In this lesson, we're going to take a look at a very basic accounting topic, bookkeeping. But because I like to keep things interesting and I'm trying to teach you to think critically about accounting, we're going to take this from a linguistic perspective.

First, I’m going to give you a brief introduction to postmodern linguistic theory. Yes. I know this is an introductory course, but it's only introductory when it comes to accounting. Everything else is up for grabs, so I'm going to jump into the deep end of social theory with you.

Once we've done that, I'll explain how double entry bookkeeping works:

how it records the financial transactions of a business,

organizes them into meaningful categories, and

presents them in the form of financial statements.

This is important for you to understand because it's how corporations tell convincing stories about their financial results.

LINGUISTIC THEORY

So let's have a look at linguistic theory and how it applies to accounting.

The person I want to start with is Richard Rorty. He was an American philosopher who approached the world with two main insights. One was to see language as our way of creating meaning as human beings. The other was to recognize that this process of creating meaning is grounded in solidarity between ourselves and others.

It's not just about creating meaning for yourself, but about sharing it. So Rorty's theory of language has a very profound, ethical component. Solidarity begins with the understanding that other people matter. To be sure people use language all the time to divide and conquer. You only have to look at the political landscape today with deliberate attempts to manipulate words like "fake news" or "immigrant" to divide groups of people against each other. But we get to choose how we use language. That's why it's called ethics.

Rorty argues that meaning isn't something you just find sitting there inherent in objects or events. Meaning is something we generate. We find things meaningful and that's an active, creative generative process, not just a passive process of discovering what is already there.

For Rorty, the creation of meaning through language is an intersubjective process, which means that we all contribute to developing the shared meaning from our own subjective perspectives. When we knock these perspectives together, the rough edges get worn off and we end up with something we can more or less agree on. Often it's less, but this is a process that continues every day. We are constantly adjusting our understanding of the meaning of things through our encounters with other people.

You might think that this is something that can easily be done on one's own, but Rorty argues that we are incapable of perceiving the world in any natural or pre-linguistic way. Language is very much a part of who we are. When we see an object that is red, for instance, we associate that with all the things that the color red means to us. For me, it might be the color of the Canadian flag. For someone else, it might be the color of a flower in the garden when they were a child or their favorite sports team. For a botanist or biologists, the red color might help them identify and classify the object and distinguish it from similar species that are not red.

Yes, the thing that we're looking at really is red, but that fact alone is not particularly significant. What red signifies is something that we bring to the relationship. And there is no way for us to escape this. We cannot know that something is red without it having some sort of meaning for us, whether that's technical or emotional or historical or whatever.

What this means is that everything we can know about the world is mediated by language. Whether reality is "really out there" is not a very useful question to Rorty. Reality in any practical sense is the world as we know it. And that reality is socially constructed through our language.

The other person I want to draw on is French philosopher Jean Baudrillard. Baudrillard starts with the idea that language is about using signs and signifiers - words and images - to lead people towards a meaning. Language is about trying to convey what you mean.

However Baudrillard recognized that the listener or the reader is not a passive consumer of the message. We constantly create meaning for ourselves at the moment we hear or read a message. That's when meaning is created: at the moment the message is consumed, not at the moment it's produced.

What was interesting to Baudrillard about modern life was the way that this process of creating meaning can disconnect signs and symbols from the things they refer to.

Signs get absorbed into culture and begin to float freely, associating with other signs to form new meanings that can be quite different from the original meaning.

Photo: Getty / Kristian Dowling

Here's an example. This is a picture of Jay-Z, the American rapper and record producer. Look at what he's wearing on his head. It's a New York Yankees baseball cap, and it's not just that he's wearing it, but how he's wearing it. It sits at an angle, off kilter. It might even be a bit too big for him in the sense that if he was running to catch a fly ball, it might fall right off.

But he's not worried about that, is he? Because he's not a baseball player and the hat is no longer a baseball cap. It's not part of a uniform. It's not being worn by a baseball player. It's just an icon of New York. And it says more about Jay-Z's relationship with New York than it does about any baseball team.

The way he's wearing it, it becomes a statement, a recapturing and repurposing of a sports emblem for his own cultural purposes. It doesn't sit straight on his head, it sits off kilter: maybe he's making a statement about how black people are required to sit off kilter in American society. Maybe he just thinks that it looks cool sitting at an angle.

Whatever the message, he is taking what was a baseball cap and turning it into something different. A fashion statement. A cultural statement. A proclamation about who he is as a black man in America. It's got very little to do with baseball and everything to do with Jay-Z.

The point is that language the way we use symbols and words to convey, meaning is a product of historical conflict. Language is inextricably linked to colonialism, to class conflict, to race, to power, and importantly, to resistance. Accounting is no different in this regard than any other language. It's not more objective despite all the arithmetic that adds up so nicely.

It's a tool for creating meaning. Just as much as the English language is a tool used by say, Salman Rushdie to create meaning about India and Pakistan. Accounting is about power and domination. And you need to understand that if you want to understand how accounting is actually used in practice.

Accounting is used by corporations to tell a particular story about themselves. The story is intended to be persuasive, convincing. Think about how a novelist draws attention towards or away from different parts of the story, leading you to a particular perspective on a character or an action. In Lord Jim, for instance, why does Joseph Conrad say that the protagonist is 5’11” instead of six feet tall?

Is he saying that Jim is not quite up to standard. These little details, help shape, meaning in a novel. And the little details in an accounting report, do the same thing.

What's different about accounting is that it's not an everyday language used for everyday conversations. It's a highly structured technical language like engineering. And you need considerable training to be taken seriously as a user of this language.

You can spot someone who's not a member of the finance community by how they use or misuse accounting terminology. The use of accounting is very much conditioned and constrained by its use in professional settings, like the financial markets or banks. It's used as heavily regulated. It is embedded in organizational structures and routines. In many ways, the modern corporation is built from the language of accounting.

All of this matters because it gives accounting so much power as a language. Accounting mystifies and confuses as much as it clarifies and conveys. This is a very useful feature of the language.

