The equity section of the balance sheet has all kinds of curious line items in it. Even the two most basic ones, Share capital and Retained earnings, can be nuanced, and there are other more “exotic” lines in this section that I want you to understand, at least at a basic level. If someone were to put a set of financial statements in front of you and point to one of these line items, I want you to be able with some degree of confidence to explain what it means, how it arises, how it relates to the rest of the balance sheet and how it affects the other financial statements. So, let's go!

Dividends

Let's start by looking at the very important concept of dividends. Dividends are payments a company makes to its shareholders to distribute a share of the company’s profits. Dividends can be paid to preferred shareholders and to common shareholders. Unless we specifically state otherwise, what we're talking about when we say dividends is cash dividends. Stock dividends, the other kind of dividend, are much less common. I’ll describe those in a moment.

Charles Ponzi writing a cheque (credit: Boston Library / NYT, Wikipedia, public domain)

Cash Dividends

So paying dividends means the company is distributing cash to its shareholders, and in order to do that legally, it has to have enough retained earnings and enough cash to pay the dividend. If it falls short on either of those requirements, it's not allowed to pay a cash dividend because that's what we call a Ponzi scheme. Ponzi schemes are when a company sells shares to new investors, and takes their money and pays it out as dividends to existing shareholders, creating the false impression that the company is very profitable and therefore attracting even more investors. Eventually the scheme collapses and someone goes to jail.

It's important to realize that dividends are not an expense on the income statement. That's the one thing they are not. They're deducted directly from retained earnings after the income is calculated. And unlike interest, this means that dividends are not tax deductible. Interest expense appears on the income statement above the calculation of the company’s taxable income. This means that they reduce the income tax that the company has to pay. Dividends, in contrast, don’t appear on the income statement at all, so they don’t affect the tax calculation. A company pays dividends out of its after-tax earnings.

So what kind of companies do pay dividends, then? Well, generally companies that don't have huge growth opportunities in front of them. When a company starts out, its investors don't want it to pay dividends. They want the company to be using its money — including the share capital put in by the investors and any retained earnings it has generated, to invest in new assets and continue to grow and take on new opportunities to earn profits. Think of starting up a gold mining company: if you buy the company’s shares, you don’t want the company to just hand you your money back, you want it to go dig up some gold.

However, as a company matures and runs out of new opportunities, the money that it's generating from its operations should be paid out to the shareholders, once all the company’s expenses have been paid. You don’t want the gold mining company to hang onto its profits indefinitely, and you don’t want its managers to say, “Hey, let’s use these profits to start up a record company!” You invested in gold mining and you have every right to expect the company to stick to that business model.

Stock Dividends

The other kind of dividend, as I mentioned, is the stock dividend. A stock dividend is like a cash dividend in so far as the corporation is distributing its excess wealth to its shareholders. With stock dividends, though, the company issues new shares to the shareholders instead of paying them cash.

What does this accomplish? After all, simply dividing the value of the company by a bigger number of shares just makes all the existing shares worth less than they were before the stock dividend. If you owned 10% of the company with 1,000 shares, a stock dividend might leave you owning 1,100 shares, but you’d still only own 10% of the company, because every other shareholder would have received new shares, too, in proportion to the number of shares that they owned.

Let’s look a the bookkeeping entry for a stock dividend. It’s a debit to retained earnings and a credit to share capital. This records the fact that the company has legally issued some new shares to the shareholders, but what does this accomplish? Nothing changes anywhere on the balance sheet or income statement, apart from the equity section, and even then, the total equity remains unchanged. The only thing that happens is that some value is transferred from the retained earnings account to the share capital account.

And that’s the important thing: because cash dividends are limited not just by the amount of cash available but by the retained earnings, reducing retained earnings with a stock dividend limits the ability of the company to pay cash dividends in the future. The company is basically declaring publicly that it is never going to pay out this portion of its retained earnings as cash, the portion transferred to share capital. If it had $1 million in cash and $1 million in retained earnings, and declares a $400,000 stock dividend, it still has $1 million in cash but now it can only pay out cash dividends of $600,000.

