Long-term liabilities are the financial obligations that a company does not expect to settle within the coming fiscal year. This time factor makes a huge difference in how to account for these liabilities, because the ability to hold off paying a debt can be so important to the survival of a company.

There's a lot to cover in this lesson, so I want to take things a little bit slowly and make sure we understand the basics. I'm going to go over some fundamental principles of long-term liabilities, and then the basic bookkeeping for standard debt situations. Then I'm going to be talking about more complicated situations, such as debts with matching assets and various miscellaneous obligations. Finally, we’ll return to the topic of hybrid securities that we’ve touched on in a previous lesson.

Fundamentals of Long-term Liabilities

So let's look at these fundamental principles. I want to start with the time value of money, and then I'll talk to you about the cost of borrowing.

The time value of money is a really basic concept for understanding debt. And I can explain it by comparing it to interest:

On the left hand side of this figure is a chart that shows interest. You've got a thousand dollars being invested at 7% interest in Year 0, and over time it grows to almost $2,000.

(This is a very useful graph to remember, by the way. At 7% interest, the value of an investment roughly doubles in 10 years. At 10% interest, the value would roughly double in 7 years.)

On the left, time progresses from left to right and the value of the investment grows. Discounting is the opposite situation. Imagine that you have to make a fairly big payment sometime in the future. What is the value of that payment in today’s terms?

Think about it. If you have to make a big payment in 10 years’ time, you have lots of opportunities to save up for it. It's not the same impact on your finances as having to make the same payment today. How would we calculate today’s value of that future payment? Well, we just take the interest calculation and we turn it upside down. Instead of moving from left to right through time, we work backwards from that future date, dividing instead of multiplying, to come up with a present value. In other words, if you have a payment of $2,000 due in 10 years, and you discount it at 7%, you're going to come out with a figure of approximately a thousand dollars.

With interest, you can easily calculate how much an investment of money today will be worth at some date in the future With discounting, you are just “calculating interest” backwards. Whether you expect to pay or receive a sum of money in the future, you can figure out what that sum is worth today. In others words, you can calculate the effect time has on the value of money.

Discounting is therefore a vitally important tool in debt situations, particularly for notes payable, bonds, and pension plans where the cash flows may be many years down the road. I'll be showing you how discounting calculations affect each of these kinds of liabilities in this lesson.

Interest

Calculating interest involves three variables:

The number of periods. In the example we just graphed, it was the number of years, but you can do the calculation in terms of months.

The interest rate per period. The important thing here is that if your number of periods is in months, you have to convert the annual interest rate to a monthly interest rate.

And of course, you need to know the amount that's invested.

The formula takes the principal and multiplies it by the formula shown, which is one plus the interest rate, r, all to the nth power. In the example that we graphed, you started with a thousand dollars. The interest rate was 7%. So r was 0.07. Take the thousand dollars and multiply it by 1.07. In the second year, multiply the result by 1.07 again. In the third year, you multiply that result by 1.07. With a calculator or spreadsheet, you’d calculate the value in Year 3 as the principal multiply it by 1.07 cubed, or 1.07 to the third power.

In the example shown here, the thousand dollars is invested at 5%. So, that’s a thousand dollars times 1.05 cubed. The future value of $1,000 over 3 years, at 5% interest, is $1,157.63. That’s how much you’d end up with in three years.

Discounting

With discounting, as I said, you're working the opposite direction. The variables are roughly the same, though. You've got the number of periods, and instead of an interest rate, you've got what's called the discount rate. That’s just what we call an interest rate when we're working backwards. And of course, you've got the amount that you are either going to receive or pay at the specified point in time in the future.

The formula is very similar to the interest formula, except that instead of multiplication, you're using division. The present value is the amount of the future cash flow, P, divided by one plus r to the nth.

In the example shown, you have a thousand dollars to be received or paid in three years time. Discounting this at 5%, you're going to get $1,000 divided by 1.05 cubed, which is $863.84.

Now, just to compare here, if we had set P equal to $1,157.63 and plugged it into this formula, the answer would've been exactly $1000. It’s the same calculation as interest, but in reverse.

We’re going to be returning to the discount calculation later in the lesson, but first, let’s talk about an underlying accounting issue for long-term liabilities, the cost of borrowing.

Cost of Borrowing

The cost of borrowing money is not simply the interest you pay. At least, not if you are a corporation. I want to show you how income tax plays into corporate decisions on whether to borrow money.

We’re going to be calculating the impact on our net income of borrowing money to purchase a new asset. We’ll be comparing this to the option of issuing new shares in order to raise the funds we need for the new asset. If we borrow money, we need to pay interest. If we issue new shares, we don’t.

Let’s assume that our interest rate is 6% and our corporate tax rate is 20%.

We also need to assume how good we are at generating new revenue with our assets. That’s called the asset turnover ratio, and we’ll set that at 1.20. That means that for every $1 of assets, we generate $1.20 in revenue. For the sake of our model, we’ll assume that this holds true for any new assets we invest in.

We’ll need an amortization rate for the new asset, so let’s say that’s 20%. (I’m going to use the word “amortization” throughout this lesson because that covers both tangible and intangible assets. If we knew for sure we were talking about a tangible asset, it would be more common to use the word “depreciation.”)

Finally, we will need to know what our gross margin is, so that we can see the impact of all that new revenue on our taxable income. Let’s set the gross margin at 30%.

