Accrual accounting is how organizations keep track of their financial performance. This is not just about how much money they have in the bank, but about how well they are doing at using their assets to accomplish their goals. Accrual accounting includes lots and lots of factors that simple cash accounting leaves out, like past investments and future obligations. Accrual accounting is used by for-profit companies, non-profit organizations, and government entities alike. It lets them see the big picture.

This lesson covers the basics of accrual accounting. And by basic, I mean really basic.

Here's what we're going to cover:

We’ll look at our first make-believe little corporation, Pat’s Courier Company, to help us understand the difference between accrual accounting and cash accounting. You’ll learn why accrual accounting is better than cash accounting for assessing an organization’s financial performance.

We’ll map out the four elementary possibilities for any accrual accounting transaction.

Then we’ll look at how the income statement and the balance sheet are linked to each other, so that we can understand how accrual accounting transactions affect them.

Then we’ll go through a series of simple business transactions to show how they would be recorded using accrual accounting. We’ll be using our second make-believe corporation, Child’s Play Limited, as an example.

Let’s go!

Pat’s Courier Company

Our first example is Pat's Courier Company, a small fictitious company that is just starting up. Let’s see how the first two years of operation compare under cash accounting and under accrual accounting.

Pat purchases a truck for $50,000 and uses it for two years to ship parcels for customers. Following normal business practice, Pat sends out invoices to customers for the work done each month and gets paid later. Let’s assume that Pat bills the company’s customers a total of $6,000 per month, every month, and collects from them the following month.

For fuel and maintenance, I'm imagining that Pat has $1,000 per month in expenses and pays cash for them. I’m also imagining that the company has an employee (it might even be Pat) who is going to be paid a wage of $2,000 per month. To help us see how accruals would be used for employee wages, let’s assume that the employee works all month and is paid on the first business day of the following month. This happens every month for two years.

Cash Accounting

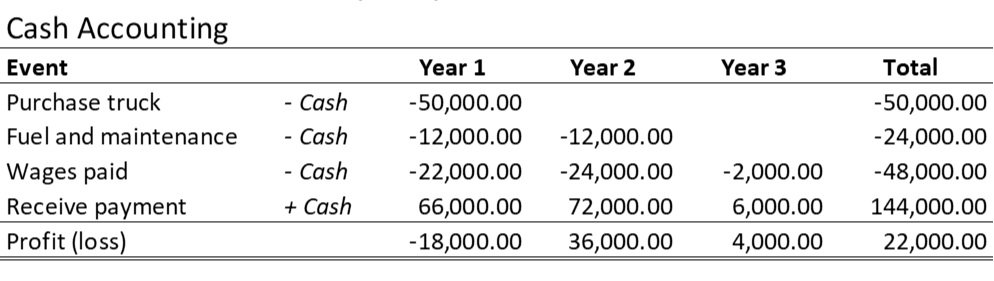

Here's what Pat's Courier Company looks like under cash accounting. All I've done in this table is list the events from the first two years of operation, grouped together by the kind of transaction I described above. I’ve also grouped them into columns based on the year that each exchange of cash occurred.

The first thing that happened, of course, was that Pat purchased a truck. So we see a cash outflow of $50,000 in the first year.

The next thing that had to happen, no doubt, would be Pat filling up the vehicle with fuel. You can’t drive a truck without fuel in the tank. So, we can see that Pat would have a $1,000 expenditure of cash in the first month, $1,000 in the second, $1,000 in the third, and so on, for a total of $12,000 of expenditures in the first year and $12,000 in the second.

For wages, the employee works for the first month and then gets paid the first day of the following month. This continues all year, so in that first year, Pat’s company is going to have 11 payments to the employee for a total of $22,000 ($2,000 x 11 months). The second year there's going to be a payment to the employee in each of the months. And in the third year, we're going to see that final payment to the employee on the first day of the first month in Year 3.

In terms of the money coming in from customers, as we said, Pat bills the customers for the work that is done during the first month and then gets paid the following month. So, in that first month, no cash is received, but in the second month, there's a $6,000 payment, same in the third month, and so on. This is similar to the wages, but it's money coming in, not going out. That makes $66,000 received in the first year ($6,000 x 11 months). Twelve payments come in the second year, and one payment is left over to be received in the third year.

If Pat then simply stops operating the company (to keep our example nice and simple), this would be all the cash going out and coming in during the first three years.

And what does this leave us with? What does the table above, showing cash accounting, tell us?

The interesting thing is that you end up with a very unbalanced view of the profitability of the company. If you look at the total for the first year, it looks like Pat’s Courier Company lost $18,000, but in the second year had a profit of $36,000. In the third year, without Pat even lifting a finger, the company had a profit of $4,000.

This is all very fine for keeping track of overall totals. At the end of operations, when all the cash has been spent and been received, Pat’s company is going to have a $22,000 profit. But this cash accounting approach doesn't tell us how the company did in year one or year two. It looks like they had a terrible year in the first year and a wonderful year in the second, with some gravy left over for year three. This isn’t very helpful because in terms of operating the company: picking up and delivering packages for customers, Pat did exactly the same thing every month for two years. The only things that were different were the purchase of the truck and the one-month delays for paying wages and receiving payment from customers. If the operating activities were identical each year, we need a way of doing the accounting that will show us that they were identical. That way, if the operating activities ever change, we will be able to see the results measured properly in the accounting reports.