So what makes accounting distinctive as a language? Well, the most obvious thing is the calculations. Accounting is a calculative apparatus. The fact that the numbers add up is part of its claim to be truthful. There are two totals on the balance sheet, one for assets and one for liabilities and equity. And these totals always match each other.

William Blake, The Tyger

(image: public domain)

The idea that accounting is balanced is not just a metaphor. It's part of accounting's claim to neutrality and objectivity. Yet this hides the profound inequality in the social roles of accounting. This is part of the reason why my website is called Fearful Asymmetry rather than using Blake's line directly. It's not the symmetry that's fearful about accounting, but the asymmetry.

The intricate grammar of accounting, which we're going to look at closely in a moment. Is all part of the mystification of accounting. Accounting is a barrier to entry into the elite class of society. And the gates are guarded by accountants who insulate and protect people with wealth and power. You might think I'm being hyperbolic. I'm not, this is actually what accountants do.

The other thing about accounting is that it's arranged to highlight the claim of one particular group of stakeholders: the shareholders. Accounting could be different, and I'm hoping to produce a lesson on alternative ways of arranging financial statements. In the meantime though. We're stuck with the traditional format that highlights what shareholders get.

Other languages or like this, too. Academic language privileges an academic audience. Flight controllers speak in highly technical ways that are intended for airline pilots. But accounting is unique because it claims to be able to assign financial values to everything and anything, and because the barriers that it creates in doing this are so vital to the distribution of wealth in our society.

Without wanting to beat this drum for too long, just let me clarify exactly what I mean by how accounting is used to tell stories. I need to be clear here because financial statements have such an unwarranted reputation as an objective picture of the corporation.

Just as everyday language is used to create shared meaning and sometimes to impose meaning as we see in political discourse, accounting is used by every corporation to create and reinforce a narrative about itself. Accounting is intended to persuade.

Think about how research and development was highlighted on Apple's income statement in the first lesson in this series. Apple is very serious about its self-proclaimed image as being innovative. The R&D number highlights for the reader how much money Apple spends to come up with new ideas. It's a bit misleading though, because many of Apple's innovative products come from other companies. Apple didn't invent the mouse or the graphical user interface or the touch screen. It built its products on the ideas of others.

Or think about how employers cry poor when they're negotiating a union contract. Accounting numbers are used by them to explain why the company cannot afford to pay workers more or improve their benefits. It's the same in politics where social programs are described as too costly. The framing of resources as being restricted and constrained is an important use of accounting information and is very much connected to the distribution of power in society.

One of the reasons that accounting is considered objective is that the human side of the calculations is hidden inside the black box of the corporation. Every number in the financial statements, depends to some degree on estimates made by the corporation's managers and on the judgment of the managers and the board of directors.

These are all parties that have an interest in the outcome of the calculation. We're going to be looking into the use of estimates in great detail in this course, but for now, I can assure you that there isn't a number anywhere on the financial statements, that isn't the product of a manager's decision. These decisions are all part of the art of storytelling using accounting.

What I want for you is to begin to think critically about all of this. Look at what gets highlighted in the financial statements. Look at what gets hidden. Look at what gets left out of the story entirely, like the corporation's impact on the planet, for instance. A corporation is an artificial boundary around a set of economic activities. So by design, it will leave out, or externalize, certain costs.

Some corporations create a lot of value, but others offload the cost of their operations onto future generations. And accounting is there to help explain why this is perfectly legitimate.

Accounting has been doing this for centuries. It serves particular interests in society. You need to think about who stands to gain from the story of a corporation being told the way it is in the financial statements. You need to learn to take those accounting numbers and construct new stories with them, reframe them, rearrange them, recalculate them.

It's not hard. And I'll teach you how to do it.

THE SYSTEM OF ACCOUNTING

That was maybe a bit heavy-handed, but I do enjoy a soap box. Let's look at the more practical aspects of accounting now.

There are three main steps in a financial accounting system. Recording is about capturing all the significant economic events that occur in chronological order, translating them into financial terms and writing them down in what's called a journal. If something happens that doesn't have economic value, it doesn't get captured. This is why accounting can tell you all about the value of the paper and pens in the storeroom, but nothing about the affair between two coworkers that takes place there. The affair is way more important, but it's no concern of the accountants, so it doesn't get recorded. There are lots of things that accounting leaves out that matter, and lots of things that get assigned to financial value by accounting, that may be the least important thing about them.

Organizing is about taking all the transactions that were recorded and organizing them into categories. All the cash transactions go together. All the inventory transactions go together. All the payroll transactions go together. This moves the transactions from the journal, which is chronological, to the ledger, where everything is categorized into accounts.

The net of all the transactions, such as the cash that came in minus the cash that went out, or the inventory that was purchased minus the inventory that was sold to customers, is called the account balance. The ledger is a tool for figuring out the value of all the accounting categories that a company decides it needs to keep track of.

Presenting is about taking the accounts and account balances from the ledger and arranging them into a coherent, meaningful report. The decision on what to summarize into a single line on the report and what to state clearly is all part of the art of storytelling. So accounting is storytelling because decisions had to be made about what to record and how to categorize it and how to summarize it.

Different decisions would lead to different stories. It's not that the arithmetic will be wrong. The arithmetic will always be right, but the decisions made about accounting policies for a company affect, not just what gets recorded, but how and when it gets disclosed to the outside world. This is how accounting is used to create a shared meaning for the corporation.

Often accounting is quite successful at this. It doesn't take missing an earnings target by much to cause share values to tumble, so the decisions on when and how to break the news to shareholders and other members of the public can have a significant impact on real wealth.

Here's the same thing in graphical form, for those of you who think more visually. The journal is for recording all the transactions that take place between the company and any external organization or person, such as a customer or a supplier or an employee. And think about that for a second. Although employees work for the company, they're an external party when it comes to the payment of wages.

The journal is also where adjusting and closing entries are recorded at the end of a fiscal period. And we'll learn more about those later.

The ledger is where the journal entries are transferred and organized into accounts. This process is called posting the transactions.