Baseline Scenario

Let’s walk through the three scenarios shown in this figure, starting with the base case. Before we do anything, our hypothetical company is entirely funded by $1,000,000 in equity. We have no debt, so we have $1,000,000 in assets.

With an asset turnover ratio of 1.2, we generate $1,200,000 in revenue.

With a gross margin of 30%, that gives us a cost of goods sold of $840,000 and a gross profit of $360,000.

I have assumed, in all the scenarios, a fixed operating cost of a $100,000. Our amortization expense is going to vary, however, because that is determined by the amount of assets we've got. So in the base case, we've got a million dollars worth of assets at an amortization rate of 20%, so that means we've got amortization expenses of $200,000.

Now, there's no interest expense in this scenario because we have no debt, so that leaves us with a taxable income of $60,000. Income tax on that, at our assumed tax rate of 20%, will be $12,000. All of this leaves us with a net income of $48,000, a 4.8% return on our million dollars worth of equity.

That is the baseline scenario. In the next two scenarios, we will be adding another half million dollars worth of assets. Those assets have to be financed in one of two ways, either through equity or through borrowing. Let’s compare these alternatives.

Equity Scenario

In the equity scenario, we’ve issued another half a million dollars worth of common shares and invested the proceeds in new assets. This scenario is going to be similar to the baseline scenario, except that with additional assets, our asset turnover ratio of 1.2 means that we're now going to generate $1.8 million of revenue.

Our gross margin of 30% means that cost of goods sold rises to $1,260,000 and gross profit rises to $540,000.

Fixed operating costs remain at $100,000 because they are, as the name implies, fixed.

Amortization expense has gone up now because there are more assets. We now have $1.5 million worth of assets, so amortization expense is 20% of that, or $300,000.

This gives us taxable income of $140,000. Our tax rate of 20% puts our income tax expense at $28,000, leaving us net income of $112,000.

So this makes sense, right? We’ve added new assets and generated more revenue. Our additional revenue was reduced by an increases in cost of goods sold, amortization expense, and income tax. The $500,000 worth of new equity has increase net income dramatically from $48,000 to $112,000.

This is great because we’ve increased our return on equity from 4.8% to 7.5%. Very nice. This is all possible because our sales are profitable and because some of our costs are fixed, and don't go up when we invest in additional assets.

Long-term Debt Scenario

Now let's compare this to the third scenario, where we invest the same amount in new assets, but we fund this by borrowing instead of issuing new shares.

The additional $500,000 of assets is going to produce the same revenue, the same cost of goods sold, and the same gross margin as in the equity scenario. We'll also have the same fixed costs and the same amortization.

The difference is that we now have $30,000 worth of interest expense. That comes from the fact that we borrowed $500,000 and our interest rate is 6%.

Here is where things get interesting, if you don’t mind the pun. Because of the interest expense, our taxable income is $30,000 lower than in the equity scenario: $110,00 instead of $140,000. This means that at a tax rate of 20%, our income tax expense is only $22,000, compared to $28,000 in the previous scenario. This leaves us with net income of $88,000. This is considerably lower than the $112,000 of net income that we had in the equity scenario.

So, borrowing sounds like a terrible idea!

You have to remember, though, that our shareholders didn't have to put more of their own money to get the new assets. The new assets were funded by someone else. We paid our lenders interest for the privilege of using their money, lowering our net income, but our return on equity is actually higher! It now stands at 8.8%, better than the 7.5% in the equity scenario.

We're generating an $88,000 profit out of $1 million in equity, rather than $112,000 from a $1.5 million investment. The return is lower in absolute terms, but in percentage terms it is higher. That’s why borrowing is attractive. The word for this in finance circles is leverage. We’ve leveraged the shareholders investment by borrowing to generate a higher rate of return.

Why does this work? Well, let’s just think about it. The additional $500,000 of assets has generated $600,000 of additional revenue ($1.8 million compared to $1.2 million in the baseline scenario). After deducting the cost of goods sold, we’re left with additional gross profit of $180,000 ($540,000 compared to $360,000 in the base case scenario). Then we’ve got our fixed operating costs of $100,000 and our increased amortization expense of $300,000, leaving us $140,000. So far, this is identical to the equity scenario. Now, if we were to deduct all the interest ($30,000) as well as the same income tax expense as the equity scenario ($28,000), we’d still be better off than in the baseline scenario. Our net income would bee $140,000 - ($30,000 + $28,000) = $82,000. That’s an 8.2% return on our million dollars of equity, better than the 4.8% we earned in the baseline scenario, all because of our asset turnover ratio of 1.2 and our gross margin of 30%.

It gets better, though. Our interest expense is tax deductible, so after deducting the $30,000 interest expense, income tax is calculated on only $110,000 of taxable income, rather than $140,000 as in the equity scenario. This means our income tax expense is only $22,000 instead of $28,000. Net income is therefore $140,000 - ($30,000 + $22,000) = $88,000, giving us the 8.8% return on equity that we calculated in debt scenario.

Because the $30,000 interest expense reduces our taxable income, it generates tax savings of $6,000. This means that the after-tax interest expense is only $24,000.

Quite bluntly, what this means that the other taxpayers in our country are picking up part of the cost of our borrowing. Instead of paying 6% interest, we effectively enjoy a tax-subsidized interest rate of 4.8%. What a great deal! For us, I mean. It’s not a great deal for those taxpayers, unless our profits contribute to society in such a way that they benefit indirectly.