Accrual Accounting

Accrual accounting corrects the inaccurate portrayal of economic activity that cash accounting presents. Under accrual accounting, things are done in a slightly different order. Rather than recording the information on the income statement chronologically, as cash goes out or comes in, what you do is record the revenue of the company when it is earned. That is, you record the value of the work you do for the customer when you do it, not when you get paid. (And if it’s goods you are selling, you record the sale when you deliver the goods to the customer, not when you get paid.) This is called “recognizing” the revenue: it simply means recording the revenue in the month in which the work was done, regardless of when the cash is received from customers.

So, in the first month of our example, Pat delivers packages for customers, and that work has a value of $6,000. Pat sends bills totalling $6,000 to the customers and records it all as revenue. Pat gets paid later, but the revenue has been earned because the work has been done.

In the second month, Pad does another $6,000 worth of work for customers, which Pat bills. We’re assuming that Pat also gets paid in the second month for the first $6,000 of work that was done and billed to customers, but that payment is not new revenue. It’s just cash received for the work that was done the previous month.

This continues on each month for two years.

So, in that first year, Pat’s company did $6,000 times 12 months of work for customers, for a total of $72,000 in revenue. This was irrespective of when the payments came in from the customers. The second year, the same thing happens. The company did $72,000 worth of work, $6,000 in every month. No work was done in Year 3.

The next thing that happens under accrual accounting is that Pat (or Pat’s accountant) matches up with each month of revenue, all the expenses that were incurred in order to earn that revenue. This is called “recognizing” the expenses. It simply means recording the expenses in the same month as the revenue they were related to, regardless of when the relevant cash expenditure happened.

Obviously, one of those expenses is the fuel and maintenance every month. That’s $1,000 per month, for a total of $12,000 in each of the two years of operation. Now, that line is going to be the same under both cash and accrual accounting, because the expenditure of cash and the recognition of the expense happen to match up in this example.

Wages, though, are a completely different situation. With wages, the expenditure of the cash and the recognition of the expense are in different months. The wage expense has to be recognized in the month that the employee did the work of delivering packages for the customers, because it was the delivery of the packages that triggered the recognition of the revenue. The payment of cash to the employee doesn’t happen until the next month, but under accrual accounting, Pat’s company recognizes the wage expense when it recognizes the revenue for the delivery.

So, Pat’s company recognizes a $2,000 expense for wages in each month of the first year, for a total of $24,000, and in each month of the second year, for another total of $24,000. That’s $48,000 of expense over two years, the same as cash accounting, but the timing for recording each wage expense is shifted by a month, to match up with the revenue that those wages helped earn.

Accounting for the truck is where the timing differs the most. Pat’s company paid $50,000 in cash for the truck at the beginning of the very first month. Under accrual accounting, rather than recognizing that as one big expense, Pat’s company spreads the cost over the two years in which the company uses the truck to earn revenue. The $50,000 cash expenditure is recognized as an expense in two equal portions of $25,000.

Note that for the wages, cash is paid after recognizing the expense, but for the truck, cash was paid before the expense was recognized.

Here is what everything looks like under accrual accounting:

So what does accrual accounting give us? It gives us a much, much clearer picture of how the company is doing over time. The total column here is identical to the total column under cash accounting, but the individual years are much different. Under accrual accounting, Pat’s company shows an $11,000 profit in the first year and another $11,000 profit in the second year. Accrual accounting is about organizing transactions into the right time periods so that the financial picture comes into focus.

“Accrual accounting is about organizing transactions into the right time periods so that the financial picture comes into focus.”

From an economic perspective, this makes sense because apart from investing in the truck, Pat’s company did exactly business activities in the first and second years: delivering packages, paying employees, buying fuel, and paying for maintenance, and receiving payments from customers. By spreading the cost of the truck over the two years in which it was used, and by adjusting the timing for recognizing monthly revenues and expenses so that they match up, Pat gets a much clearer, much more balanced picture of the profitability of the company.

Cash accounting and accrual accounting both show an overall profit of $22,000 after all the dust settles. However, accrual accounting shows us that the first and second year are equally profitable. Cash accounting showed a big loss in the first year, a big profit in the second year, and a tiny profit in the third year when the company wasn’t actually operating. Accrual accounting permits a clear comparison of different time periods. This means that if accrual accounting ever shows a difference in profitability from one year to the next, people can interpret that as a signal that something has changed. This allows managers to make better decisions, and it allows external parties like lenders or employee unions to understand the company’s financial pictures more clearly.

Four Possibilities in Accrual Accounting

So I'd like to step back then and just think about all the possible configurations for accrual accounting. Accrual accounting deals with the fact that there will frequently be a difference in timing between an exchange of a good or a service from one party to another, and the corresponding exchange of cash in the opposite direction. A company providing a good or service will earn revenue when they deliver the good or service to their customer, but may be paid by the customer either before or after the delivery. Conversely, a company receiving a good (such as a truck) or service (such as work from employees) will recognize the expense for these things as they are matched up to the revenue the earn for the company, and that may be well before or long after cash is paid out for the good or service.