This means that, of its $1 million in cash, $400,000 is now retained exclusively for other purposes than paying dividends. The company could use it to pay employees, suppliers, and creditors, or invest it in new assets — anything but cash dividends.

A stock dividend is therefore great news for all the other stakeholders of the company, because it means that the cash shown on the balance sheet will not be siphoned off by the shareholders.

If you're a lender, you're particularly excited by this because it means you can more safely rely on the company to pay off its debts. Stock dividends don’t change the company’s debt to equity ratio, but they change the interpretation of that ratio because they change the meaning of the equity in the denominator.

The other thing to keep in mind is that stock dividends don't prevent individual shareholders from getting their hands on cash. They're perfectly free to sell their shares to other shareholders and get cash that way. In fact, because a stock dividend divides the market capitalization of the company by a bigger number of shares, it may make it easier for a shareholder to liquidate part of their holdings — just like stock splits do, as we’ll see below.

Shares

The next concept I want to go over is corporate shares. To do this, I first want you to think about what it is, exactly, that you are entitled to as a shareholder that no other claimant gets to have. It’s the concept of residual rights, and it underlies the whole idea of share ownership.

Residual Rights

Residual rights have to do with what happens at the winding up of a company, when it goes out of business — the technical term is “liquidation.” Residual rights are not especially relevant to companies that are going concerns.

Claimants on the company, which we discussed at length in a previous lesson, can be classified according to the priority of their claim. These priorities are established in law, and accounting serves to quantify and disclose these priorities. For example, that is the purpose of separating shareholder claims into a separate section of the balance sheet, the equity section, because that represents what’s called the residual claim on the company’s resources. Residual in this context just means that shareholders get what’s left over after everyone else has been paid what they are owed.

Claimants and their claims can be divided into five levels of priority:

Super-priority claimants

Secured creditors

Unsecured creditors

Preferred shareholders

Common shareholders

I like to start explaining this list with the second line, the secured creditors, because everyone gets this concept. It’s the status that your bank has when you get a mortgage to buy a house. The bank has a lien on your house. This means that if you fail to pay your mortgage, the bank has the legal right to force the sale of your house in order to collect its debt. It cannot force you to sell your clothing or the food in your fridge, but it can force the sale of the house because of its legal status as a secured creditor. In corporate debt, there are lots of instances where creditors have their loans secured. For instance, they might have a lien on the inventory of the company, or on some important piece of equipment that they helped finance.

Above and below the secured creditors, in terms of priority, are two other classes of creditors. Unsecured creditors are the ones who have to wait in line to get paid when the company runs into money troubles, behind the secured creditors. Unsecured creditors will only be paid if there is money left over after the secured creditors have been satisfied.

The legal system in most countries, however, has established a class of claimants that are even higher priority than the secured creditors. These are sometimes referred to as super-priority claimants. For example, employees are often protected from the company winding up and forfeiting on their wages. You’ll find this laid out in the employment standards legislation in, say, the province of Ontario or the state of Maine.

Same thing with pension obligations, and with amounts withheld from payroll for income tax or social security contributions, and for corporate income tax or property tax. Those are the kind of claims that have to be settled in many jurisdictions even before money can be paid out to secured creditors.

That's all the creditors, then: the super-priority, secured, and unsecured creditors. Next in line are the shareholders, and the first priority for settling shareholder claims goes to the preferred shareholders, if indeed the company has issued preferred shares. Any dividends owed or any share capital due back to the preferred shareholders has to be paid first, and only then can the common shareholders step up to the trough. The share capital owed to preferred shareholders upon liquidation would have been specified at the time the shares are issued, typically as some sort of multiple of the issue price of the shares; this allows investors to decide what they are willing to pay for the preferred shares. So, there is a fixed limit to the amount a company will have to pay out to preferred shareholders upon liquidation.

After all the creditors and preferred shareholders have been paid what they are owed, followed the common shareholders get whatever's left. They get the residue, in other words, hence the phrase “residual rights.”

