in that year.

Corporations are taxed year-to-year in a very different manner. First, they are only taxed on their net income (revenue minus expenses), not on their gross income (revenue). Imagine a world in which you were taxed not on your salary, but on the amount of money you had left after paying your living expenses. That's the world corporations live in.

Now imagine that if your living expenses exceeded your salary this year, you could carry that loss forward onto next year's tax return, and reduce any taxable surplus you might have then. Sounds lovely.

Now imagine you could continue doing this for 10 or more years, until a big loss from one year is finally used up in others. Only then would you again have to pay income tax. Lovelier still.

And now imagine that you could not only carry this year's loss forward, but you could use it to apply for a refund of any income tax you paid last year. And the year before that. And the year before that. That's the world corporations live in.**

Let me illustrate ...

Suppose a small business, organized as a private corporation, has been earning $50,000 in taxable income per year. Let's compare that to an individual, working as an employee, earning the same amount of taxable income in wages. In Canada, both the private corporation and the individual will be taxed at roughly the same overall federal tax rate, around 11% or 12%. Let's say 12%, because that means both will have been paying a nice round $6000 in taxes. (I'm ignoring provincial taxes for the moment, for simplicity. All they would do is increase the tax rate we are using. Nothing else would change.)

Now, let's imagine that this year there is a severe economic downturn. For both the small business and the employee, the cash coming in falters:

The corporation's revenues drop, leaving it with a tax loss (negative taxable income) of $20,000. It will pay no taxes this year.

The individual employee, meanwhile, suffers the same loss. Her income drops to the point where she is $20,000 short of the point where she would have paid taxes. She also, therefore, will pay no taxes this year.

The difference really kicks in next year, when the economy returns to normal. The corporation and the individual will both resume earning $50,000 in taxable income. The individual will once again pay $6000 in income tax. The corporation will not. It will carry forward its $20,000 tax loss from the previous year, leaving it with only $30,000 of taxable income. This means it will only pay $3600 in taxes. Only in the following year will it resume paying its full $6000 in taxes.

Next Up

Taken together, the competition between countries to have the lowest corporate tax rates and the tax carry-forward calculations that corporations enjoy have had a major effect on national tax revenues around the world. In my next article, I will show how this has affected Canada.

And then I should be able to return to the question of cash flow shenanigans, armed with our new understanding of how corporate tax works.

* I have been unable to find a similar table of historical personal income tax rates, to match the corporate ones shown here, but my sense is that personal income tax rates followed roughly the same trajectory.

** Wealthier Canadians who make investments in the stock markets can carry forward their losses on bad investments, and use them to offset gains on good investments. They can't use them to offset income from wages, though.

List of historical tax rates obtained from the Tax Policy Center. The graph is my own.

Photo of Toronto's waterfront taken in 2016 from the offices of Canada's largest corporate law firm.

Photo of Carraig Phádraig in Ireland taken in 2013.