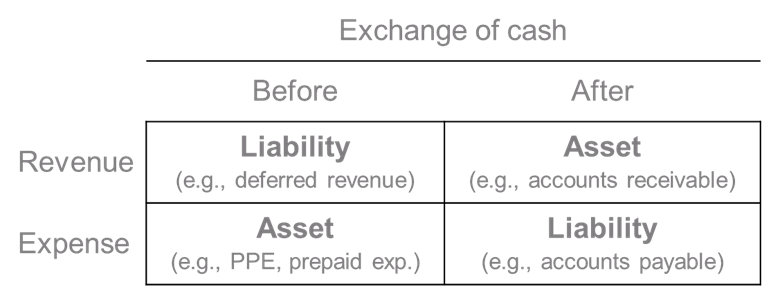

If we map the possibilities onto a simple 2x2 matrix, we get the following:

On the left hand side, you can see we've got rows for revenue and expense. Across the top, we’ve got the different possibilities for when the exchange of cash can happen, either before the revenue or the expense is recognized, or after the revenue or the expense is recognized.

(I'm leaving out the third possibility, which is that the cash could be exchanged at the same time as the revenue or expense is recognized. We saw that situation earlier with the fuel and maintenance expenses for Pat’s Courier Company. When revenues or expenses are recognized in the same period in which the corresponding cash is exchanged, there will be no difference between cash accounting and accrual accounting, so I'm ignoring it here.)

Cash received before revenue recognition

For revenue, then, the first basic accrual situation is shown in the top-left quadrant of the 2x2. It’s when you get cash from a customer before you recognize the revenue, or in other words, before you've actually done the work for the customer.

So for instance, whenever a customer goes into a store and pays for an item they want delivered later, this sets up an obligation on the part of the store. Until the delivery is made, the store has not earned the money it received. The store under an obligation to the customer for the delivery of the goods that were purchased by the customer. In accounting terms, this is a liability.

Similarly, suppose you're an engineering company and you're about to design a building or a bridge for a client. They give you a retainer fee up front. That is money coming in from the client that you haven't actually earned yet. So that creates an obligation towards the client. Again, this is a liability.

In each of these cases, then, the company records the cash received in the asset section of the balance sheet, and simultaneously records, on the other side of the balance sheet, a liability to the customer or client in the same amount. In the examples given, this liability would be called “deferred revenue” or “unearned revenue.” Account terms often have several synonyms.

Up to this point, only the balance sheet is affected. However, when the goods or services are eventually delivered to the customer, the company earns the revenue. At that point, it would record that amount of revenue on the income statement, while crossing the obligation to the customer off the list of liabilities.

Cash received after revenue recognition

The opposite situation is shown in the top-right quadrant of the 2x2. This would be where you have done some work for a customer but they have not yet paid you. This is common in business-to-business relationships, where you sell something to a customer and send them an invoice that they are expected to pay in the future, usually within 30 days. Because you have delivered the goods, you have earned the revenue and you can add it to the income statement. However, because you haven’t received payment yet, you set up an asset on the balance sheet. This asset is intangible: it is a claim on the customer, a legal right to receive payment from them. On the balance sheet, this asset would be labeled as “accounts receivable.”

Cash paid before expense recognition

If you look now at the row for expenses, we have the situation in the lower-left quadrant. Imagine your business pays a lump sump to an insurance company in exchange for two years worth of insurance. At the moment you make the payment, you've paid for the benefit of being covered by insurance. However, the insurance expense will only be recognized as each month passes and you receive the benefit of being covered during that month. Until then, that right to receive insurance coverage for two years, which you have because you’ve paid for that right, is an asset to you. In simple terms, you have paid for something but not yet received it. In this particular case, the asset would be called “prepaid insurance.”

You have a similar situation with property, plant and equipment, strangely enough. It doesn’t sound the same as prepaid insurance, because when you pay for a factory or a truck, you actually receive it. It’s not delivered to you over time like insurance is. However, even though you have possession of the factory or truck, you only recognize the expense over time, as you use it to generate economic value. This expense is called “depreciation,” (or “amortization” – again, there are lots of synonyms in accounting). The point of recognizing the expense gradually is to match the expense of the factory or truck to the time periods in which that asset generated revenue. This is the main principle of accrual accounting: first, recognize revenue when you earn it, and then match to that revenue the related expenses.

We’ll learn more about depreciation and amortization when we talk about long-term assets. The important thing to note here is that cash is exchanged before the expense is recognized, resulting in an asset.

Cash paid after expense recognition

Looking across the expense row of the 2x2, we have the situation where cash is exchanged after an expense is recognized. An obvious example would be where someone does some work for you and invoices you for it. For example, perhaps they came to fix your photocopier or you had them do some routine maintenance on a truck. In such cases, you will recognize the expense when they do the work. Similarly, when an employee works for you today and you intend to pay them on the next pay date, you recognize the wage expense before you pay the employee. In all these cases, you put an expense on the income statement and, instead of your cash balance going down, you put a liability on the balance sheet for the amount you own. The liability would typically be called “accounts payable.”

These are all examples where the expense is recognized right away, as soon as the goods or services are received and before cash is paid. It is worth noting that a liability can still be created when the recognition of the expense becomes disconnected from the receipt of the goods or services, as long as the payment to the other party occurs later. An example of this would be inventory. If you receive goods on credit, you’ll add the liability to your accounts payable. However, the expense is not recognized right away. Instead, you create an asset, “inventory.” Only when you sell the goods to the customer do you recognize the expense (and simultaneously reduce the inventory), because that way the expense matches up with the revenue recognition for the sale to the customer. The liability for the receipt of the goods will be settled when you pay for it, but that may be before or after the goods are sold to your customer. The point is, the recognition of the expense is disconnected from the payment to your supplier because the goods you received are added to your inventory asset. (A very similar situation would occur if you purchased a long-term asset from a supplier and they sold it to you on credit. You end up with an asset that gets depreciated over time, and a liability that gets paid off independent of the depreciation expense.)