That might happen. It’s completely possible that the profits we earn will be reinvested in the company and lead to new hiring, increase wages, increase orders for our wonderful suppliers, etc., etc. It’s also completely possible that those profits will be paid out to shareholders who will move the money to the Cayman Islands and never pay tax on it. Either way, tax subsidization of corporate borrowing is a real thing.

What can we conclude? That borrowing is a great idea as long as one condition holds: the rate of return on the additional assets you purchase has to be higher than the interest rate. Here, the interest rate was 6%. If the additional assets are not going to generate at least a 6% return, there's no point in borrowing because we're actually going to come out behind. Thankfully, our pre-tax return on assets is higher than the interest rate. On $500,000 of additional assets, we’ve generated an additional $80,000 (that’s $600,000 of revenue less $420,000 cost of goods sold and $100,000 of amortization expense). That is higher than our $30,000 interest expense, which is what makes the borrowing worthwhile. If the interest rate had been higher or our pre-tax return on assets was lower, we might have been worse off. Maybe even much worse off.

And this is the effect of leverage. Leverage amplifies good results, but it also amplifies bad results. So if your return on assets is lower than your interest rate, you shouldn't borrow because you are only going to make your situation worse.

Those are all the calculations you need to understand in order to get into accounting for long-term debt, so let's start to look at that now.

Recording Interest on Debts

The main thing you need to remember in accounting for debts is that interest expense and interest paid are two different things. Interest is accrued as a function of the passage of time. As time goes by, you will owe interest on your debt whether or not you pay the interest to your creditor. An accrual is an adjusting entry that's done at the end of the accounting period, and we've already done adjusting entries in our bookkeeping examples earlier in the course.

Interest is what's called a period cost because it pertains to the period for which you are doing the interest calculation. It’s doesn't have anything to do with a specific performance obligation, so it doesn’t have to be matched to when you recognize revenue on any particular sale.

The journal entry shown here, to record the interest expense, therefore occurs regardless of when you pay the interest to your creditor. You've got a debit to interest expense and a credit to interest payable.

The disclosure of the loan on the balance sheet is going to be basically at the value of the remaining principal on the loan that's yet to be paid, plus any interest that has been accrued and is payable. So that's what's going to show up on the balance sheet.

And keep in mind of course, that when you actually get around to paying the interest, it's not an expense because you've already recognized the expense on the income statement. Instead, as shown here, you debit the interest payable that you set up with the accrual entry, and credit cash. (If you had not accrued the interest previously, this would simply be a debit to interest expense, credit to cash. There is no need to have a separate accrual transaction if the interest is paid on the same day as the end of the fiscal period.)

The other thing to keep in mind when accounting for debts is that interest and principal are two different things. Here we have only talked about accruing and repaying interest. The principal of the loan has not been affected. When you actually repay principal, that is not an expense, it’s just a reduction in assets (credit to cash) and a reduction in liabilities (debit to the loan liability). The income statement is not affected. This makes sense because obtaining a loan is not revenue, it’s incurring a liability. Similarly, repaying a loan is not an expense, it’s retiring a liability.

Interest-free Loans

An interest-free loan is just an IOU. Imagine someone benevolent, like your father-in-law lends you a million dollars to start up a business and expects to be repaid the million dollars in three years’ time. That’s a very nice deal for you, but it raises some accounting issues related to the time value of money. The amount you get today is worth more than the amount you will repay in three years, because of the passage of time. You receive a million dollars, but you incur a liability that is less than a million dollars because you don’t have to repay the money right away.

What is the present value of that million dollars that's due in three years time? Well, this is where our discounting calculation comes into play. Let’s assume that the prevailing interest rate is 5%. That’s the interest rate you would get if you borrowed from the bank instead of getting the money interest-free from your father-in-law. The present value of the million dollars, discounted at 5% for three years, is $863,838. What should you do with the difference between the million dollars and the present value? You record it as a gain on the income statement, because you have benefited financially from this arrangement.

Next year, you're going to do a present value calculation again, and because you will only be discounting by two years, the value of the note has changed. It has gone up to $907,029. To account for this, you need to credit the note payable account by $43,192 to raise it to the new value. (There is a $1 rounding error here, which we’ll just ignore.) The corresponding debit goes to the income statement as an interest expense.

And of course, in the following year, we're going to discount it only by 1.05, so the value of the liability will go up again, and the year after that, we won’t discount it at all, so the final value of the liability, at the time you repay the money, will be exactly $1,000,000. Hopefully you’ve managed to set aside the money to pay that off, otherwise you’re going to have a rather embarrassing conversation with your father-in-law. I’m not speaking from personal experience at all. Definitely. (Thankfully, it was only a $7,000 loan. I eventually managed to repay the debt.)

Debts with Matching Assets

Frequently when a company takes on debt, they are using the money to purchase an asset. In fact, often the debt might be secured by the asset, as a condition of the financing.

There are three such situations that I want to explore with you: mortgages, leases, and pension plans. Let's go through them in order.

Mortgages

Mortgages are just a loan where you make equal payments, called blended payments because the blend together the payment of interest with the repayment of the entire principal that you borrowed.

