This lesson is all about accounts receivable, the money owed to a company by its customers. The key issue here has to do with the accounting principle of conservatism: the general notion that financial statements shouldn’t overstate things. In this case, the problem is that it is likely that at least some of the customers, for one reason or another, will not pay their bills. How does a company take this problem of “bad debts” into account if it is going to be conservative in representing how much money it is owed by its customers?

First, we're going to explore the general topic of receivables and bad debts. Then we're going to look at two accounting methods used to deal with the expectation of bad debts: the ageing of receivables method and the percentage of credit sales method.

Receivables and Bad Debts

Accounts receivable, or A/R, are generally speaking the amounts owed to a company that it expects to receive sometime soon. It’s the short time horizon that distinguishes A/R from, for instance, a loan made by the company, which would be expected to result in positive cash flows over the long term.

Accounts receivable could include amounts owed by just about anybody, but typically when we talk about A/R, we're referring to the amounts owed by customers who bought goods or services from the company on credit. That’s our focus in this lesson.

Now, why would a company offer credit to its customers in the first place?

The most obvious reason is to increase revenue. You know what it's like when you see those "buy now, pay later" terms: you can end up buying stuff that you can't afford. That may be a problem for you, but it's great for the company you bought from because they earned revenue that they wouldn't have otherwise got.

A second reason would be more defensive, simply to match what other vendors in the industry are doing. A company may have to offer credit just to be perceived as a legitimate vendor, when business customers in the market expect to be able to pick up supplies as needed and settle their account once a month.

A third reason offered by many textbooks is that companies offer credit to earn interest income. Frankly, I don't think that's much of a factor these days. Unless a company is cash rich and doesn’t have to borrow itself to remain liquid, any interest it earns would be largely offset by interest that it has to pay on its own borrowings, and it would have incurred credit risk (the risk of not getting paid) for little gain. Also, if you are buying something on credit you'll often see that the credit application is for an entirely different company. Your vendor has contracted with a finance company to provide credit to you and its other customers. The credit risk is taken by the finance company and your vendor is getting paid a commission for this. That is not the same as interest income, but the arrangement can help entice sales from customers, and the vendor doesn't have to worry about managing credit at all.

Whatever the reasons for a company offering credit to its customers, what it ends up with is called accounts receivable, an intangible asset, namely the right to receive payments from those specific customers.

Accounts receivable is typically a current asset, so the financial impact of deferring the receipt of payments is not considered material. The amounts owed are accounted for at face value, at least in regard to the delay. (They are not accounted for at face value when it comes to credit risk, as we’ll see.)

It’s quite possible in some industries that a company might have long-term receivables. In such a case, the company would need to use a fairly complicated valuation models to assess the net present value of the delayed payments. That's beyond the scope of this lesson, though, so here we're only talking about accounts receivable as a current asset.

Cash vs Credit

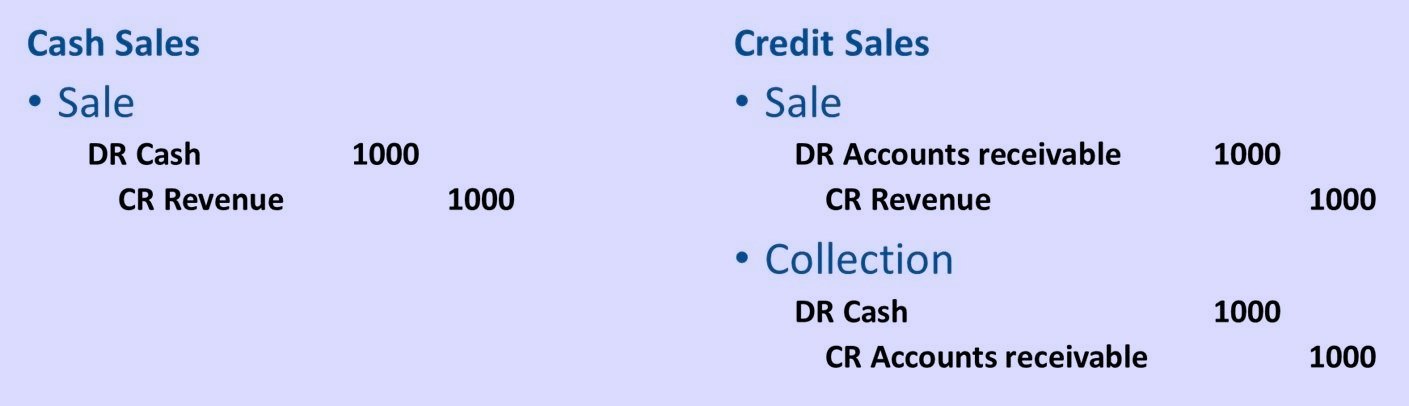

Let's compare two basic scenarios:

On the left you've got the cash sales scenario, on the right the credit sales scenario. With cash sales, everything is straightforward. The customer pays you cash, $1,000 in this case, and we’ll assume for the sake of simplicity that this is recognized right away as revenue. The debit and credit balance each other. The receipt of cash increases the current asset section of the balance sheet, therefore increasing the asset side of the balance sheet. The revenue increases net income, which increases the retained earnings figure in the equity section of the balance sheet. With the assets and equity going up by the same amount, your balance sheet remains in balance.

With credit sales, there is a delay between the sale and the collection of cash. At the time of sale, you still recognize the revenue as you did in the cash scenario, because you've sold something. However, you haven't received cash yet. What you have received instead is an intangible asset, the right to collect $1,000 from the customer. That is classified as a current asset because, we’ll assume, you are expecting to collect it soon, if not during the current fiscal period, at least well before the end of the next fiscal period. Most companies’ receivables are collected within about 30 days, so as well within time period that is considered “current.”

While it’s definitely considered a current asset, the collection is still a event separate from the sale, so it has its own transaction. When the customer pays you the amount they owe, you're going to wipe out the receivable amount you set up at the time of the sale, with a credit to accounts receivable. The offsetting side of this transaction is a debit to cash, of course. What you end up with, when the dust settles, is the same result as the cash sale scenario on the left: a debit to cash and a credit to revenue, but you have coped nicely with the intervening time period between the day the customer received their goods or services and the day they paid.

Accounting for Bad Debts

If you've got an accounts receivable asset, you've got two issues that you need to think about, because things are not always as simple as we just described. The first issue is, how do you handle bad debts? That's what we call it when a customer doesn't pay you. At some point in time, you will give up on the customer and decide that they are never going to pay you. What are the appropriate bookkeeping entries to acknowledge this decision?

The second issue has to do with admitting to the outside world that you are having doubts about collecting from some of your customers. If there is an unusual delay in a customer paying, eventually you’ll start to worry that they might not pay at all. We refer to this problem as “doubtful accounts.” Sometimes your doubts turn out to be accurate and the customer doesn’t pay. Sometimes your doubts are unfounded and the customer surprises you by paying, albeit later than you had hoped. Inevitably, though, you’ll find out that you can't collect every penny from every customer, and it’s not appropriate to pretend otherwise when stating the value of your accounts receivable on the balance sheet.

Direct Write-off Method

Let's deal with the first issue. I'm going to show the direct write-off method for recording bad debts. It’s the most basic method for handling bad debts from customers, and it is so simple that it's really only useful to companies that have negligible bad debt expenses. If you hardly ever sell on credit or you are fortunate to sell on credit to customers who always pay you, then this method might be appropriate.

Let's see how it works. Imagine you've got a customer who can't pay the $1,000 they owe your company. You've investigated the situation by calling them and talking to them, and you have reached the decision that they're never going to pay their debt, and they are also not going to return the goods you sold them. You're simply not going to get paid. What do you do?

Well, the direct write off method involves first of all eliminating, or “writing off,” the accounts receivable that you set up at the time of sale. When you sold the goods (or services) to the customer, you recorded a debit to accounts receivable and a credit to revenue. Now you have to write off that accounts receivable with a credit to A/R, but where does the debit go?

One possibility would be to put the debit back against revenue and simply reduce the revenue you have recorded. Remember, though, that you've already recorded the cost of goods sold or the cost of services that you incurred to make the sale to the customer. Simply reducing your revenue is going to misrepresent your gross margin, which is not particularly helpful to you if you are expecting to use your accounting information to understand your business.