So these are the four possibilities for accrual accounting. They have to do with whether you exchange cash before or after the economic event.

Effect of Accrual Accounting on Financial Statements

I now want to go over how the income statement and the balance sheet are affected by accrual accounting transactions. Here is the schematic that I like to use for this. It shows the relationship between the balance sheet and the income statement:

The balance sheet on the left is shown a side by side arrangement. You have assets on the left, liabilities and shareholders' equity on the right. You can see the retained earnings line in the equity section. That line is the one we want to focus on, because retained earnings is where the income statement feeds into the balance sheet.

On the income statement, revenue minus expenses gives you your net income. It’s the net income that gets added each year to the retained earnings. Retained earning starts out each year with the balance that was carried forward from the previous year, and during the year, the income statement accumulates the revenue and expenses to produce the net income number that gets added to the retained earnings.

So that is the linkage between the state of the company at the beginning of the year and the state of the company at the end of the year. The change in the wealth of the company is measured by the income statement, and this is added to the equity section of the balance sheet.

One other thing can happen to the retained earnings line on the balance sheet. That is, if dividends are paid to the shareholders, those come out of retained earnings. Now, that's a transaction that takes place purely within the balance sheet. Cash leaves the company and retained earnings goes down. But that is only possible because the net income from the income statement has been added to the retained earnings in the first place.

Retained earnings is always equal to the retained earnings at the beginning of the year, plus the net income, which is revenue minus expenses, minus any dividends that are issued during the year.

Permanent and Temporary Accounts

Retained earnings always starts with the balance it had at the beginning of the year because it is a permanent account. All the accounts on the balance sheet are permanent accounts. Their balance is the result of all the transactions that have occurred since the very beginning of the company. The transactions just accumulate and accumulate in these accounts. The balance increases and decreases according to the various transactions, but the balance in any given balance sheet account is always the sum total of all the activity that ever took place in it.

In contrast, accounts on the income statement are temporary accounts. They only record the revenue and expenses for the year in question. Then at the end of the year, once all the annual financial statements have been printed, the balances of these temporary accounts are all transferred into the retained earnings account on the balance sheet (which is a permanent account, as we saw). This leaves the temporary accounts with zero balances, providing a clean slate for the next fiscal year.

Basic Possibilities for Accrual Accounting Transactions

There are only so many ways that an individual transaction can affect the balance sheet and the income statement.

Some transactions will affect the balance sheet only. One possibility is that the transaction might occur purely within the asset section. So for example, if you used some cash to buy some inventory, you would have cash going down and you would have inventory going up by the same amount. That will have no effect on the liability section, no effect on shareholders' equity, and no effect on the income statement at all. In fact, it's not even going to have any impact on the total assets. All that's going to happen is you're going to have a lower balance in the cash account, and a higher balance in the inventory account, but the total will be unchanged.

Another possibility is that exactly the same kind of thing could happen in the liabilities section or in the shareholders' equity section. For instance, you could have one liability or equity account going up and another liability or equity account coming down in the same transaction, and everything would still be in balance. The total of liabilities and equity would remain unchanged and nothing else on the balance sheet or income statement would be affected.

An example of this would be when you declare a dividend as a company. When you declare a dividend, retained earnings goes down because the dividend is taken it out of retained earnings. However, on the day the company declares the dividend, the accountants in the company aren’t necessarily ready to send out the cheques to the shareholders. What you end up with, then, is a liability called “dividends payable.” Retained earnings goes down and dividends payable goes up, and everything stays in balance. Meanwhile, the dividends payable liability sits on the balance sheet until the dividend payments are actually sent out.

That brings us to the next possibility. When the dividends are paid out, cash goes down and the liability disappears, meaning that both the assets side of the balance sheet and the liabilities and equity side of the balance sheet go down by the same amount. Everything stays in balance, but the totals at the bottom of each side are slightly smaller. The same things happens when you use cash to pay a supplier who previously sent you an invoice. The payment to the supplier reduces both the cash account and the accounts payable liability. Everything stays in balance.

And quite naturally, you have the other possibility, which is when something happens to make both sides of the balance sheet grow by the same amount. What might be an example of this? Obtaining a bank loan. When you get a loan from the bank, you get more cash in your cash account and a bank loan liability. So both the asset side and the liability side of the balance sheet go up by the same amount, staying in balance.

So that is an overview of all the elementary changes that might happen purely within the balance sheet. Now, as we saw in the schematic diagram above, the income statement feeds into the retained earnings line of the balance sheet. An increase in revenue will increase net income, which increases retained earnings. And if retained earnings goes up, something has to happen elsewhere on the balance sheet to keep it in balance. Either something has to go up on the left hand (asset) side, or something has to go down on the right hand (liabilities and equity) side.

If we've got an increase in revenue, causing net income and retained earnings to rise, one obvious possibility would be that we got paid for it, which mean we had an increase in cash. That would keep the balance sheet in balance. Alternatively, if we recognized revenue for work that we did, but we haven’t got paid for it, we’d have an increase in net income and retained earnings, but instead of cash going up, we would have an increase in accounts receivable. That would also keep the balance sheet in balance.