The scenario here is that you're purchasing price an asset for $1 million dollars. Generally, banks don't like to lend you the whole purchase price, because they want you to have some skin in the game, so I'm going to assume that you're making a down payment of $100,000.

The bank is charging you 5% interest on the loan, and you're going to pay it off over five years. Now, to simplify things and cut down on the number of rows I need to display, I’m going to assume one big blended payment per year rather than 12 smaller blended monthly payments. Most mortgages are monthly, of course, but the calculations of interest and principle are conceptually identical to what you would see if I were showing monthly payments. We’ll just have larger payments in order to pay off the entire mortgage in five payments.

Given the purchase price of the asset ($1 million) and your downpayment ($100,000), the mortgage will be $900,000. Using Excel to calculate blended payments on this at 5% interest, we get five equal payments of $207,877. That takes care of the interest that is charged each year on the outstanding balance of the loan, and it gradually pays down the principal so that at the end of five years, you will have paid off exactly $900,000 of principal.

Looking at the left side of this figure, the first year’s interest on the initial $900,000 balance is $45,000. You could have done that calculation in your head. It means that after paying the interest, you have $162,877 of your $207,877 payment left over to be applied against the principal. That leaves a balance after one year of $737,123.

In the second year, Excel tells us that 5% interest on the outstanding balance is $36,856, quite a bit less than the first year’s interest. You make the same payment as you did at the end of year 1, but now after the interest is paid, there is more left over to pay off the principal. At the end of year 2, then, the loan balance is down to $566,101.

The following year, interest on that balance is even lower than the year before, leaving you even more to use to pay off the principal, bringing the principal down to $386,529. Of course, the interest expense keeps dropping because the interest rate remains at 5%, but it is being charged on a smaller and smaller loan balance. The amount that's left over out of the fourth $207,877 payment is therefore bigger than ever, leaving a balance of $197,978. By the time you get to year 5, the interest on $197,978 is just shy of $10,000. The interest and the remaining balance add up to exactly the amount of your regular loan payment. This leave a balance of zero at the end of year 5, and the loan is done. You can see from the balance column that the liability goes down and down and down until it is paid off. That is what you’d expect. It’s important to look at the interest column, though, too, because you can see that the interest expense also keeps going down. The cost of borrowing is lower and lower because you owe the bank less and less.

This is not the only effect on the income statement, though, because you purchased an asset that needs to be depreciated or amortized. In this example, I chose a straight-line amortization policy, which means that the amount to be amortized (the purchase price minus the residual value of the asset at the end of its life) will be expensed in equal amounts over the life of the asset.

I’ve also chosen to amortize the asset over 8 years. This decision would be based on how long the asset is expected to last. It has nothing to do with the length of the bank loan.

These policy choices give you amortization expenses of $106,250 each year, until the book value is reduced to $150,000, at which point we stop. You will have amortized $850,000 of the asset value, with eight equal amortization expenses.

The reason I’m showing you this is that when you are making decisions to purchase an asset and finance it with debt, you need to consider the overall effect your decision will have on your income statement.

The first year, you have $151,250 of amortization and interest expenses. The total expense will then decline over the first five years as the loan gets paid off, levelling out in year 6 at $106,250, and continuing on at that amount for another couple of years.

Different amortization policies would lead to different distributions of the expense over the life of the loan and the asset. The ability to chose amortization policies gives managers considerable influence over their financial results.

Leases

Let's turn our attention to leasing now. I want to compare leasing to two other options, which are renting and purchasing.

The basic idea of renting is that all you are purchasing with your monthly payments is the right to use something. If it’s an apartment, you do not own the apartment as a renter, but you do have the legal right to use it as your home. The apartment is owned by someone else, but you are the one who gets the practical benefit of it. In exchange, the owner gets your rental payments.

Leasing is just like a rental agreement, except that you are making a commitment to rent something for an extended period of time. Under IFRS, if the lease is less than 12 months, you just account for it as rent. There is no other implication other than the idea that you are renting something from its owner. Your rental payment is simply recognized as a period expense. The only benefit of the lease is that you, as a renter, have guaranteed access to the apartment (or truck or whatever else you are leasing) at a fixed monthly cost, and the owner has stable cash flows because they won’t have to find another renter if you decide to move on.

The other scenario to compare leasing to is purchasing. If you purchase a condo apartment or a truck or whatever, you get ownership of the asset and all the risks and rewards that come from that. As you know, it is common to take out a loan to purchase the asset.

All of this seems very straightforward. Leasing is just like renting, and nothing like purchasing. Right? Well, the problem is, what happens when the length of the lease extends to the point where you are getting use of the asset for pretty much its entire useful life? If you lease a truck for 8 years that is expected to last 8 years, your situation is no different economically from taking out a loan and buying it yourself. Yet if you account for this as rent, you have created a situation called “off-balance sheet financing.” You have no asset and no debt on your balance sheet, even though in economic terms you are paying a finance company for 8 years and owning the truck for its entire life.

This kind of accounting makes it difficult to compare companies that borrow and purchase from companies that lease. It makes the companies that lease look less risky because they have lower debt on their balance sheet, even though economically their situation is indistinguishable from companies the borrow and purchase.

To level the playing field, so to speak, and allow people to compare these two kinds of companies fairly, IFRS requires long-term leases to be treated as long-term liabilities with a matching asset, very similar to the mortgage situation we just discussed.