What you do then, under the direct write-off method, is you record a debit to an account called bad debts expense. That’s a separate expense category. By doing this, you maintain a full record of all the sales, as well as a full and separate record of all the bad debts. This will gives you the information you need to manage your credit policies. You may decide in the future, after examining this information, that you're going to reduce credit risk by selling to only certain kinds of customers, or by only offering credit in certain circumstances.

The bad debts information is valuable as a management tool, so that's why bad debts are recorded this way instead of simply debiting revenue. There are however problems with the direct write-off method.

The first problem is a balance sheet problem. Prior to the decision to write-off the debt, the accounts receivable value on the balance sheet was overstated because it included $1,000 that you already knew you were unlikely to collect. When you first created the accounts receivable, it seemed reasonable to expect that you were going to collect the money, but as time went by, your certainty about collection went down and down and down, and the accounts receivable shown on your balance sheet became an overstatement of the amount you were likely to collect.

The second problem is an income statement problem. One of the basic income recognition principles in accrual accounting is that you should match to your revenue all the expenses related to earning that revenue. That is, you should record them in the same fiscal period. Now, if you've got credit sales towards the end of one fiscal period, but you don’t make the decision to write off the customer’s debt until the next fiscal period, under the direct write-off method you're going to have an expense recorded in the wrong fiscal period. The bad debts expense is going to be recognized in a different fiscal period than the one when you recognized the revenue it was related to. That effectively messes up two consecutive fiscal periods, right? In the first fiscal period, net income will be overstated because you haven't matched all the expenses to the revenue, while in the second fiscal period, net income will be understated because you've got extra expenses in there that were not related to that period’s revenue.

We need to find ways to address both of these problems.

Allowance Method

The solution to both these problems is to set up an allowance for doubtful accounts. The allowance for doubtful accounts is an estimate of future bad debts based on the amounts owed by customers for sales that have already taken place. It’s not about possible bad debts related to future sales.

The allowance for doubtful accounts is set up as a contra account to accounts receivable. What this means is that the amount shown on the balance sheet for accounts receivable is actually the net of the gross amount of accounts receivable (a debit balance) and the allowance for doubtful accounts (usually a credit balance — we’ll see later why it might sometimes have a debit balance).

Setting up the allowance as a contra account neatly solves the problem of the accounts receivable being overstated. Using up that allowance later, when the decision to write off a bad debt is made, neatly solves the matching problem, because the bad debts expense is recorded in the same period as the revenue event, while the writing off of the bad debt is recorded without affecting the income statement.

In fact, when the decision to write-off the bad debt is made, there's no visible effect on the financial statements! Let's see how it works.

The general method is fairly straightforward. First, you recognize the expense in the same period as the revenue by estimating it. Let’s say our estimate is $150. How to calculate the estimate is something that we'll cover in a minute, but setting that aside, the journal entry for recognizing the estimated bad debts expense is quite straightforward. Before the fiscal period closes, you record a debit to the bad debts expense for the estimated amount, and a credit for the same amount to the allowance for doubtful accounts.

This puts the bad debts expense on the income statement in the same period as the revenue. The allowance for doubtful accounts is a contra account to accounts receivable, so the net amount of accounts receivable shown on the balance sheet will be a better estimate of the net realizable value (that is, the amount of cash that we expect the asset to generate) of our accounts receivable, compared to simply showing the gross amount owed.

This is the conservatism of accounting: not overstating the value of assets and income, which would make the financial position and financial performance of the company look better than they are. Accounting regulators assume that without this bias towards conservatism, managers would routinely misrepresent the company’s financial situation to make themselves look good. The regulators are not wrong.

Having done the accounting this way, in the subsequent fiscal year when you have to write off any bad debts, you write them off against the estimate that you set up. Let’s suppose you decide to write of a $21 debt. What happens is that you eliminate the amount from accounts receivable by crediting A/R, just as you did under the direct write-off method. So, you record a credit to accounts receivable for $21. The difference is that you don’t debit bad debts expense. You already did that when you set up the allowance. Now, under the allowance method, you debit the allowance for doubtful accounts, using up some of the allowance you created.

These two accounts, A/R and the allowance for doubtful accounts, are the ones that go into the disclosed value of the accounts receivable on the balance sheet. By taking the same amount out of each of those two accounts, the net of the two accounts doesn't change at all. In this example, accounts receivable and the allowance both go down by $21, so the disclosed amount of accounts receivable doesn't change. And of course, because these are both balance sheet accounts, there's no effect on the income statement at the moment of the write off.