If the company has performed well financially over the years and has lots of assets left, there may be a huge windfall for the common shareholders when the company winds up. This is not usually the case for regular businesses, because they tend not to go out of business when things are going well, but for a company with a fixed mandate, such as a company set up to mine a specific body of ore, the company may complete its operations successfully and then close down. In that case, there may be plenty of value left in the company after the first four classes of claimants have been paid.

Of course, if the company has performed poorly and is being liquidated because it cannot pay its debts, the creditors and preferred shareholders may well walk away with everything the company owns. There may be little or nothing left for the common shareholders. This is the risk of investing in stock. You get the upside of an unlimited claim on companies that do well, but you can lose your entire investment in companies that do poorly.

Preferred Shares

Preferred shares are often issued by established corporations like General Electric that have steady cash flows and can pay out dividends reliably. Preferred shares are therefore often found in the portfolios of older investors who live off their investment income.

Preferred shares, like bonds, are what's called a hybrid security because can they have all kinds of little features built into them to sweeten the pot for investors. These features can sometimes make them seem somewhat like debt instruments, which is why we discussed them in the lesson on long-term debt, where we compared them to bonds. Let me refresh your memory on some of the more important features. Preferred shares:

Usually have no voting rights

May or may not have a fixed term

Are not guaranteed to provide dividends, since unlike interest payments, dividend payments always depend on the company being profitable

May be convertible into common shares, at the discretion of either the investor or the company

May be redeemable at the discretion of the company (put option), or retractable at the discretion of the shareholder (call option) — both of which mean that the shares can be cancelled in exchange for a stipulated amount of money

May be cumulative, which means that the company has to pay any preferred dividends that it skipped before it can pay dividends on common shares

You have to look carefully at the features of any security to see exactly what they offer the investor. Preferred shares are not all created equal, and the features of a particular preferred share will definitely affect its value.

Share of a pie (credit: Sheri Silver, Unsplash)

Common Shares

Common shares are the most common kind of share. That’s a true fact.

Common shares are the ones you’re thinking of when you talk about shareholders voting at the annual general meeting. They can vote on things like the election of directors, the appointment of the auditor, and any extraordinary resolutions that come along.

In any corporation, there might be more than one class of common share: Class A, Class B, Class C shares, and so on. Small family-owned corporations may have different classes of shares for each member of the family, for instance, in order to give the family flexibility in how to distribute wealth to the children. Large corporations can also have different classes, and in these cases, each class of share might have different voting rights. Manchester United shareholders all get to vote at the annual general meeting, but the Glazer family’s shares each come with 10 votes instead of 1, giving the Glazers complete control of the corporation. If you look at Magna International in the past or Bombardier today, you'll notice that shares of the founders of the company gave them many more votes per share than other common shares.

Often, as was the case with Magna and Manchester United, dividends were distributed evenly across all classes of shares, but the control of the key decisions, such as the appointment of directors, was completely in the hands of those who owned the shares with multiple votes per share. Accounting does not show these shares as having a different value because the family shares are not traded publicly. Accounting is very good at ignoring questions of power when it suits the powerful.

One thing to note about common shares is the notion of “par value.” This comes from the tradition of printing a nominal value on each physical share. Today, not all common shares have a par value. A par value has no effect on the market price of the shares.

The bookkeeping entry for issuing shares without par value is simple. Suppose the company issues 100 shares at a price of $100 per share. The entry would be: DR Cash $10,000, CR Share capital $10,000.

If the shares have a par value, the entry is slightly different. If those same shares had a par value of $1, but sold for the same price of $100 per share, the entry would be: DR Cash $10,000, CR Share capital $9.900, CR Contributed surplus $100. The amount of cash the company gets is the same, and the value of the shares is unchanged, but the value of the shares on the balance sheet is shown on two separate lines in the equity section, share capital and contributed surplus.

Stock Splits and Consolidations

This brings us to the topic of stock splits and stock consolidations. Neither of these has any effect on the financial statements of the company, nor its market capitalization. All that happens is that the number of shares goes up or down.