The reports are the final form of the story. Mainly these reports consist of the company's financial statements, which are intended for external audiences. But it's worth noting that reports can be prepared for internal management purposes too.

An example of this is the trial balance, which is kind of a milestone near the end of the fiscal period. More on that later, too.

Recording

Now we're ready to get into the nuts and bolts of accounting. We're going to learn how double entry bookkeeping works. We're going to learn about the normal balance of each account and about where accounting information arises. And finally about the most basic component of bookkeeping, which is the journal entry.

Double-entry bookkeeping is the system used to keep track of a company's financial situation. The books that are referred to here are the two lists that historically were kept by hand. Double-entry bookkeeping was invented in the 15th century. And over the next couple of hundred years, it was refined to suit the purposes of colonial empires.

Every amount of money contributed to a new colonial venture, such as an expedition to capture slaves in Africa and sell them into slavery in America, needed to be kept track of.

You may think my example is harsh, but I keep telling you that accounting is about power and I'm not exaggerating. Accounting was instrumental to the slave trade historically and remains instrumental to modern slavery.

Anyway, the company organizing a shipping expedition also needed to keep track of everything that was done with this money. How much was spent on the ship? How much on food and other supplies? How much on the crew? This was very much about demonstrating stewardship as opposed to calculating profit, but all the money raised by the company by selling slaves, or fur, or textiles, needed to be distributed back to the investors. Back then corporations were limited not just in liability, but in time, because the venture would typically come to a close when the trip was over.

The notion of a limited liability company comes from this time, by the way, because if investors could be held liable for the deaths of crew members, they wouldn't be willing to put up their money. There are legal liability was limited to the amount of money they put in. They could not be tried for manslaughter if the voyage went horribly wrong, and they could not be sued for financial losses beyond the stake they'd put in.

A limited liability company is an invention expressly designed to shield investors from responsibility. And the emphasis of accounting on shareholders stems from this.

At any rate, this crude manual system of keeping the books led to the modern system of accounting we see displayed in a corporate balance sheet today. There's two things to take away from all this. First, accounting has been designed from the ground up to privilege shareholders over other stakeholders.

Second, the system of having two lists that must always add up to the same amount is a very useful way of demonstrating correctness.

Here's what those two historical lists look like in modern form:

On the left, you have a list of everything the company owns. On the right, everything the company owes. What it owns is called its assets. What it owes is subdivided into two categories: liabilities, which is what it owes to creditors, and equity, which is what it owes to shareholders. The total of the left-hand side must equal the total of the right-hand side. Assets equals liabilities plus equity.

Basically, everyone mentioned on the right-hand side has some sort of claim on the company. We use a separate name for one class of claimants, the shareholders, because their claim on the company is slightly different from everyone else's. The other claimants, the creditors, are generally entitled to a specific amount related to some previous transaction or event.

For instance, the company may owe a specific amount of money to the bank related to a loan they took out. Or the company may owe a supplier for some goods or services that it purchased. The company must pay the creditor. Often by a certain date, or face penalties.

What the company owes to shareholders is different. The shareholders claim is conditional on how much money the company earns. And while that may be large or small at the moment, It includes all the future earnings of the company, too. This is what makes shares valuable. They represent not just a claim on past earnings, but on future earnings as well. This claim is not limited by any contract, implicit or otherwise.

The other difference between creditor claims and shareholder claims is that the company doesn't legally have to pay anything to the shareholder. It doesn't have to return the price of its shares if the shareholders want their money back. It doesn't even have to pay dividends, ever. If the company does poorly and can't pay dividends, shareholders can complain all they want, but they're not legally entitled to anything.

And if the company posts large profits, the increase in wealth of the company theoretically belongs to the shareholders, I guess, but the company does not have to pay it out. The company can legally hang onto those profits and reinvest them in the business. If the shareholders want to get money out of their investment, they only have two choices. One, try to convince the board of directors to declare a dividend, or two, sell the shares on the open market.

So the amount owed to shareholders is completely conditional on how well the company does, while the amount owed to creditors, the liabilities, are generally speaking limited to some sort of contractual amount. The company can simply pay that amount to the creditor and its obligation has ended.

“The word “creditor” stems from the Latin word credo, which means to believe.

A creditor is someone who believes you’re going to pay them. ”

This status of the shareholders is having a special claim on the company is a product of the history of capitalism. Accounting has been refined over the years, specifically to focus on the value of the shareholders claim. That's why the equity section is separate from the liabilities. Accounting could be different, but thanks to history, it is designed to serve the interests of capital.

Also, thanks to history. We have a special way of designating how amounts are added to, or subtracted from these two lists. Let's start with the list on the right.

The Latin word for someone you owe money to is the same as the English word, creditor. The abbreviation for that is CR. Amounts listed on the right-hand side are called credits because they're owed to creditors. Interestingly, these words, stem from the Latin word credo, which means to believe. So a creditor is someone who believes you're going to pay them. They trust you.

The opposite of creditor in Latin is debitor, which is related to the English word, debtor. The abbreviation for debitor is DR, the first and last letters of the word. I suppose this means that the abbreviation of creditor is also the first and last letters of that word too, but it doesn't make any difference because it's going to be CR either way.

Now the amounts listed on the left-hand side are called debits in Latin, and we use the same word in accounting. Note that debit (D-E-B-I-T) is not the same as the word debt (D-E-B-T), though obviously they're related etymologically. This can be confusing for students because we use the word debts as a synonym for liabilities. I wish this were not the case, but accounting is full of little idiosyncrasies like this. Just remember that debits and debts are two different things. Also, the B in debts is silent.

Every time, the company acquires a new asset, we add debits to the left-hand side of the balance sheet. Every time we record a new amount owed to a creditor, we add credits to the right-hand side of the balance sheet. Debits on the left, credits on the right.

So, debits make the total of the left-hand side go up, and credits make the total of the right-hand side go up. Simple, right?

Suppose the bank lends you some money. You now have some cash, which is an asset, but you also have an obligation to repay it to the bank someday, which is a liability. So the amount of the cash and the amount of the obligation are equal in value.