Estimating Bad Debts

There are two ways of estimating the potential bad debts that you need to know about. The first is the ageing of receivables method, which produces better valuations on the balance sheet because the estimate is focused on the allowance itself. The second is the percentage of credit sales method, which produces better matching on the income statement because the estimate is focused on the bad debts expense. Let's look at these in more detail.

Ageing of Receivables Method

The ageing of receivables method focuses on the balance sheet. What you're trying to do is accurately estimate the net realizable value of accounts receivable, and you do this by estimating the allowance for doubtful accounts.

This is done by categorizing your accounts receivable by the age of the account. The theory here is that the longer an account is outstanding, the more likely it is that the customers have run into problems and will be unable to pay you.

For each age category that you set up, you have to come up with some sort of an estimate of the likelihood of any account in that category being uncollectible. This of course is going to vary from company to company, depending on the kind of customers they’ve got and the state of the economy. As time goes by and you gain more and more experience with your particular customers, you’re going to do a better and better job of estimating the percentage that's uncollectible. This is the step that requires the management's expertise. Everything else is mechanical, but this is the place where management has the most influence on the receivables number, and therefore on their own financial results. The decision you make will affect both your asset values and your net income. Everyone knows this, though, so you will eventually have to run this past your auditors, but ultimately, you know more about your customers than they do. This is an irreducible problem in accounting: the information asymmetry between what a manager knows and what external parties can observe.

Once you've categorized all the accounts and estimated the uncollectible portion of each category, you just need to add up those estimates. That’s what the allowance for doubtful accounts should be. Because the allowance is a permanent account, it will likely have a non-zero balance forward from the previous period, so you need to adjust the balance to make it match the total you calculated. Together with the gross amount of receivables, this will give you the net accounts receivable number for your balance sheet.

What happens on the income statement? Well, the amount by which you adjusted the allowance account will be your bad debts expense.

Let's look at that calculation in more detail. In the ageing schedule shown above, we have a simple example of a company with $100,000 in accounts receivable. They’ve looked at the dates of all the invoices that they've sent out and found that most of the receivables are still within the first month. In this case, $52,500 are still within 30 days of the company having sent the invoice, and terms are that the customers have been given 30 days to pay. The experience of the company is that in this age category, only 2% of customers have ever failed to pay. Multiplying those two figures together gives an estimated amount of uncollectible receivables for that category of $1,050.

The next 30 day period contains $24,000 worth of invoices. Again, based on past experience, the company knows that there's a slightly higher likelihood that these accounts might not get paid, a 4% chance. Multiplying $24,000 by 4% gives $960.

The 60 to 90 day category, invoices that are two or three months old, contains a total of $11,000 of invoices. The company’s experience with invoices this old is slightly worse, a 5% likelihood that they won't get paid. Multiplying $11,000 by 5% gives $550 as the estimated uncollectible amount.

Finally, in the greater than 90 day category — invoices that have been outstanding (that is, unpaid) for more than three months — there are $12,5000 of invoices. The company knows from past experience that there's a 10% chance that it’s not going to collect on these. Multiplying $11,000 by 5% gives a $1,250 estimate for that age category.

Adding up these category estimates gives a total estimated uncollectible amount of $3,810. What this means is that out of the $100,000 owed by its customers, the company is estimating — based on its past experience — that the amount it will never collect is around $3,810.

All of these figures in this calculation are fairly objective apart from the percentages. Those will vary from time to time as the company’s experience deepens and as the economy improves or worsens, but they are where managers can exert influence on the final amount.

The percentage used for the “greater than 90 day” category, for instance, could be much, much higher. A company might find that instead of a 10% chance of a customer defaulting, there’s only a 10% chance of collecting! That would make the last figure in the table $10,000 higher, changing total assets by $10,000 and net income by $10,000.

And yet companies are under no obligation to disclose the estimate they made, let alone explain how they calculated it. They only have to disclose the net receivable. You will never know the gross amount or the estimate unless you are part of the management team or part of the audit team.

Using the Ageing Estimate

Once you've estimated your allowance for doubtful accounts, what do you do with it? Well, there's two possible situations that you might face.