Now consider an example where both sides of the balance sheet go down instead of up. A simple example of this would be when you've got an increase in expenses, for example, an increase in wage expense by the virtue of all the employees working for a day. That increase in expenses reduces net income and therefore reduces retained earnings. If you pay the employees cash, that reduces the assets side of the balance sheet, matching the drop in retained earnings on the liabilities and equity side, keeping everything in balance. Alternatively, if you don’t pay the employees immediately but agree to pay them on the next pay day, you have an increase in your wages payable liability instead of a decrease in cash: your liabilities go up, your retained earnings go down, and everything stays in balance without affecting the asset side of the balance sheet at all.

Let’s look at how these sorts of changes in the balance sheet and income statement play out when they are linked together in a series of basic business transactions.

Child’s Play Limited

Let’s have a look at how basic accrual accounting transactions affect the balance sheet and the income statement. We’ll put some numbers on them so we can see the cumulative effects of the transactions, and we’ll also think about possible impacts on the other main financial statement, the cash flow statement, so you can begin to recognize the three different types of cash flow.

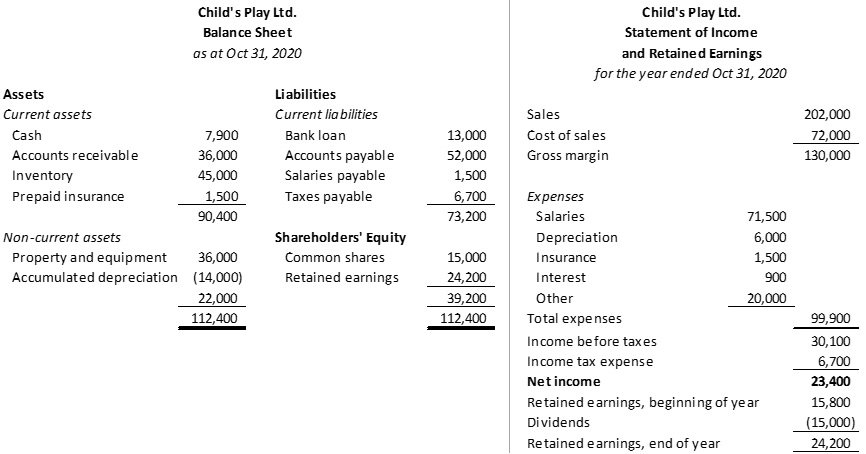

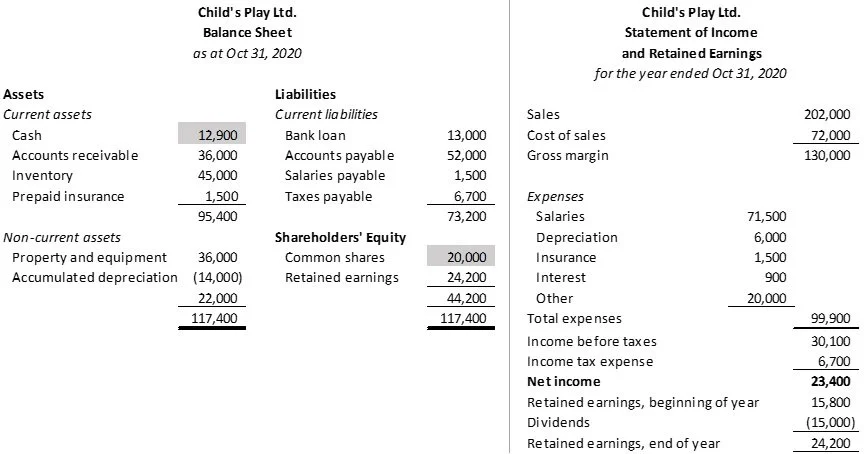

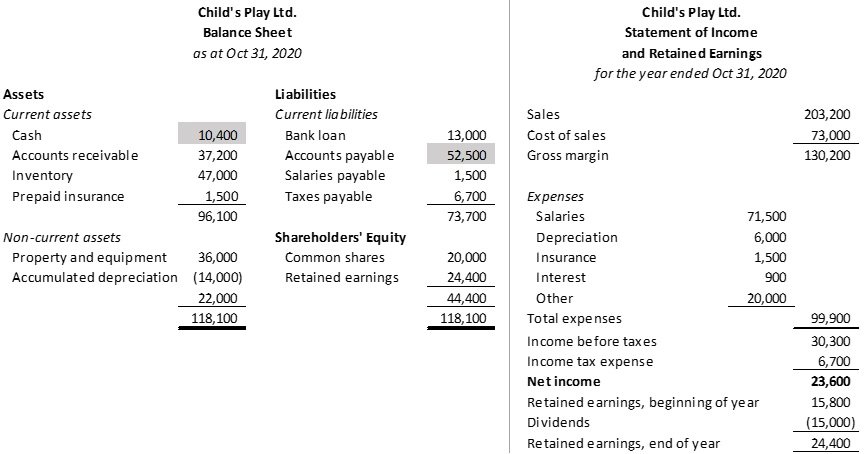

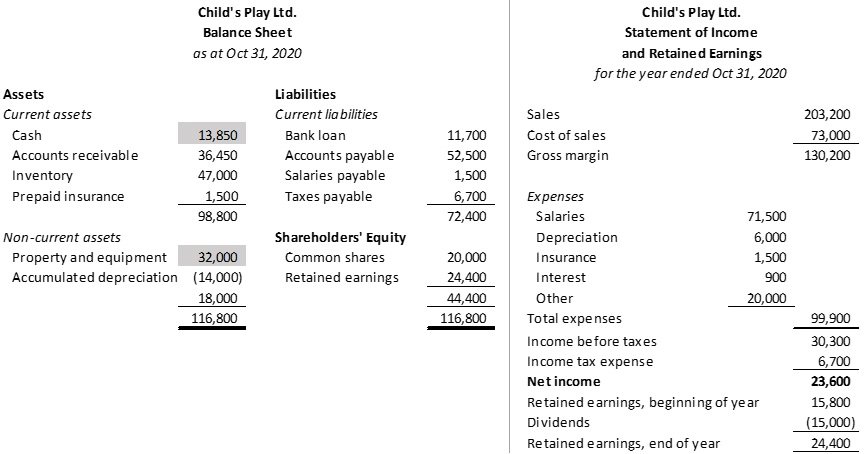

The example that I'm going to be using here is a fictitious company called Child's Play Limited. They've got a preliminary balance sheet as at the end of October, 2020 and a preliminary income statement for the same period. By “preliminary,” I just mean that we have a few more transactions to deal with before we can consider the statements finished.

So, it’s just after October 31st and we're now preparing the financial statements as at October 31st. We have a bunch of transactions that took place during October that we have not yet recorded. So, let's go ahead and enter those transactions and see the effect on the financial statements.

Transaction 1

The first transaction I want to look at is for issuing $5,000 of new shares. Let's say that on October 10th, we issued the new shares and the new shareholders paid for them in cash.

So what happens? We have an increase in cash account of $5,000 and a simultaneous increase in the common shares account of $5,000. Accounts on the left side of the balance sheet normally have a debit balance. Accounts on the right side of the balance sheet normally have a credit balance. So, in this case, the debit to cash makes the left side go up, and the credit to common shares makes the right side go up. So this is the situation that I described earlier, where you have. An increase in assets and an increase on the right hand side. In this case, we have the increase in the cash and the increase in the common shares.

If you recall from the previous statements, the original balance cash was $7,900. So, it's gone up by $5,000. The original balance in common shares was $15,000. It's also gone up by $5,000.

This is a transaction that doesn't affect the income statement at all. When you sell shares, you haven't earned anything and you haven't expended anything. You’ve simply sold some shares to the shareholders, which goes directly into equity, and the cash they paid comes into the cash account.