To record this event of taking out a bank loan, you would use a debit to represent the cash asset and a credit to represent the liability to the bank.

The event is recorded as a transaction consisting of a debit and a credit. The debit and the credit balance each other out in the transaction, so when you add them to the balance sheet, the assets side and the liabilities side both go up by the same amount and everything stays in balance. Debits on the left credits on the right.

Now, here is the real moment of genius in the language of accounting. Suppose you use some of the new cash to buy a truck. Instead of just using regular arithmetic to subtract the cost of the truck from your cash asset, and then add the same amount to your equipment asset, you use exactly the same method that you used for the loan transaction, debits and credits.

In the loan transaction, the debit for the cash you received and the credit for the loan liability balanced each other out.

To record the purchase of the truck, you're also going to use a transaction with a debit and credit to balance each other out. However, in this case, we're not talking about an asset and a liability like we were before. Here we're talking about two assets, the cash and the truck.

And that's the genius: realizing that credits can be used on the left-hand side to record reductions in the value of assets and debits can be used on the right-hand side to record reductions in the value of liabilities and equity.

Why is this genius? Because it means that you're always adding information to the books you're never subtracting or erasing anything. It means that your books will always contain a sequential record of all the accounting events.

Let's look closer at the transaction to record the purchase of the truck. Equipment and cash are both categories of assets owned by the company. To record the purchase of the truck, you need to move some of the value out of the cash account because you gave that cash to the truck dealer and transfer it into the equipment account because you now own a truck.

Remember how a debit on the left increased the value of the assets? We're going to do that with the equipment account, debiting it for the cost of the truck, making the total assets go up. At the same time, we're going to reduce the value of the cash account by the same amount, not by subtracting anything, but by adding a credit.

The debit increases the equipment asset, the credit decreases the cash asset. The net effect on the total assets is nil. And of course the liabilities and equity are unaffected, so the balance sheet stays in balance.

The beauty of this approach is that it gives you a consistent way of recording every business transaction. The transaction will always consist of debits and credits, sometimes more than one of each, but in every transaction, the value of the debits must equal the value of the credits. This ensures that everything stays in balance all the time.

And it gives you a way of catching errors as soon as you write out the transaction. If the transaction is out of balance, you fix it before you update the balance sheet. The ability to catch mistakes right away is a hugely desirable feature of an accounting system.

Also, if you're keeping your books by hand, as was the case for centuries, pesky little minus signs would be easy to overlook. My grandmother was a bookkeeper who did everything by hand, way back when. And she told me how she worked late into the night one time trying to get her books to balance, only to discover that there was a fly leg, the leg from a dead fly, stuck to the page and it was turning a one into a seven.

Tiny little dashes, the size of fly legs are not something you want to place your faith in when you're a bookkeeper, which is why they don't use minus signs.

Let's look at one more transaction, just to show you that the same system works on the right hand side of the balance sheet. Suppose that after a few years of loan payments, interest rates start to go up and you decide you don't like paying all that money to the bank. Your uncle agrees to invest some money in the company so that it can pay off the balance of the bank loan. Let's say the loan balance is $75,000.

This is what the transaction would look like. The normal balance of accounts on the right-hand side is credit. So you reduce the value of the bank loan by adding a debit to the liability section and you increase the value of share capital. By adding a credit to the equity section. Because the transaction was in balance, the overall balance sheet stays in balance.

So that's the balance sheet. It records the value of the assets and the liabilities and the difference between those. So that's the balance sheet. It records the value of the assets and the value of the liabilities. And the difference between those has to be the value of equity. Assets equals liabilities plus equity. Equity equals assets minus liabilities.

Now the general goal of a business is to generate a profit. You do this by taking the assets you own and using them to produce something of value that you sell to someone else. If you sell it to them for more than it cost you to buy it or make it, you earn a profit. Because you're converting your assets into even more valuable assets, the difference between assets and liabilities will grow. In other words, equity will increase.

Simply stating the new amount of assets, liabilities and equity is not particularly informative though, because a business is judged not just on how much profit it makes, but on how quickly it makes it. If you and I both run businesses that earned a million dollars, but you did it in one year and it took me 10 years to do it, your business is more profitable.

So we need a way in accounting of showing how much money a business makes in a given period of time. That's where the income statement comes in.

The income statement explains how the wealth of the company, the equity, changes due to earning a profit or incurring a loss. The revenue you get from your customers minus the expense of producing the goods or services you sold to them, that's the profit. Well, hopefully it's a profit. It could be a loss.

The income statement then is where all the revenue and expense transactions recorded during the fiscal year are presented to the reader. This is a crucial part of the accounting story, because most readers are very interested in learning how much profit the company made.

The income statement calculates the net income, the profit or the loss, and feeds it into the equity section of the balance sheet. That's why I've got an arrow pointing from the income statement into the equity section.

In the equity section, there's a line called retained earnings. This is the total amount of profit earned by the company since it began, minus any dividends that have been paid out to shareholders over the years. In other words, the dividends were earnings that were paid out to the shareholders and what's left are the earnings that were not paid out. They were retained inside the company.

The retained earnings amount that's reported on the balance sheet is actually a calculation. It's the opening balance of retained earnings from the beginning of the year, plus the net income for the year, minus any dividends declared during the year. If you add those together, you get the retained earnings at the end of the year. We'll see how this works in more detail when we get to the lesson on the accounting cycle.

But for now, just remember that the retained earnings amount shown on the balance sheet is not just a simple account balance. It includes the retained earnings from last year, plus everything that happened on the income statement this year.

The income statement itself is divided into two main parts. The first part shows the revenue earned from the customers. The second part lists, all the expenses that were incurred to earn that revenue.

Some of the expenses are directly related to the revenue, such as the cost of goods sold to the customers. Other expenses are simply related to the time period covered by the income statement, such as rent or interest expenses during the year, or wear and tear on the buildings and equipment the company owns.

Gathering all these expenses together and subtracting them from the revenue during the year. Tells you the profit or loss for the year, the net income.