Debit Balance in Allowance Account

The first possibility is that last year when you did this, you overestimated. Bad debts were not as much of a problem as you anticipated. After writing off bad debts during the year with the method described above (debit to the allowance for doubtful accounts, credit to accounts receivable), you are left with some of the allowance for doubtful accounts still sitting there. The account would have a debit balance.

In this situation, you can see that we have an accounts receivable face value of $100,000, but we've got $400 sitting in the allowance for doubtful accounts from last year. Based on the estimate calculated above, we want that allowance to be $3,810. So, what do we have to do?

We create a journal entry to credit the allowance for doubtful accounts for only $3,410. That's will bring the balance to the amount that we want, $3,810.

What this means, of course, is that the balancing side of the journal entry, the bad debts expense, is going to also be $3,410. This may or may not be a good estimate of the bad debts expense for the year, but our focus here, in the ageing of receivables method, is on making sure the allowance for doubtful accounts is correct. We’re not concerned with inaccuracies in the bad debts expense.

That’s the general rule with accounting estimates: they affect both the balance sheet and the income statement, and you can’t get both right. You have to pick your priorities. In this case, our priority is on getting the balance sheet right.

The amount of accounts receivable shown on the balance sheet will be $96,190. That's the gross amount of $100,000 minus the allowance that we just set up. The details of the calculation, the $100,000 and the $3,810 figures, are not normally going to be disclosed to the average reader of the financial statements. All we're going to show them is that net realizable value of $96,190.

Credit Balance in Allowance Account

The second situation is if we underestimated last year. The bad debts problem was worse than anticipated. As we debited the allowance for doubtful accounts through the year, using it up by writing off bad debts, the total amount of debits that we posted to the account eventually exceeded the credit balance we had set up, and the account ended up with a debit balance instead of the credit balance it would normally have.

In the example shown, we have a debit balance of $1,000. The normal balance for the allowance for doubtful accounts is a credit, so if we overused it by posting more debits than we predicted, we're going to have a debit balance like the one shown.

If we printed our balance sheet at this moment, the accounts receivable amount would be the $100,000 gross amount (a debit balance) plus the debit balance of $1,000 in the allowance for doubtful accounts. That total of $101,000 is obviously nonsense because our customers only owe us $100,000 and they are not going to pay us more than they owe.

The situation is not an error, it’s just the result of underestimating our bad debts situation last year. If we are very good at estimating, approximately half the time we’ll be out a little in one direction and half the time out a little in the other direction. We can’t expect to make perfect predictions of future events, but we hope that we aren’t out wildly in either direction. Here we ended up with a small debit balance. All we have to do is adjust the allowance before we publish our financial statements.

As before, based on the ageing calculation we did, we want the allowance for doubtful accounts to have a $3,810 credit balance. If it's got a $1,000 debit balance at the moment, our journal entry has to be a credit to the allowance for doubtful accounts for $4,810. That will give the account the $3,810 credit balance that we want.

This means that the bad debts expense, which is the other side of the adjusting entry, is going to be $4,810 for the year. Again, because we have decided to focus on the quality of our balance sheet numbers, we don’t care if $4,180 is a good or bad representation of the bad debts expense on the income statement. It’s good enough for our purposes.

Having made this adjustment, we end up with the same balance sheet numbers as before. The accounts receivable is once again going to be disclosed at $96,190, comprised of a $100,000 gross amount of accounts receivable and the $3,810 allowance for accounts that we were after.

In both situations, then, we end up with a net realizable value of $96,190 for accounts receivable, but in one case, our bad debts expense is a little bit lower, the other case it's a little bit higher than might be ideal. And that's fine, as long as our focus is on the balance sheet. And that is what we're doing with the ageing of receivables method.

Percentage of credit sales method

With the percentage of credit sales method, our focus is on the income statement, not the balance sheet. Our goal is to do a good job of matching expenses to our revenue. Rather than estimating the uncollectible portion of accounts receivable, we’re going to estimate the bad debts expense itself.

How do we do this? Well, at the end of the fiscal period, we look at our credit sales for the year, and drawing on our past experience, we estimate the percentage of these credit sales that are likely to be uncollectible. Not the percentage of accounts receivable, but the percentage of credit sales.