Suppose a corporation has 1,000,000 common shares outstanding and they are trading at $10 each. The market capitalization is therefore $10,000,000. If the company’s board of directors decides to do a 2-for-1 stock split, every existing share is replaced by two shares. If you owned $1,000 of shares, you still own $1,000 of shares. It’s just that before the split, you had 100 shares worth $10 each, and now you have 200 shares worth $5 each.

The purpose of a stock split is to increase the liquidity of the market for shares. If Apple shares are trading at $700 per share, it’s difficult for small investors to buy in. Apple might split its shares 7-for-1, as it did in 2014, making it possible for a small investor to buy a few shares. This makes it easier for all shareholders to adjust their ownership position to suit their portfolio needs.

Stock consolidations work in the opposite direction. (And note, this use of the word “consolidation” is completely different from the idea of consolidated financial statements. That just means that all the financial statements of all a company’s subsidiaries are rolled in with the parent company’s own financial statements, to produce a single set of financial statements for all the corporations controlled by the parent company.)

Stock consolidations combine shares together so that the shareholders each end up with a fewer number of shares, without changing their ownership position. If there were 1,000,000 shares worth 15 cents each, a 10-for-1 stock consolidation decision by the board of directors would leave the corporation with 100,000 outstanding shares, each worth $1.50.

The purpose of a stock consolidation is to prevent the shares from being delisted by the stock exchange where they trade. Stock exchanges require shares to maintain a minimum value. Stock splits and consolidations are decisions by the board of directors, and are accomplished by filing a notice of the decision with the stock exchange, and of course, the decision has to be in compliance with any rules that govern the exchange.

Share Repurchases

A share repurchases is when a company buys back shares from its shareholders. With publicly traded companies, there will be lots of rules governing the procedure, but basically, it’s just the opposite of issuing shares. The company will decide how many shares to repurchase and at what price. It needs to let people know when this is going to happen that all investors have a fair chance of selling their shares to the company if they so choose. Each investor will make their own decision, so it’s quite possible that the company may not be successful in buying back its shares if it offers a price that is too low. That would be embarrassing, so a lot of work is put into coming up with the right offer price.

Reasons for Repurchasing Shares

There are a variety of reasons to repurchase share. It might be done as a symbolic gesture. Suppose the directors know something positive about the company can't disclose it yet. It can do a share buy-back at a strong offer price, to signal to the market what it considers its shares to be worth. The number of shares that it buys back needs to be enough that the market considers it a costly signal to send; if the company only buys back a tiny number of shares, the signal is not credible.

Another reason is to reduce the number of shares on the market. This has the effect of consolidating the control of shareholders who already have a dominant ownership position. Often this will be the CEO or the the Chair of the Board, senior officials who are looking to gain even more influence over the company. This is simply about power.

Another common reason is that the company may be rich with cash and wants to distribute its retained earnings to the shareholders in a way that gives shareholders a choice. If the company pays dividends, all the shareholders get the money, but if it does a share repurchase instead, shareholders who want to cash in can do so, and shareholders who want to stay invested can simply choose not to sell their shares. Those who hang onto their shares will end up with a higher percentage ownership of the outstanding shares, because the shares that other shareholders sold back to the company are now off the market. Each remaining outstanding share will be worth a little bit more, similar to the result of a stock consolidation: the company’s market capitalization is now divided by a smaller number of shares.

A share repurchase can allow a company to distribute its excess cash to shareholders when it does not have sufficient retained earnings to declare a cash dividend. With a share repurchase, a company can even go into a negative retained earnings position. It can’t do that with a cash dividend.