Now, we've seen how balance sheet accounts are affected by the debits and credits of transactions. The normal balances on the balance sheet help us figure out how debits and credits affect the balance sheet.

We want to use the same system of debit and credit transactions for recording revenue and expenses on the income statement, so that we have a consistent system of keeping the company's books.

How do we know then when to use debits and when to use credits on the income statement?

The answer is fairly straightforward. We know that the net income from the income statement feeds into the equity section of the balance sheet, and we know that credits make equity go up. Since revenue increases net income and makes retained earnings go up, revenue has to be a credit. And since expenses reduced net income and make retained earnings go down, expenses have to be debits.

Let's work through some examples.

Suppose you sell something to a customer. That's a credit to revenue, so revenue goes up. That increases net income. This means that the retained earnings calculation on the balance sheet in the equity section will also go up.

This is not a credit to the retained earnings account. The credit went into the revenue account, which changes the result of the retained earnings calculation on the balance sheet, because that's the opening balance of retained earnings plus net income, minus dividends. All we've done so far is enter the credit for revenue on the income statement, which increased our net income. We haven't made any entry to a balance sheet account yet.

“This year’s retained earnings =

last year’s retained earnings

+ net income

- dividends”

So far, the income statement is doing what it's supposed to do, which is explain the change in equity. If we stopped here though, the balance sheet would be out of balance. We need to complete the transaction. How does the balance sheet stay in balance? Well, Either the customer paid you, so cash goes up, or the customer promised to pay, so accounts receivable goes up. Both of those are assets, so assets go up.

So we've got a credit to revenue, which ripples through net income to the retained earnings calculation in the equity section, and a debit to cash or accounts receivable. Assets and equity have both gone up by the same amount and the balance sheet stays in balance.

Let's look at another transaction. Suppose your employees work for you and you pay them their wages. The work they did is an expense for you, so expenses go up. This reduces net income and therefore reduces the retained earnings calculation on the balance sheet. So equity goes down. How does the balance sheet stay in balance? Well, I hope you paid the employees. Assuming you did, this makes the company's cash go down, keeping the balance sheet in balance.

This is how the income statement works. Every revenue or expense during the year changes the net income, which makes the retained earnings calculation go up or down on the balance sheet without having to debit or credit the retained earnings account directly.

For every revenue or expense, something else on the balance sheet changes by exactly the same amount. It might be an asset going up or down, or it might be a liability going up or down. But whatever it is, it perfectly offsets the change in retained earnings and everything on the balance sheet stays in balance.

The last thing to say about this is that the accounts listed on the balance sheet, including retained earnings are all permanent accounts. The balance in those accounts is the result of every journal entry that's affected them since the company began. The accounts on the income statement, however, are temporary accounts. They're cleared out at the end of each fiscal year with the net difference, the net income, being transferred permanently into the retained earnings account.

That leaves the income statement as a clean slate to write on during the next fiscal year. The income statement will always show only the revenue and expenses that have occurred since the beginning of the year when the slate was cleaned.

That's why the retained earnings calculation on the balance sheet works the way it does. The opening balance of the retained earnings account includes all the net income from last year, but none of the net income from this year. The net income for this year is only recorded in income statement accounts, the revenue and expense accounts.

If you tried to publish the balance sheet with only the balance in the retained earnings account, the balance sheet wouldn't balance because all the credits for revenue and debits for expenses went over onto the income statement accounts. You have to add those to the balance in the retainer needs account if you want the balance sheet to balance.

This will become clear to you as you work through some bookkeeping transactions on your own. I'm going to show you some examples later in this lesson, but I encourage you to do some bookkeeping exercises on your own as well, so that you can develop your own feel for how everything hangs together in the system of accounting.

So far, we've seen how the normal balances on the balance sheet and income statement help us work out how to record individual bookkeeping entries. We've also seen how every transaction involves at least one debit and at least one credit. That's the "double" in double entry. And the debits and credits of each transaction balance each other out.

But how does a company make sure it records all its transactions?

Regular business events, such as sales and expenses need to be captured at the point of sale. Even small stores like coffee shops use a point of sale system now, but it's possible to use paper receipts and then enter the sales total into the accounting system at the end of the day.

All the company's transactions with the bank have to be recorded, too: bank deposits, cheques, and so forth. The company needs to establish routines to enter those into the accounting system and verify the accuracy of the records.

Then there's the payroll. All the wages and benefits have to be recorded, as well as the employees' personal income tax deductions, which have to be remitted to the government by the employer. This is all heavily regulated by employment law, so it's rare to see a company that pays employees manually. If you do see this, you can bet that the employer is dodging responsibility for withholding income tax, and they're probably not paying overtime properly either.

All of these regular transactions can be captured through some combination of manual and computerized accounting processes. For every possible kind of transaction, there's an app that will capture it and feed it into the company's accounting system.

Irregular business events need to be recorded too. If the company purchases an asset like a factory or sells a truck or borrows money from the bank or issues, new shares, those are all important financial events that have to be recorded in the accounting system. They don't necessarily happen every month though. So the procedures for these will be somewhat less routine than the daily events of buying and selling and banking. Regardless of how these transactions are captured, however, they all need to be recorded properly. And this is where the journal comes in.

Here's what the journal looks like. This is a slightly simplified version. Actual journals may have additional columns to track other information, such as invoice numbers or payroll numbers, but the basic columns are shown here.

Starting on the left, you need a sequential reference number of some sort for each journal entry so that you can track its effect throughout the accounting system.

You also need to record the date of the entry.

You will need to know which accounts are affected, such as cash or the bank loan or supplies. I'm using the description column for this. Most accounting systems will use an account number to designate each account. I've just shown the name of the account to make our example more readable.

You'll then want to list the debits and the credits of the transaction. There's always at least one debit and at least one credit, and the total of the debits and the total of the credits will always be equal, for every transaction. Even transaction #3 balances in this example, with a $12,000 debit and a total of $12,000 of credits.