Now this is a cash transaction, so it is going to affect the cash flow statement. I've not shown the cash flow statement here, but think for a second, what classification would you give to this transaction? The three options on the cash flow statement are operating activities, investing activities, and financing activities. Nothing's happened on the income statement and nothing's happened to any of the working capital accounts, like inventory or accounts payable, so this has nothing to do with operating activities. It’s also got nothing to do with any new assets for the company. There's no new property, plant and equipment, so this is not an investing activity. This has to be a financing activity, which is the category for all the cash flows related to raising money for the company through shares or debt.

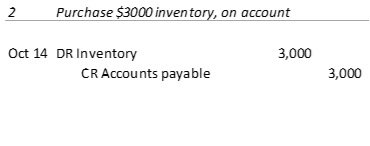

Transaction 2

Our second transaction is a purchase of $3,000 of inventory, and we’re going to assume that the purchase was “on account.” This means that we're going to receive the inventory, but we're not going to pay for it yet. We're going to owe that money to the vendor.

So what have we got here? We have, on October 14th, a debit to inventory inventory on the left hand side of the balance sheet, and we have a credit to accounts payable for the same amount, $3,000.

You can see the effect of the transactions below. Inventory has gone up and accounts payable has gone up. You have an increase on the left hand side of the balance sheet and a corresponding increase on the right hand side. The totals at the bottom of each column change by the same amount, so the balance sheet stays in balance.

So what has happened? We had a transaction that had no effect on the income statement at all, because there was no interaction with a customer, so no impact on revenue, and we haven't incurred an expense. All we've done is we've purchased an asset. When we bring inventory into the company, it is recorded as an asset. It only becomes an expense when we sell the product, at which point it gets recognized as a “ “cost of sales” or “cost of goods sold” expense. But that's not happening yet. All we've done so far is we've received delivery of the inventory, and we owe the vendor for that amount.

What's the overall impact of this transaction on the cash flow statement? We have a change in inventory, which is a working capital account. We have a change in accounts payable, which is also a working capital account. Could it be that we've got an operating activity? No, because there has been no cash flow. No cash has changed hands, so there's no effect on the cash flow statement for this transaction.

Transaction 3

Our third transaction is selling some of that inventory. We're going to sell a thousand dollars worth of it, at a price of $1,200, and we're going to sell that on account.

So there's actually three things happening here. One is we have a transaction between Child’s Play and a customer for a $1,200 sale. And you can see that because the goods have been given to the customer, the revenue can be recognized. Child’s Play has earned it. So, we have a sale in the amount $1,200. However, the customer hasn't paid for the goods yet, so there is a second thing happening here: the customer now owes us $1,200. If the customer had paid cash, we could consider the sales event closed, but because they bought it on credit, there is the ongoing matter of collecting the $1,200. The right to that $1,200 is an asset to Child’s Play, so we put that debit not in cash but in accounts receivable.