Accounting for Share Repurchases

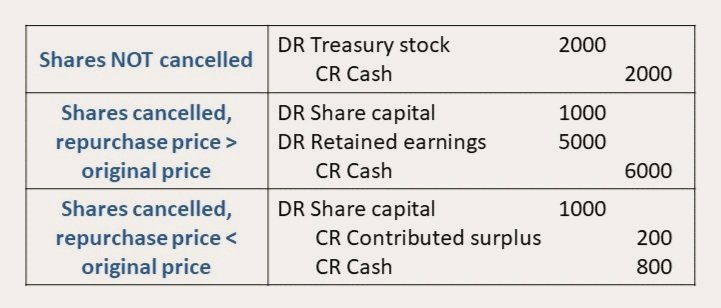

So how does the accounting work? If a company buys back its shares, this reduces its cash and its equity. However, there are three different scenarios that require slightly different bookkeeping entries:

When a company repurchases its shares, it has to decide whether to cancel the shares or keep them in “treasury.” Keeping them in treasury means that they are still considered issued, but they are not outstanding — no shareholder owns them. Only shares that are issued and outstanding can be voted at the annual general meeting, or receive dividends. Treasury stock is therefore like the shares being in limbo. They exist, but they don’t mean anything. The only advantage to keeping the shares in treasury is that if the company wants to sell them again, it can do so without having to issue new shares.

In all of these scenarios, the cash account is the only one that is not part of equity. All the others appear in the equity section of the balance sheet.

Shares Kept in Treasury

So, the first scenario is when shares are repurchased and kept in treasury. If that is the case, the bookkeeping entry is simple. Suppose the company paid $2,000 to repurchase the shares. The entry would be: DR Treasury stock $2,000, CR Cash $2,000. Treasure stock is a contra equity account, so it normally has a debit balance, even though the other equity accounts normally have a credit balance. The effect is to reduce the overall equity, but by using a contra account, the share capital account itself is unaffected. It still shows the entire value received from shareholders when shares were issued. Everything stays in balance, of course, because cash is reduced.

Shares Cancelled, Repurchase Price > Original Price

If the shares are repurchased and cancelled, or “retired,” they are no longer available for resale. The accounting for this depends on the price paid to buy back the shares. If the repurchase price was higher than the price at which the shares were originally issued, the entry will use up some retained earnings. Suppose that a company pays $6,000 for shares that were originally issued at $1000. The bookkeeping entry would be: DR Share capital $1,000, DR Retained earnings $5,000, CR Cash 6,000.

Shares Cancelled, Repurchase Price < Original Price

If the shares are repurchased and cancelled, but the repurchase price was lower than the price at which the shares were originally issued, the entry will increase the contributed surplus in the equity section. Recall that contributed surplus arises when shares are issued for a price that is higher than par value. We use the same account in this repurchase scenario.

Suppose that a company pays only $800 for shares that were originally issued at $1000. The bookkeeping entry would be: DR Share capital $1,000, CR Contributed surplus $200, CR Cash $800.

This is all quite technical, but the important thing to understand is the motivations of the company in doing a share repurchase. I’ve got a series of posts on Apple and its share repurchase strategy that you might want to read if you wish to think a bit more about this.

Employee Stock Options

Since we're talking about the equity of the company, let's talk about employee stock options. This is a very popular topic for MBA students.

An employee stock option is basically the right to buy shares at a set price. Companies issue stock options in order to align the interests of employees with the interests of the shareholders. Stock options incentivize employees to work to raise the share price of the company so that their stock options are worth more. At least, that’s the theory. Another way of getting employees to work in the interests of the company is to give them satisfying jobs with a living wage, but since stock options are most often issued only to senior management, we can take for granted that these corporate executives already earn a living wage.

Stock options assume that the executives are not going to work as hard or as well if they don’t have this big carrot dangling in front of them. Employee stock options are based on a very dismal view of human nature. But maybe with corporate executives, the view is justified. I don’t know enough of them to have formed a statistically robust opinion.

Features

There will be a number of features included in a stock option.

The most important one is the exercise price. That's the price at which the employee is entitled to buy the shares. If the market price of the shares is lower than the exercise price, the option is worthless. If the market price is higher than the exercise price, then the difference represents a gain to the employee, and this gain can be extremely lucrative.

The stock option will also specify a number of shares that the employee can buy.