Notice that the debits are listed in one column and credits are listed in another. This spatial arrangement makes it easy to follow what's happening in any transaction. And it makes it easy to see if the transaction balances properly. This is a huge improvement on using adding and subtracting, because minus signs don't give you the same visual sense of things. Arranging transactions in this way, with debits on the left and credits on the right, taps into a different way that our minds work. Visual thinkers especially appreciate this way of laying things out.

Notice also that the purpose of every journal entry is recorded, shown in italics here. "To record sale of shares for cash." "To record purchase of furniture." These descriptions can be written. However, the accountant wants, they might include more information such as how many shares were sold or the type of furniture purchased or the serial number of a piece of equipment that was bought or sold. The description is just a field where any useful information about the transaction can be stored to make it easier for the accountant to recall what was going on.

Just to review then, a journal entry consists of at least one debit and at least one credit, and no matter how many debits and credits are involved, the total of the debits balances with the total of the credits.

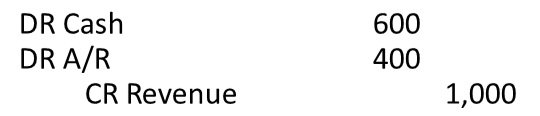

In the example, shown here, a company has sold $1,000 worth of goods or services to a customer and has received partial payment of $600. The rest of the amount, $400, is still receivable from the customer, so it's put into an account called accounts receivable. Accounts receivable is an asset because it's a legal right to the money owed by the customer.

The revenue is the only part of this transaction that affects the income statement. The other two parts affect the asset side of the balance sheet. Also, note that journal entries don't usually have a currency sign beside each amount. This transaction could just as easily have been in euros or shekels or rupees.

The context is usually clear because only people working inside the company see these transactions and they know where the company operates. If there's any ambiguity, the journal would specify that the amounts shown are in a particular currency.

Also notice that there's a very fundamental accounting assumption at play here, which is that any and every transaction can be measured in money. The monetary value of a transaction may be the least important thing about it, but it's only the monetary value, however irrelevant it may be, that gets recorded. If Ryan Reynolds comes into your coffee shop to buy a latte, the price of the latte is the last thing you're going to mention to your friends. But that's all the accounting system is going to remember.

Journal entries come in three varieties. The most common variety is the transaction entry. Transaction entries record the value of each economic exchange with another company or individual. Because this is the main thing that businesses do, there will be many, many more transaction entries in the journal than either of the other two kinds of journal entry.

Transaction entries are recorded at the time the exchange takes place. Selling the coffee to Ryan Reynolds was the transaction, so you'd record the revenue of the sale, the increase in cash, the expense of the coffee, and the decrease in coffee inventory, at the moment you gave Ryan the coffee. We'll get into the details of sales transactions in a later lesson, but suffice to say, you gave Ryan some coffee and he gave you some cash. So, that's an economic transaction and we record that in the journal as a transaction entry.

The second most common variety of journal entry is the adjusting entry. These look very similar to transactions. In fact, all journal entries look very similar because they involve debits and credits that balance each other out. Adjusting entries aren't triggered by economic exchanges, though. They are triggered by the passage of time.

If you prepaid a year's worth of insurance, that would be recorded using a transaction entry because you purchased an intangible asset, the right to 12 months of insurance coverage, by exchanging it for another asset, your cash. So debit to prepaid insurance, credit to cash. The prepaid insurance would then get converted into a series of 12 monthly expenses using adjusting entries. Each adjusting entry would reduce the remaining balance of the prepaid insurance by 1/12th of the original cost of the policy, and put an insurance expense on the income statement for the same amount. The adjusting entry would be a debit to insurance expense, credit to the prepaid insurance asset, reducing it.

Adjusting entries do not involve any other entity. There's no economic exchange happening. They're purely internal adjustments within the company's own accounting system that record the impact of the passage of time on assets and liabilities. In this case, the debit to insurance expense reduces net income, which reduces the retained earnings line on the balance sheet. The balance sheet stays in balance because the credit to prepaid insurance reduces the value of the prepaid insurance asset.

That was an expense example, but you can also have adjusting entries that recognize revenue. For instance, the insurance company, in this example, would deal with the same passage of time by creating its own adjusting entry to recognize the revenue returned by providing you with insurance coverage over the past month.

Their original transaction, when you bought the insurance policy, would have been a debit to cash for the amount you paid them, and a credit to unearned revenue to acknowledge their liability for the insurance the company had promised you, but can only deliver to you as time passes. Each month their adjusting entry would be a debit to unearned revenue to reduce that liability by 1/12th, and a credit to revenue to recognize that they've earned that much of the revenue. That increases their net income and boosts their retained earnings, balanced by the reduction to their unearned revenue liability.

Adjusting entries therefore reflect the passage of time. They're created at the end of the fiscal period, just before publishing the financial statements, to ensure that the balance sheet shows the effect of the passage of time on any assets or liabilities that are affected, and to ensure that the income statement shows any revenue or expense that needs to be recognized because of the same passage of time.

The final variety of journal entry is a special one. It's the closing entry. This is the one that happens after the financial statements have been published. It clears out all the temporary accounts on the income statement, and puts the net difference, the profit or loss for the period, permanently into the retained earnings account in the equity section.

Again, this is done after the financial statements have been published so that the income statement contains all the revenue and expense information for the year. But once those statements have been published, the closing entry can be done to permanently post the net income figure to retained earnings and create a clean slate on the income statement for recording the revenue and expenses of the next fiscal period.

Journal entries, no matter which of the three kinds you're talking about, record the economic activity of the company in sequential order. The debits and credits of the journal entries get posted to the company's ledger, where they're organized into accounts.

Let's have a closer look at those.