You can see the effect of this on the statements below. There is an increase in accounts receivable on the balance sheet and an increase in the sales account on the income statement. Everything stays in balance there because the sale increases the net income number, which also means that retained earnings goes up on the balance sheet. So everything, stays in balance for this part of the transaction.

The remainder of the transaction, the third thing that’s happening, is more straightforward. Child’s Play has to remove the value of that inventory item from its inventory account and recognize the expense on the income statement. It does this at the time the revenue is recognized so that the expense related to the sale appears in the same financial period as the revenue. This is called the “matching” principle for recognizing expenses, and it is as crucial to accrual accounting as the principle of recognizing revenue when it has been earned, not when cash is received.

Inventory, being an asset, is normally a debit account. To make it go down, we have to credit inventory. Now, we don’t credit inventory for the price the customer paid, we only credit inventory for the amount Child’s Play paid to acquire the inventory: in other words, the cost of the goods that were sold. In this example, the cost was $1,000, so we have a thousand dollars worth of inventory leaving the building, reducing that line on the balance sheet. At the same time, Child’s Play recognizes the expense by debiting the cost of sales account. This reduces net income, which means that it also reduces retained earnings on the balance sheet.

Retained earnings normally has a credit balance because it sits in the equity section. Expense accounts, because they decrease retained earnings, will normally have a debit balance. So here we have a reduction of inventory (crediting what is normally a debit account) and an increase in cost of sales (debiting what is normally a debit account, but by extension, reducing net income and therefore reducing the amount being added to retained earnings).

Considering the revenue and the expense together, how does everything stay in balance? Well, let's have a look.

We have an increase in the accounts receivable asset and an increase in sales (i.e., revenue). We also have a decrease in inventory and an increase in the cost of sales. The changes in accounts receivable and inventory affect the left hand (assets) side of the balance sheet. The overall effect of these is to increase total assets by $200 (that is, $1,200 minus $1,000). The sale and the cost of sales both affect the net income number at the bottom of the income statement, which changes the retained earnings on the right hand (liabilities and equity) side of the balance sheet. Net income and retained earnings go up by $1,200 for the sale, and come down by $1,000 for the cost of the inventory given to the customer. This means Child’s Play earned a profit of $200 on the sale, so there is an overall increase of $200 in both net income and retained earnings. Everything thus stays in balance, albeit at new totals.

This can be a little tricky for new accounting students. You really have to pay attention to what happens when transactions affect the income statement. Increases in revenue cause increases in both net income and retained earnings, but increases in expenses reduce both net income and retained earnings.

And what about the cash flow statement? Well, because we are giving inventory to the customer, not cash, and because the customer has not yet paid us for it, there is no cash flow associated with this transaction. There is no effect on the cash flow statement whatsoever.

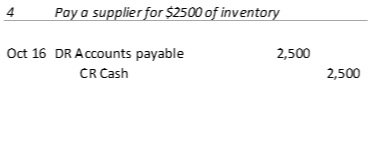

Transaction 4

Our fourth transaction is to pay a supplier for some of the inventory that we bought. We're going to pay $2,500 to the supplier.

So on October 16th, cash leaves the company, so that's a credit to cash for $2,500. This reduces our liability to the supplier, so we reduce our accounts payable by debiting that account by the same amount.

What effect does this have on the financial statements?

We have a reduction in cash, reducing the total on the asset side of the balance sheet. We also have a reduction in accounts payable, reducing the total on the liabilities and equity side. Both of the totals at the bottom of these two columns are going to be slightly smaller, but everything's remains in balance. There's no effect on the statement of income, and therefore no effect on retained earnings.

This transaction does have an effect on the cash flow statement, however, because of the credit to cash. To classify this cash flow, we look at the other side of the transaction, the debit to accounts payable. That's a working capital account, which relates to operating activities. So, this cash flow will appear in the operating activities section of the cash flow statement.

Transaction 5

Let's have a look at our fifth transaction. In this case, we're going to collect some money from a customer. So one of the customers that we had previously sent an invoice to, increasing our accounts receivable, has now decided to pay us. To our delight, they have given us $750 in cash.

The cash received basically cancels out the financial claim we had on the customer. That claim was recorded in our accounting system as an asset, accounts receivable,.

So when we get the increase in cash of $750, we have a corresponding reduction in that other asset, the account's receivable of $750. What does that look like over on the balance sheet?

We have an increase in cash and a decrease in accounts receivable and they offset each other. There’s going to be no change in the balance on the left hand side, no change in the balance on the right hand side, everything's going to stay the same.

And of course, there is no impact on the statement of income or the retained earnings.

What does this mean in terms of the cash flow? Well, we've collected from a customer. That's part of the way that we do business as a company, it's part of our operating activities. So that is an operating cash flow.

Transaction 6

In transaction number six, we're making a $1,300 loan payment to the bank. And if you recall from above, we had a bank loan balance of $13,000. The bank loan is a liability, so it normally has a credit balance. To reduce the bank loan balance, therefore, we’re going to debit that by $1,300.

And where is that money coming from? We're taking it out of our cash account. The cash account normally has a debit balance. So we're going to credit that with $1,300 and we're going to see then a decrease in cash, because of course we've taken cash out and given it to the bank. That’s how we reduced our obligation to the bank for the loan by $1,300.

So everything stays in balance. We're going to have new totals on the balance sheet that are slightly lower than when we started this transaction, but everything will stay in balance.