Naturally, this raises the question of what constitutes “long term” for a lease. The International Accounting Standards board has made the decision, with IFRS 16, that any lease shorter than 12 months should be treated as rent, and any lease longer than 12 months should be treated as long-term debt with a matching asset. I’ll show you how this calculation works.

As we saw with the interest-free loan, any payment in the future can be discounted back to present value. A lease involves a whole series of regular payments, but if you discount each of these payments back to the present value at the beginning of the lease, you can add them up to calculate what the total financial value of these obligations is — because that’s what these are, they are obligations to make regular payments to the leasing company. This total financial value needs to be set up as a liability, just like we did for the interest-free loan. (Note that unlike the interest-free loan example we discussed, there is no “gain” to worry about. Leases are not interest-free. The interest is built into the monthly payments.)

So where is the asset? Well, it’s intangible. What you get when you sign a lease is the right to use the asset for the duration of the lease. That is the asset you need to show on your balance sheet. The initial value of this asset is assumed to be exactly the same as the initial value of the lease liability.

Once you set these values up on the balance sheet, a right-to-use asset and a lease liability, you proceed as if you had taken out a loan and purchased an asset. You know your blended payments on the loan — they are the lease payments that you have agreed to — so you only need to choose an appropriate amortization policy. We’ve seen all this before in this lesson, so I don’t have to show you what it looks like.

So, even though you don't legally own the asset, from an accounting point of view, a long-term lease is treated as if you owned it. The only conceptual leap here is that you take the present value of all the lease payments and use that figure as the initial value of both the financial liability and the intangible “right-to-use” asset. Once you’ve done that, it’s just like having taken out a mortgage to buy the asset.

Pension Plans

Pension plans are another situation where you've got an asset and a liability that match each other. How does this arise?

First of all, you have to realize that there are two different kinds of pension plans. The simplest one is the defined contribution plan. With a defined contribution plan, the employer commits to contributing a specified amount — a “defined” amount — every pay period. (Of course, this assumes that you're fortunate enough to have a job that pays you pension benefits.) The company deposits a certain amount of money into your pension plan, which is shared with all the other employees. The pension plan will be operated by an independent trust company. “Trust” just means that the trust company accepts the obligation to act in the best interests of the beneficiaries of the trust. It does not act in the interest of the employer.

With very large employers, the trust company may have been set up expressly for the purpose of managing the company’s pension plans. With smaller employers, the trust company will manage pensions on behalf of multiple employers, presumably achieving some costs savings as a result.

With any pension plan, the contributions are held in trust for you until you retire. The important thing about a defined contribution plan is that once the contribution is made, there is no future obligation for the company. The benefit that you get when you retire will be determined by the performance of the investments that are made by the trust company. If the investments have done well, you're going to end up with higher pension benefits when you retire. If the trust company has not done a good job of investing, or if the economy hasn't done well, then the amount of your pension benefit is not going to be as high.

This means that once the employer makes the defined contribution, it is absolved of any future risk. All of the risk is yours. You are the one that gets the bigger or the lower benefit in the future, depending on how the investment has done financially. Your employer is not on the hook for any shortfall.

Defined contribution pension plans expose all of the individual employees to market risk, which is something they can't control. It’s important to realize that defined contribution plans are designed expressly to pass on financial risk from employers to employees.

With a defined benefit plan, you have quite a different situation. The pension contract between the employer and the employees, usually represented collectively by a union, will stipulate that the employee will receive a specific amount — a “defined” amount — upon retirement. For instance, rather than the contract saying the company must contribute $250 every month into your pension plan — that's the defined contribution scenario — the contract will say that when you retire, you will receive a certain amount of money, say $1,500 a month or $2,500 a month. This amount will typically depend on how long you worked for the company and how much you earned.

Given this future obligation, the company has to estimate, with the help of actuaries, how much it needs to set aside in trust in order to satisfy the obligation. This involves predicting the future pension benefit payments: how long does it expect its employees to work before they leave or retire, how much does it expect to pay them in wages during that time, how long does it expect them to live after they retire. (You can see immediately how macabre pension accounting is. If you die soon after retiring, that’s good news for the pension fund because you no longer collect benefits.)

Having projected all these pension benefit payments, What the company discounts them to their present value. That’s the pension benefit obligation, and it will fluctuate quite a bit for two reasons. One is that the assumptions will change from time to time. Healthcare improvements might mean that pensioners will be expected to live longer, for instance. The other reason is that the payment of pension benefits to retirees is so far off — sometimes decades into the future — that any minor change in the discount rate will have a huge impact on the present value calculation.

In this table, I sketch out three scenarios where the company has to pay $1 million in pension benefits every year starting this year and continuing for the next 50 years. That’s a total cash outflow of $51 million.

At a discount rate of 4%, the present value of all those cash flows is over $22 million. If the discount rate increases to 5%, the present value drops to just over $19 million. If it increases to 6%, the present value drops even further to less than $17 million. That’s almost a $6 million decrease, caused only by the discount rate.

This happens because those last few payments are so far off in the future. You can see in the row for Year 1 that the impact of the discount rate is only bout $18,000. If you look at Year 50, though, the impact of the different discount rates is almost $90,000. And those amounts in Year 50, even at the lowest discount rate of 4%, are much, much smaller than $1,000,000. This is the effect of the time value of money, and it shows the dramatic difference a change in discount rate makes over the decades. When you think that some pension funds are valued in billions of dollars, a small change in discount rate will create a massive change in the present value of the pension obligation.