There will be a vesting date, which is the date at which the employee can begin to exercise the stock option. Until that point in time, the employee basically has a piece of paper promising them the opportunity to buy shares at a certain price. The gap between the awarding and the vesting of the stock option presumably keeps the employees from collecting their stock option and immediately walking away from the company with a windfall. Stock options are an incentive, not a reward.

Finally, there will be an expiry date, some time after the vesting date. The employee has to exercise the stock option on or before the expiry date. It’s possible that the vesting date and the expiry date are the same, in which case the employee has to act on that date or forego the stock option. A gap between the two dates makes the stock option more valuable because the employee can, in theory, pick a date when the stock price is more favourable to them.

Sometimes stock options specify that the option can only be exercised on a specific date. In other cases, the vesting date and the expiry date will be different and the employee can exercise the option anytime between those two dates. That makes the stock option more valuable because it gives the employee the option of buying the stock if the stock is valued really high and is afraid the stock price might go down.

Accounting for Stock Options

When the employee does exercise the stock option, the company has to do a couple of things.

The first thing is it has to issue the new shares. This dilutes the position of the existing shareholders. When you see earnings per share (EPS) at the bottom of a corporate income statement, you’ll see the figure stated as basic and diluted. Basic EPS is the earnings of the company that year divided by the average number of shares that were outstanding during the fiscal period. (An average is used because the company may have issued or repurchased shares during the period.)

Diluted EPS is the same calculation, but with all the stock options that have been awarded to employees added to the denominator. That being a greater number, diluted EPS is smaller than basic EPS (except of course, in situations where no stock options have been awarded to anyone). The two figures are provided to signal to investors that their percentage interest in the company is going to go down if the employees exercise their stock options.

Once the company has issued the new shares, they don’t go onto the stock market, they go directly to the employee who is purchasing them. The company gets some money and the shares get transferred to the employee.

That sounds like a simple transaction. However, the exchange takes place at a lower price than the market price of the shares on the day. This means that the stock option is considered an expense to company, because the company has incurred an opportunity cost: it could have sold the newly issued shares on the market that day, but it handed them to the employee at a lower price.

This expense is recognized when the option is awarded to the employees, not when they exercise it. The company incurs a cost because of its own decision, not because of the employee’s decision. This expense has to be calculated based on the present value of the opportunity cost. The calculation takes into account not just the exercise price and the time between award date and the exercise date. It also has to include an estimate of what the share price will be on the exercise date, and of course, that is a mad science if the vesting date is far off.

The calculation also has to include an estimate of the likelihood of the stock option being exercised by the employee:

The employee might decide not to bother if the price is not attractive

The employee might not have enough money to exercise the option

The employee might die or leave the company before the vesting date.

The company has to make all these estimates and plug the likely cost into a discount calculation, to deal with the time value of money as we’ve seen before. Because there are so many factors a play and possibly many employees with stock options, an actuarial model would likely be built for this calculation.

One final thing to think about is this: any share repurchases by the company between the awarding of the stock options and the exercise of the stock options will raise the value of the shares on the market, because the same valuable company is divided up into fewer outstanding shares. This raises the value of the stock options, of course. So think about the fact that the decision to repurchase shares is highly influenced by senior managers and board members who own stock options. This would go a long way towards explaining why Apple, for instance, chooses to repurchase shares rather than simply pay dividends. Finance is complicated, especially when people are involved.

Accumulated Other Comprehensive Income

Another line that appears in the equity section of many balance sheets is “Accumulated Other Comprehensive Income” (accumulated OCI). This line is going to come up when we talk about investments in other companies. I also want to devote an entire lesson to other comprehensive income, to deal with things like hedges and foreign currency fluctuations, but for now, think of accumulated OCI like this. A company’s assets and liabilities will go up and down in value for many reasons. We normally expect that this occurs because of the business decisions of the company’s managers. They buy a truck and it gradually wears out. They take out a loan and then gradually pay it off. They sell some inventory and earn a profit. All of these changes are reflected in the income statement as revenues or expenses.