One of the things that you need to think of when you're looking at the liability section is which liabilities are related to the operations of the company, like accounts payable, salaries, payable, and so forth. Even taxes payable is part of the operations. The bank loan, however, is related to the financing activities of the company. We have here a transaction here that involved cash, so we're certainly going to have an effect on the cash flow statement. Because it's related to the bank loan, that cash flow is going to be classified as a financing activity.

Transaction 7

Transaction number seven is just a little oddball transaction. We're going to get rid of one of our delivery vehicles. So presumably in Child's Play Limited, we have a whole bunch of property, plant and equipment. Some of that consists of vehicles for getting around and delivering equipment and so forth.

So let's decide to sell one of these vehicles. We're just going to put it up on Kijiji, and let's assume that we got paid cash because somebody came over one evening to have a look at our vehicle and gave us $4,000 cash, and they took the keys to the vehicle and drove it away. So what have we got here? We have an increase in cash of $4,000 because this person has given us the money, and we have a decrease in our property, plant and equipment for the value of the vehicle.

And you can see the impact on the cash, and on the property, plant and equipment. So this is a transaction that has no effect on anything except the asset side of the balance sheet. We have a increase in cash and a decrease in property, plant and equipment. There's no change in the balance there.

And of course there's no change anywhere else. Nothing else changes anywhere on the income statement or the rest of the balance sheet.

There is however, a cash flow, right? We have a debit to cash. So what kind of cash flow is it? This is not an operating cash flow because the asset that we sold was not our inventory; it had nothing to do with our regular operations. We sold one of our long-term assets, so this is an investing cash flow. An investing cash flow can be a positive or negative cash flow. If we purchase a new asset, we have a negative cash flow related to investing in one of our assets. If we sell one of those assets, it produces cash for us, so we have a positive cash flow in the investing activities section of the cash flow statement. That's the situation here.

Transaction 8

The final transaction I want to look at here is one that takes place at the very end of the month. Remember we made a payment on the bank loan of $1,300 and it dropped in balance from $13,000 to $11,700. But you know, time passes, so we have to recognize the fact that we have accumulated interest on the bank loan. So, one of the things we need to do as a company, at the end of the fiscal period, is accrue any interest on our loans that has to do with the passage of time. Even though there's no transaction with the bank in terms of an exchange of cash, we've incurred an increased obligation to the bank because time has passed and interest has built up on the loan.

What we do here, therefore, is debit the interest expense account. We're recognizing an expense here, due to the passage of time and the fact that we have incurred this additional obligation. We've received economic value from the loan during this period of time that has passed, so we recognize the interest expense related to this before we move on to the next accounting period.

Here, we're just adding that to the bank loan. Now admittedly, the details for accumulating interest on a bank loan get a little bit more complicated than that. There are a few more accounts involved related to accumulating the interest, but for simplicity's sake, I'm just showing it as an increase in the bank loan itself.

And that's fair because all of those detailed accounts, the ones that we would use to keep track of the accumulating interest, would be added together on the balance sheet anyway, to be shown on a single line. It's worth remembering that financial statements consist of a bunch of lines with numbers associated with them, and each line can represent the net value of many related accounts in the background. For example, the cash line that now shows $13,850, that might be five or six different bank accounts used for different purposes, chequing accounts and savings accounts, that are all added together to come up with that total. Similarly, the bank loan that's shown here on the balance sheet is actually a number of different accounts in our accounting system that are all added together to produce this total.

So what have we got here? We have an increase in the interest expense, which results in a decrease in the net income. So what's that going to do? We're going to have a decrease then in the retained earnings as a result.

So how does the balance sheet stay in balance? Well, remember we added the $300 interest to the bank loan, up in the liabilities section. So we have an increase in the bank loan and a decrease in retained earnings. These cancel each other out, so we have no effect on the total at the bottom. And of course there's no effect on left hand side of the balance sheet whatsoever, so everything stays in balance.

This is an accrual transaction, posted at the end of the month. It increases the bank loan balance, and it decreases retained earnings because of the impact of the interest expense on the income statement. However, this is purely an accrual transaction. No cash is exchanged, so there is no effect on the cash flow statement at all.

Summary

Let's try and sum up what we've covered here. We've had a good look at accrual accounting, using a fairly simple example of a courier company. One of the things I want you to take away from this is the little 2x2 matrix that showed the four different accrual possibilities, depending on whether cash exchanges hands before or after the recognition of revenue or expense.

Then we took an extended look at the link between the balance sheet and the income statement, going through a bunch of different transactions showing the precise effect on the balance sheet and the precise effect on the income statement. In some cases, it affected only one side of the balance sheet, with something going up and something going down. In other cases, it affected both sides of the balance sheet with something going up on one side and something going up on the other, or down on one side and down on the other. In yet other cases, it affected the income statement. So, there might have been an increase in revenue or an increase in an expense that changed net income, impacting the retained earnings number on the balance sheet. And yet everything stayed in balance, as we saw, because something else on the balance sheet went up or down at the same time.

And then the last thing that we covered here was that, for each transaction that had an impact on cash, we classified that cash flow as an operating cash flow, an investing cash flow, or a financing cash flow.

I hope that you have enjoyed this little discussion. Hopefully it makes the basic notion of accrual accounting a little clearer for you.

When you are ready, on to the next lesson!

Title photo: some manual bookkeeping journals from a microfinance project in Sri Lanka (credit: Danture Wickramasinghe, my co-author, for our study of microfinance)