Organizing

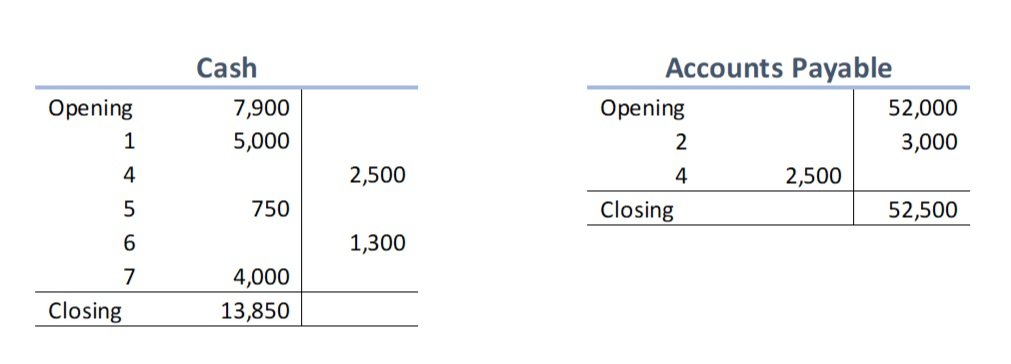

The basic unit of organization in financial accounting is the account. Here we see the cash account and the accounts payable account. You know what a cash account is, it's an asset account, so it contains the debit side of every transaction that increased the company's cash, as well as the credit side of every transaction that decrease the company's cash.

Here the cash account had a balance of $7,900 in it. When the fiscal period began. Remember that balance sheet accounts are permanent, so they will carry forward their balance from the closing of one fiscal period to the opening of the next. We can tell that the cash balance had a debit balance because the $7,900 figure is shown in the left-hand column. Debits on the left credits on the right.

Then we see a series of debits and credits listed for transactions. 1, 4, 5, 6, and 7. Those were the reference numbers used when the transactions were entered into the journal, and we can always go there to find out what the transaction was about and what other accounts were affected.

The total at the bottom, $13,850, is the net of all the debits and credits above it. If you add them up in your head, you'll see that the debits total $17,650, and the credits total $3,800. The difference is $13,850. This is a debit balance because the total of the debit succeeds, the total of the credits.

And because it's a debit balance, the $13,850 figure at the bottom is shown in the left column, where the debits go. If the total of the credits exceeded the total of a debits, you'd have a credit balance and the figure shown at the bottom would be in the right-hand column, where the credits go.

It's quite possible for the credits in the cash account to exceed the debits. Anyone who's ever overdrawn their bank account knows this. But normally companies expect to have a positive amount of cash on hand. So the normal balance of a cash account is a debit.

The other account that's shown is accounts payable. This is money that's owed to suppliers, so it's a liability. That means it normally has a credit balance. Here, the opening balance was a $52,000 credit. Two transactions were recorded involving an increase in accounts payable of $3,000, a credit, and a decrease of $2,500, a debit. We don't know what those were about, but we could easily go look at the journal to find transactions 2 and 4 and read the descriptions.

The net result is a slight increase of the balance in the accounts payable account to $52,500, which is a credit balance, so it's shown in the right-hand column. Debits on the left credits on the right.

These are often referred to as T-accounts, by the way, because of the line across the top and the line down the middle.

I guess the lines across the bottom are optional.

If we list all the accounts in the ledger together in the same report, they'd look something like this:

Every accounting system available will give you a ledger report if you ask for it, and the format will be slightly different from system to system. But the basic information shown here is pretty much standard.

You have the name of the account, you have the opening balance of the account, followed by the debits and credits showing the impact of each journal entry on the account. And somewhere, often in a column towards the right-hand side of the page, you'll see the running balance of the account so you can track the changes in the account balance from line to line. You're probably familiar with this kind of report from looking at your bank statement.

There will usually be a column showing a reference number of one sort or another, allowing you to cross check the information to other reports. And this example, I've only got one reference number, which links to the journal. If this was an actual ledger from a real company, you might see other kinds of reference numbers. For instance, entries listed under the payroll account might include the employee number so that you could cross check the information against employee records.

The ledger, then, will include accounts for every type or class of assets. For instance, there might only be one property plant and equipment account for a small company, while a larger company might have separate accounts for every type of equipment they own. Trucks in one account, computers in another.

This helps the company organize its records into useful groups, and it helps the company apply its accounting policies consistently. The way the company accounts for wear and tear on trucks may be different from the way it accounts for its computers becoming obsolete over time. Both the truck assets and the computer assets gradually become less valuable over time, but the rates at which they do this might be quite different, so the company needs different accounting policies for each of these classes of assets.

The same thing goes for liabilities. All accounts payable will be grouped together. Keeping track of all the company's obligations to its various suppliers, while unearned revenue and long-term debt would be in different liability accounts.

Of course the same thing goes for every account related to shareholders' equity. This includes: share capital, which shows the value of the shares issued to the shareholders; the retained earnings account, which shows all the company's earnings from previous fiscal periods that have not been paid out as dividends to shareholders yet; and the temporary accounts for revenue and expenses that are presented on the income statement.

The net difference between the revenue and expense accounts is also included on the balance sheet where it's added to the balance in the retained earnings account. This allows the balance sheet to show the company's retained earnings through to the end of the current fiscal period.

And that's it. That's all the categories of accounts in the ledger. They all show up on the balance sheet or income statement one way or another. They may also be reported separately on other financial statements or in the notes to the financial statements, to provide a detailed breakdown of certain aspects of the balance sheet or income statement. We've already seen examples of these in the lessonon Apple, and we'll see more in later lessons.

It's worth noting that these are also the accounts used to create the cash flow statement. The cash flow statement has quite a different purpose from the balance sheet and the income statement, so it rearranges the accounts quite drastically. This creates new information out of the same set of accounts. I'll deal with it in a separate lesson.

Just a quick word about sub-ledgers. You'll hear this term if you hang around the accountants in your company. It's not particularly important to anyone outside the accounting department, but you might as well know what it means. The general ledger is the parent ledger. If you will. Every company has a general ledger and for small companies that may well be all they need to do an effective job of bookkeeping.

Large companies, however, need to track thousands of inventory items, thousands of payroll transactions and millions of transactions with customers and suppliers. They use sub-ledgers to organize all this information. There'll be some mechanism for transferring summarized information from the subledgers to the general ledger every month to keep it updated.

But that's all a sub-ledger is.