This used to provide corporate managers with considerable ability to manage the company’s earnings. They used to have some latitude in choosing their discount rate. Under IFRS, they are now expected to choose a rate that matches the yield on “high quality corporate bonds.” That’s much better than allowing managers to pick a discount rate out of the air, so to speak, but it’s still vague enough that it leaves a bit of wiggle room for managers.

Pension regulations have made it mandatory in most countries for employers to set aside enough money now, in trust, to meet the projected pension obligation. Before the advent of these regulations, employees could reach retirement age only to find that their employer was bankrupt and could not pay the promised pension benefits. Setting aside the necessary funds in trust has solved this problem, but it has also led employers to stampede in the direction of defined contribution plans, to avoid being on the hook for pension benefits. It turns out, corporations don’t like taking responsibility.

What you see on the balance sheet for a define benefit plan is the difference is between the financial assets that have been set aside in trust, and the present value of the projected pension benefits. These can both be huge amounts, so any change in either of them can result in a material impact on the income statement. Pension accounting regulations used to allow companies to smooth this out in various ways. I’ve published an article on this topic, from which the name of this website was taken. Nowadays, accounting regulations don’t allow companies to smooth these fluctuations out, leading to more accurate assessments of the value of the company’s assets and liabilities, but a noisier income statement (due to the impact of the pension fluctuations). Given that defined pension plans are less and less common as corporations successfully pass on financial risk to employees, you don’t see them as often as you did back in the 1970s and 1980s.

What does an employer receive in exchange for these promises of future benefits? Well, it receives the opportunity to pay its employees less, because the employees have agreed to a lower payment of wages now in order to receive the pension obligation. This is something that you have to keep in mind with pensions. They are deferred compensation. Employment law in the US, Canada, the UK, and elsewhere has long recognized this characterization of pensions. The employees have agreed to take lower wages now in exchange for future payments and other benefits — perhaps more job security, perhaps current healthcare benefits. The company is regarded as having negotiated this deferral of compensation and is responsible for paying it. It is not a gift to employees for years of faithful service, as companies used to pretend back when my grandfather had his employment terminated just weeks before retirement.

The main difference between the two kinds of pension — defined contribution plans and defined benefit plans — is who bears the risk. Is it going to be the individual employees or is it going to be the employer? With a defined contribution plan, the employer’s obligation is discharged on pay day. With a defined contribution plan, the employer has a very long-term obligation, and it also, as required by pension regulations, must have a long-term financial asset to match.

Other Long-term Liabilities

Having looked at three kinds of long-term liabilities that have matching assets, let's look at some other obligations that are also long-term, in the sense that they extend beyond the horizon of the next fiscal year, but which are much easier to understand. I want to discuss provisions, contingencies, commitments, and subsequent events. These are all terms that you need to be familiar with so that you can talk intelligently about financial statements that you come across at work.

Provision

A provision is an accrual that's made for a probable future obligation that has arisen because of some past event involving the company, but where there is uncertainty about the amount or the timing of the future economic outflow that will be required to settle the obligation. The word “probable” is important, because it if it is not probable, the obligation will be classified as a contingent liability, not a provision.

Provisions would be made, for example, for an obligation to pay future income taxes, to clean up environmental damage caused by the company, or to provide warranty services to customers.

With a provision, you must estimate the present value of the future economic outflow, recognize that amount as an expense now, and set up a corresponding liability. That means a debit to expense and a credit to the liability. When the obligation is eventually settled, there would be a credit to cash or some other relevant asset, and a debit to the provision liability; there would be no impact on the income statement at that time, except for the amount by which the provision that had been set up exceeded or fell short of the actual cost. If the company could magically predict the future, the provision would be exactly what was needed, but of course, this doesn’t happen in practice.

Another example of a provision would be where a company has been sued and it is probable that they are going to lose the lawsuit. The company may not know exactly the amount that is going to be awarded to the plaintiff, and it may not even be 100% certain that its going to lose. However, the company can still estimate the present value of the loss. It can say, "Well, we think we've got a 60% chance of losing the lawsuit, we expect the damages to be between $1.0 and $1.2 million, and we expect the suit to be decided in about two years’ time." The company would therefore accrue a liability by taking some suitable midpoint between the two figures, calculating 60% of that because of the 60% expectation of losing, and discount the result by two years, just as we’ve done in previous discounting examples. That’s the liability and the expense that will be accrued.

Each year, if the lawsuit hasn't been settled, the company would reevaluate the likelihood of losing the lawsuit, the likely damages, and update the provision. Any change in the value of this liability will mean a corresponding impact on the income statement.

Roughly the same procedure would be used by a mining company that is obliged to clean up its mine site after it is finished depleting it. Similarly, as we’ve seen, companies will estimate future warranty costs and loyalty program costs. To the extent that these extend beyond the horizon of the next fiscal year end, they will require the company to disclose long-term liabilities on the balance sheet.

All of these examples involve previous revenue-generating activities of the company — even the lawsuit, which presumably arises because of something the company has done in the course of business. That’s why the company is required to recognize the expense for these future obligations now. It’s the matching principle in action.