The estimate that we come up with will be our bad debts expense for the year. That’s a debit to the income statement, reducing net income. The other side of the entry we just post to allowance for doubtful accounts. So, just as before, the allowance for doubtful accounts and the bad debts expense are the two accounts involved, but this time our focus is on the other side of the adjusting entry.

So here's the calculation. It's a much simpler calculation than the ageing of accounts receivable calculation, but honestly, the calculation in either case is the least of your problems as an accountant or manager. It’s the amount of work involved to come up with the estimate that is going take all your time, because you have to review all your prior history of collecting from customers and somehow apply that experience to the current information, whether it is accounts receivable or credit sales.

In this case, we had $1,000,000 of credit sales during the year, and based on past experience, we know that we have about failed to collect about 0.5% of our credit sales in previous years, on average. (The percentages in this method tend to be smaller, simply because a company’s total sales for the year is generally a much larger number than the amount it is owed by customers at any point in time.) We anticipate, therefore, the same chance of failing to collect these credit sales, giving us an estimated uncollectible amount for the year of $5,000. (You can see the implicit assumption here, that this year our customers will behave as they did in previous years. If we know that the economy is much better or worse than in previous years, we might want to adjust our estimate accordingly. This is true regardless of which estimation method we use.)

Using the % of Credit Sales Estimate

How do we use this estimate to create our adjusting entry at the end of the fiscal period? Suppose after estimating our bad debts expense last year and then using up the resulting allowance for doubtful accounts during the year, we ended up with $400 worth of allowance left over. If our gross amount of accounts receivable is $100,000, we’ll have a net realizable value of $99,600 at this point, prior to doing any adjustments. (So far, this is the same as Situation 1 described above.)

And now we've estimated our bad debts expense for this year at $5,000. We're going to be debiting the bad debts expense for this amount, because that's what we want to get accurate. It was a temporary account, so it would be empty before we do this adjustment, giving it a debit balance of $5,000.

The balancing side of the adjusting entry will be a credit to the allowance for doubtful accounts of $5,000.

Where does this adjustment leave us? Well, the A/R disclosure on the balance sheet is going to be $94,600. Why? Because we had $400 in the allowance for doubtful accounts already, and we just added $5,000 to it, giving it a debit balance of $5,400.

This puts the net realizable value of accounts receivable at $100,000 less $5,400, or $94,600. As before, the only amount that we'd show on the balance sheet would the $94,600 figure, the net realizable value.

We accept the fact that the allowance for doubtful accounts is not necessarily ideal. What is ideal, as far as we're concerned, is the bad debts expense amount, because our focus was on the quality of the income statement numbers.

If we do a good job of estimating the bad debts expense, in some years we’ll end up with a slightly high allowance for doubtful accounts, and in other years we'll end up with a slightly low allowance for doubtful accounts. Overall, however, it's going to be roughly good enough.

If our estimation procedure is inadvertently biased, though, just because we consistently make incorrect judgement calls in one direction or the other, we may find that that allowance doubtful accounts number will grow (or shrink) over time until the net realizable value shown on the balance sheet is materially misleading. When we realize that this has happened, perhaps after five or six years, we may need to do another adjusting entry to bring it back into line. This won't be needed if our method for estimating the bad debts expense just experiences random differences. We will only need to do this if our estimation errors are not random, that is, if they're biased in one direction or the other, and we will only need to do it when the accumulated error in the allowance for doubtful accounts becomes material.

Summary

Let's summarize what we've learned about accounts receivable.

We started out in this lesson by looking at the general concept of accounts receivable and bad debts. Then we looked very briefly at the direct write off method, which is used by companies that don't generally have a bad debts problem. A more sophisticated method of dealing with bad debts would be a waste of their time and effort.

The other two methods, the ageing of receivables method and the percentage of credit sales method, are used, respectively, to produce a better net realizable value on the balance sheet, and a proper matching of bad debts expense to revenue.

Both of those methods will improve the net realizable value shown on the balance sheet, and both of them will produce better matching of revenue and expense, compared to the direct write-off method. However, in the one case your focus is on the balance sheet, and in the other case your focus is on the income statement.

I hope this gives you a clear picture of the accounting issues arising from the business decision to sell to customers on credit.

Whenever you are ready, head to the next lesson!

Title photo: unfinished buildings in Hyderabad, May 2014. Maybe someone was waiting to get paid.