Sometimes, though, changes in value on the balance sheet are beyond the managers’ control. For example, the stock market can go up or down, changing the value of the company’s financial investments. Shifts in interest rates can do the same thing, if the company has invested in bonds. Currency exchange rates can fluctuate, affecting the value of the profit from a foreign subsidiary added into the company’s consolidated financial statements. While some of this volatility may well be part of the business model of the company — for example, a real estate company intentionally invests in properties, knowing full well that they don’t control what happens to real estate prices — other fluctuations are just “noise.”

Shifts in the value of assets and liabilities will have an immediate, arithmetic effect on equity, because equity is always the difference between total assets and total liabilities. As I said, normally, changes in asset or liability values show up on the income statement as revenues or expenses.

If we want the income statement to reflect only the financial performance of the company that was due to actions within its own control — and this is a big “if” but one that the accounting regulators have accepted — then we need a way to separate the signal from the noise.

That’s what “other comprehensive income” and “accumulated other comprehensive income” are all about. They are an invention of accountants designed to help investors tell how the companies are doing, independent of world events. I would argue that this is a bit of a fool’s errand, that companies operate in the real world and have to find a way to deal with everything that happens around them. Managers should make provision for changes in currency rates, for instance. Better managers will do this effectively, worse managers will not.

However, the accounting regulators have said that under certain conditions, companies are allowed to “park” some of the noise that arises from changes in their net asset values. An example would be if a company invests in a five year bond and intends to hold onto the bond for the entire five years, without reselling it to someone else. If that bond goes up and down in value on the financial markets, a gain in value would normally increase the company’s net income and a loss in value would normally decrease the company’s net income. But if the gain or loss is only going to be realized at the end of five years, goes the argument, why should changes in value in the interim be allowed to affect net income? Why not just keep it off the income statement until the bond is sold? By that time, the accountants argue, the bond may well have returned to its original value.

The solution that has been adopted, the method of keeping this noise off the income statement, is to create a separate statement called the Statement of Comprehensive Income. That statement takes the net income number and adds to it the other changes in net asset values that was not shown on the income statement. Those other changes are referred to as “other comprehensive income.” So, comprehensive income equals net income plus other comprehensive income.

Net income, as we know, gets added to the retained earnings line in the equity section of the balance sheet. We need another line in the equity section to keep track of the other comprehensive income. That’s what accumulated OCI is all about. It’s the accumulated effect of any changes in net asset values over the years that did not appear on the income statement.

If, on average, currency fluctuations and interest rate fluctuations even out over the years, accumulated OCI will not grow to be a big amount. That’s the theory, anyway. Certainly, some portion of OCI will eventually be recognized on the income statement. That five-year bond we talked about will eventually mature, and any pending “noise” in its value that is in accumulated OCI will be removed from there and transferred to the income statement as a gain or loss on the investment.

It’s all a bit curious and a bit arbitrary, isn’t it? Companies have to decide which investments will be treated in the “OCI” way and which will be treated in the normal “income statement” way. I think this just give managers one more tool to use to shape their financial results. But I’m a financial accounting skeptic. Accounting regulators seem to be more optimistic.

Non-Controlling Interest

Now I want to look at a very common line item on financial statements, called non-controlling interest.

These images are from the financial statements of Saputo, an international dairy company:

The bottom of Saputo’s income statement

The bottom of Saputo’s balance sheet

Here you've got the bottom portions of the income statement and the balance sheet, and both of them mention “non-controlling interest.” What does this mean?

On the income statement, the net earnings figure of $612,869 is taken and divided into two parts, $607,608 that is “attributable” to the shareholders of Saputo Inc., and $5,261 that is attributable to this thing called non-controlling interest.

On the balance sheet, the share capital, reserves and retained earnings are added together, and this subtotal is labeled “Equity attributable to the shareholders of Saputo Inc.” Then there is some more equity added, $67,633, that is labeled “Non-controlling interest.”

So let me explain this, because its a common enough thing to see and I want you to be clear about it. Non controlling interest arises when you consolidate the financial statements of a parent company and its subsidiaries. When the parent owns 100% of the shares of these subsidiaries, you will not see any mention of non-controlling interest, because the parent has full control. However, it often happens that a parent company owns less than 100% of the shares of the subsidiary. In other words, there is a minority shareholder of the subsidiary who is separate from the parent company.