Provisions are a rather glaring example of an opportunity for managers to influence their company’s financial results. Because they involve predictions of the future, provisions depend on private knowledge that even an auditor may not be able to verify. All an auditor can do is question the managers and ensure that the reasons for a provision, or a change in provision, are plausible. It is always worth questioning not only the amount of a provision, but the timing of it. Ask why a company has decided to create a provision this year, instead of some other year. Who stands to gain from this timing decision? Whose reputation is enhanced or damaged by the creation of a provision? Sometimes you will find that the previous CEO is being blamed for losses related to a provision.

Contingencies

Contingencies are a financial obligation where it is not probable that the company will have to pay anything, or where it is impossible to estimate the present value of the obligation. Assuming that the possible economic outflow is material, and that there is more than a remote possibility that the obligation will have to be settled, contingencies are described in the notes to the financial statements. That’s all. Contingencies are not disclosed as liabilities on the balance sheet and no expense is recognized. If events should transpire to make the financial outflow probable, then the contingency would have to be changed into a provision.

A lawsuit might fall into the category of a contingency, for instance, if the company has no idea what the outcome is going to be, or if the company feels it is probable that it will win the lawsuit.

Commitments

Commitments are future economic outflows that will arise because of contracts the company has entered into. In this case, there is nothing for the company to do but disclose these in the notes. The company should describe the nature of the commitment, try to quantify it where possible, and outline the circumstances that will determine the amount.

For instance, a company would disclose in the notes its purchasing agreement with a supplier if it has agreed to make certain minimum purchases. Nothing needs to be accrued in advance, but this disclosure helps readers of the financial statements to understand that some of the company’s economic resources are spoken for.

Subsequent Events

Subsequent events are not liabilities, but I like to add them into this section of the course because the are a bit like contingencies and commitments: the depend on events that happen after the date of the financial statements. These are events that occur after the year-end, so subsequent to the date shown on the financial statements, but prior to the publication of the financial statements.

There are two kinds of subsequent events that matter here. The first is when something happens after the year-end that causes you to adjust the estimates you are using to create provisions or allowances. If this happens, all you need to do is adjust the estimates using this up-to-date information.

For instance, in your allowance for doubtful accounts, you may worry that a customer may be going bankrupt and include an allowance for the possibility of not getting paid. Just before you publish the financial statements, you find out that the customer has actually filed for bankruptcy and you now know for certain that you are not going to get paid. You can update the allowance accordingly. Alternatively, perhaps the customer surprisingly pays you the amount owed. If you had included that amount in your allowance for doubtful accounts, you can take it out and adjust the amount you show for accounts receivable accordingly. This does not change the amount owed to you at the year end, because at the year end the customer still owed you the money. However, receiving the bad news or good news about the customer will change your estimate of the value of your accounts receivable on the date of the year end.

Same thing if you make a provision for a lawsuit. If the lawsuit settles one way or another between the year-end and the publication of your financial statements, or if there is a major development in the case that changes your beliefs about the likelihood of losing or the likely damages that will be awarded, you can update your estimate and adjust the provision accordingly.

The second kind of subsequent event is one that does not impact your year-end financial results, but it is something that readers of the financial statements need to know. For example, what if there was a major fire in your factory two weeks after the year end? The value of the factory at year end is unaffected by the fire, but readers really deserve to know that the factory is no longer an asset. Subsequent events like this are simply disclosed in the notes to the financial statements.

Subsequent events might include a decision after the year-end by the board of directors to repurchase shares or issue dividends. Perhaps you've been awarded a major new contract, which would be positive news. Readers need to know this kind of thing in order to evaluate the meaning of your year-end numbers, even though these events don't actually change the numbers themselves.

Hybrid Securities

Finally, I want to talk to you about hybrid securities. These are bonds (liabilities) that may have features that make them behave more like equity, and preferred shares (equity) that may have features that make them behave more like liabilities.

Bonds

A bond is a debt that's issued by the company. A bond will specify a term, such as six months or three years, at which point the debt will be repaid. A bond will also specify an interest rate on the debt. The company that issues the bond will pay interest on a regular basis to the bondholders during the term of the bond, and at the end of the term will pay the bondholders the face amount of the bond. The face amount is basically the principal of the loan. Unlike a mortgage, the payments on a bond are interest-only. These are not blended payments; no part of the principal is repaid until the end of the term of the bond.

The value of the bond is the discounted value of all those future cash flows, interest and principal included. The calculation of the price of a bond depends on the discount rate that is used, and this rate will take into account not just market interest rates, but the riskiness of the company issuing the bond. A bond from a reputable company is going to be worth more than a bond from a company that might go bankrupt, and therefore people are willing to pay more for the bond from the reputable company. The price calculation is going to take all these factors into account.

A debenture, by the way, is simply a bond that is not secured on any assets of the corporation. This si a term that you'll hear thrown around when people are talking about bonds. Bonds are often issued with an explicit lien on some of the issuer’s assets. Debentures are not, they are just unsecured debt, and are priced accordingly. Bonds and debentures are accounted for in exactly the same way.

Now, the interesting thing about bonds is that even though they're a debt instrument, in order to sweeten the pot and attract investors, issuing companies will often add features and wrinkles into the wording of the bond contract. For instance, a bond might be convertible into common shares in the company. Now, if that's at the option of the person who holds the bond — the investor — then that makes that bond more valuable because the bondholder can convert the bond into shares if the company looks like its really growing in value.