Presenting

Okay. So we've now reviewed how the journal is used to record accounting information. And how the ledger is used to organize it into accounts. Now we'll look at how the ledger is used to produce reports for people to read.

The trial balance is the simplest report. It's only distributed to people inside the company. I suppose it's also useful to the company's auditor to check the accuracy of the company's accounting system, but basically the trial balance is just for internal purposes. All it does is list the accounts from the ledger together with their debit or credit balances, to show that the ledger as a whole is in balance.

If you do this before you publish the company's financial statements. It will help you ensure that you've done all the right steps, like posting from the subledgers to the general ledger or posting the necessary adjusting entries.

It's not going to be much help to detect that a single sale was entered with the wrong date, but will help you notice if you forgot, for instance, to post all the transactions from the accounts receivable sub-ledger.

Printing a trial balance confirms that the general ledger is in balance, but with automated systems, that's a mere formality. They don't let you get out of balance in the first place.

The accounts are listed in the order in which they will appear on the balance sheet. You have all the permanent accounts first. With asset accounts followed by liability accounts and then the equity accounts. Then you've got the temporary accounts with revenue accounts followed by expense accounts.

Nothing magic about it. It's just a list with totals at the bottom for all the debits and credits in the system.

Now we finally get to the part where a company publishes its financial statements. This has to wait until all the transactions have been recorded and all the adjusting entries have been made. At that point, all the account balances will be accurate and up-to-date to reflect the company's financial situation at the end of the fiscal period.

Unlike the trial balance, the financial statements involve a huge amount of summarizing and rearranging. The trial balance lists every account, but the financial statements grouped them together to make the information more useful to external audiences. Or alternatively, to hide details from external audiences.

For instance, the company might have had hundreds of bank accounts in different countries, in any number of accounts for very liquid financial securities that are almost like cash. These all have to be converted to a common currency and added together to produce a single line on the balance sheet called "Cash and cash equivalents."

Summarizing the accounts is necessary for any big company, because apart from internal accountants and the company's auditors, no reader would find a list of every possible account balance useful. You need to summarize things to make the accounting story understandable. It's just like when you tell your friends about your vacation. You need to leave out a lot of detail if you want to avoid boring them to death.

Every company publishes a balance sheet, an income statement, and a cash flow statement. I've shown you examples in previous lessons. These statements are required for any publicly traded company. If you want to trade your shares on the stock market, you have to meet the disclosure requirements.

Other minor reports link the three main reports together.

For instance, the Statement of Changes in Equity documents how the equity section of the balance sheet has changed during the fiscal period, taking into account not only the net income, but also any changes in share capital from issuing new shares or buying shares back from shareholders. It also lists any dividends that were declared.

The Statement of Comprehensive Income explains any change in the value of assets and liabilities that was not already explained by the income statement. This can happen when a company owns particular kinds of financial investments that go up and down in value on the financial markets. Or when currency fluctuations affect the value of the earnings reported by the company's foreign subsidiaries.

These linking statements are fairly technical, so we're not going to spend a huge amount of time on them in this course.

The final part of the company's financial statements. And in some ways the most important part if you're trying to think critically about accounting, is the notes to the financial statements. We are definitely going to spend time in this course looking at these. The notes are a treasure trove of details, and the first place we want to look when digging into a company's financial results.

This brings us back to the question of how accounting is used by companies to create a story or narrative about themselves. It all starts with what we first observed about the language of accounting. Accounting is not a general purpose language. It's been designed and refined over hundreds of years to privilege shareholders and investors as its target audience.

“Accounting is tone-deaf.”

It's also quite tone-deaf as a language, quite unnuanced, because it only considers the economic value of things.

You know the Jane Austin novels or Bollywood movies where some of the characters see marriage as an economic proposition? If you only think of the world in terms of money, you miss out on all the beauty and romance. Accounting is incredibly instrumental and reductive in its approach to the world. It gets away with this because the picture of the world that it creates is so useful to people with power and wealth, and because the arithmetic makes it appear so correct and objective.

Managers use these characteristics of accounting to shape the narrative around their company. They can highlight some things, like apple does with its research and development, and conceal other things. A mandatory disclosure can be placed deep in the notes where casual readers will never see it.

Discretionary disclosures can be collapsed together in general categories like "Other expenses", which reveal almost nothing. This gives managers considerable power to affect what people think about the company.

This gives managers considerable power to affect what people think about the company. Power doesn't exist without resistance, however. The meaning of a financial statement is not fixed and people can resist the message that managers try to impose.

They can do this because, as Jean Baudrillard argues, meaning is created at the moment a sign is consumed, not at the moment it's created. Remember Jay-Z and the baseball cap.

You get to wear your accounting hat however you like. You get to reframe and repurpose accounting information to create new meanings that are useful to you. We do this all the time with social media content, editing and repackaging videos to create memes. Music producers do this all the time, too, sampling and reusing other people's music to create new compositions.

Accounting is no different. You may need a license to call yourself a professional accountant, but you don't need anyone's permission to re-edit and reuse accounting information to tell new stories.

SUMMARY

Here endeth the lesson. Let's sum up what we learned.

I introduced you to a linguistic perspective on accounting, drawing on postmodern linguistic theory where the meaning of an object or a text is created at the moment of consumption, not the moment of production.

We talked about how accounting, because of its emphasis on calculation and it's arcane system of recording, organizing and presenting information, is presumptively correct.

We talked about how that puts managers in a powerful position to shape the narrative around a corporation.

We also talked about how we as the readers can resist the narrative that managers want us to believe, and how we can reframe and repurpose accounting information to create counter narratives.

Along the way we also learned the mechanics of bookkeeping, so this hasn't just been a fanciful excursion. As we get further into this course, I'll be helping you understand and practice the mechanics of bookkeeping. And I'll also be helping you learn how to reframe and repurpose accounting information.

I hope you're enjoying this learning process. If you have any questions, don't hesitate to reach out to me. My contact details are available in the “About” page of this website. You can also find me at the Schulich School of Business. Thanks for joining this course! Now, on to the next lesson…

Title photo: the Bodleian Library at Oxford University. They are good at keeping books.