Subsidiaries are not only those companies that the parent company owns outright, like that subsidiary of Apple where all of Apple’s intellectual property profits are parked, offshore and untaxable. Subsidiaries can be consolidated into the company’s financial statements when the parent owns as little as 50% of the shares. In fact, it is possible that the parent could own less than 50%, because IFRS 10 defines control in terms of financial returns, not share ownership: is the investor (the parent company) exposed to, or have a right to, variable returns from the investee, and does the investor have the ability to affect its own returns through its power over the investee? That situation certainly arises through control of the voting rights through share ownership in the investee, but it could arise in some contractual situations, too. IFRS very wisely leaves the matter of control open to empirical investigation.

The point of a consolidation is to add together the financial positions and the financial performances of all the companies that a parent company controls. When this includes companies where the parent owns less than 100% of an investee company, a minority portion of the profit of that investee, and the net assets of that investee, actually belongs to someone else. Yet the consolidation adds all the revenue, all the expenses, all the assets, and and all the liabilities of the investee into the consolidated statements. It does this because the purpose of consolidation is to measure the value of the assets and liabilities that the parent controls, regardless of whether it owns all of them, and to measure the financial performance that the parent has achieved through this control.

This leads to a problem. The shareholders in the parent company are not entitled to 100% of the profits generated by the consolidated assets and liabilities, and they do not have a residual interest in 100% of those assets and liabilities. A small portion of the consolidated profits belongs to someone else, the minority shareholders of one or more of the consolidated investee companies. That is the amount shown at the bottom of the income statement, $5,261 in the example shown. Similarly, a small portion of the net assets belongs to those same minority shareholders, $67,633 in the example shown.

It’s called “non-controlling interest” instead of “minority interest” because these financial statements are a story told from the perspective of the parent company. It’s saying that other people besides the parent company own an interest in some of those subsidiaries, but they don’t have a controlling interest in them. Only the parent company has a controlling interest.

Note that if the parent company has investments in other companies that do not give it control over those companies, the financial statements of those investees are not included in the consolidated statements. Those investments are accounted for in different ways, which we'll talk about in the lesson on investments in other companies.

So that's what that “non-controlling interest” line means on an income statement or balance sheet.

Summary

Let's take stock of what we've learned about equity.

We looked at the different kinds of dividends, cash dividends and stock dividends.

We discussed the notion of residual rights and how the two different types of shares, preferred and common, stack up against other claims on the company.

We went over all the things that a company can do with its shares besides simply issuing them, including stock splits, stock consolidations, and share repurchases.

We then looked briefly at employee stock options, why they can be so lucrative to senior managers, and how a company must account for the implicit expense involved in awarding stock options.

We took a quick look at accumulated other comprehensive income, or accumulated OCI. We’ll deal with that in more detail in another lesson, but we have already learned that it’s a way to isolate the income statement from some of the noise arising from changes in financial markets, interest rates, and foreign currency exchange rates.

Finally, we learned what the phrase “non-controlling interest” means on the income statement and balance sheet, and how it only arises through consolidation of subsidiaries that are not 100% controlled by the parent company.

Again, remember that word “consolidation” is used in two different ways in accounting. There is the consolidation of shares by a company, when it takes a whole bunch of shares of small value and consolidates them into a smaller number of shares that are each worth more. There is also the consolidation of the financial statements of a parent company and its subsidiaries, to create a picture of the economic clout of the parent company.

The purpose of this lesson was not to turn you into an expert, which is why we didn’t go into the technicalities of, for instance, how to value stock options. This lesson was just to help you feel confident that if someone were to put a balance sheet in front of you, point to a line in the equity section, and ask "What's that mean?”, you’d be able to explain it in basic terms.

When you are ready to learn more about the technical accounting behind these terms, head on into the next lesson. Thanks for reading!

Title photo: Amsterdam, where pedestrians, cyclists, transit, and cars are all treated equitably.