If the conversion option is on the company's side, then that makes the bond worth less to the investor, because at any time, the company can come along and say, "Well, we're not going to repay you the face amount of the bond or even any future interest payments, we’re just going to give you these common shares instead." That makes the bond worth less.

There are other features that can affect the value of a bond. Call and put options will allow either the issuer or the bondholder to terminate the bond prematurely. If the issuer has the right to call the bond early, and repay the face amount without making future interest payments, obviously that makes the bond worth less to the bondholder. If the bondholder has the option to put the bond, which means they can demand repayment at any time, obviously that makes the bond more valuable. If the company looks like it is running into financial trouble, for instance, it would be very helpful for the bondholder to be able to get their money back before the issuing company collapses, even though this would mean forgoing any future interest payments.

Preferred Shares

Preferred shares are a financial instrument whereby the company promises to make not interest payments, but dividend payments. Like common shares, they represent a stake in the company, but preferred shares don’t entitle the shareholder to vote at the annual general meeting. Also, the dividend on preferred shares is limited to a certain amount specified in the share agreement, whereas in theory, potential dividends on common shares are only limited by the profitability of the company. Although the dividend on preferred shares is limited, companies do have to pay the promised dividends on preferred shares before they can pay dividends on their common shares. That’s where the word “preferred” comes from.

There are lots and lots of features that can be built into preferred shares, and some of them make the preferred share seem very much like a bond. And in other cases those features might make it seem a little bit more like common shares.

For instance, the company might have the right to cancel the shares and give people their money back. Or, the company might have the right to convert the preferred shares into common shares at its discretion. Or, the investor might have the right to convert their preferred shares into common shares at their discretion. All of these features are going to affect the value of the preferred shares as they trade on the stock market.

Dividends on preferred shares are not like interest on bonds. With a bond, the company has a legal obligation to make the specified interest payments. With a preferred share, the company can decide not to pay dividends because it feels it hasn’t earned enough money. Of course, a company that wishes to get along with its shareholders doesn't want to do this arbitrarily, because it would make the preferred shares go down in value on the stock market. It might even make the company’s common shares go down in value, because of the uncertainty it creates about the company’s financial situation.

Because a company can decide not to pay preferred dividends, there is another feature that can be built into preferred shares. They may be cumulative, meaning that the company has to pay out any back dividends on the preferred shares before it can pay any dividends on common shares.

Preferred shares can have call and put options, just like bonds. That is, they can be redeemable at the discretion of the company. or retractable at the discretion of the shareholder. Obviously, just like bonds, these features will affect the value of the preferred share.

Classifying Hybrid Securities

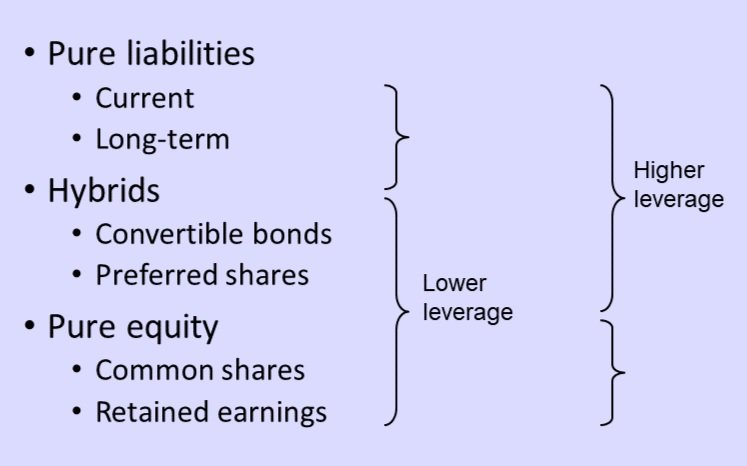

So the question to consider here is, which of these features make bonds seem more like equity, and which features make a preferred share seem more like debt? Features that give the investor the right to participate in excess profits make the security more like equity. Features that guarantee that the investor will receive regular cash payments make the security more like debt.

Hybrid securities can sit in the grey area between debt and equity, but they have to be disclosed in one section or the other on the balance sheet. This gives managers an opportunity to classify them in whatever way is more favorable to the company. This can change the meaning of the value that is disclosed, particularly because it affects the perceived riskiness of the company. If the securities are classified as long term debt, this creates the perception of higher leverage. If they are classified as equity, it makes the company looks like it is less leveraged.

Summary

This has been a rather lengthy discussion of long-term liabilities. Let’s sum up what we’ve learned.

We went over the fundamentals of long term liabilities, including the time value of money and the concept of leverage.

We looked at some basic bookkeeping for debt. We saw that interest has to be accrued as time passes, whether or not it's paid to the creditor. That's the interest expense, which is not the same things at all as interest paid.

We also learned that neither proceeds of a loan nor the repayment of a loan affect the income statement. That all happens on the balance sheet.

We talked about interest-free loans and how to account for the benefit that a company gets from such a loan, and how interest expense will be recorded even if there is no actual interest payment to be made.

Then we talked about the various kinds of debt that have matching assets: a mortgage on a truck or on a factory, short-term leases that are not considered liabilities, and long-term leases that are set up as financial liabilities with matching right-of-use assets, and finally pension plans that involve matching pension assets and pension obligations.

We also went over all those miscellaneous obligations — provisions, contingencies, and commitments — as well as that curious category of disclosures called subsequent events.

Finally, we went over hybrid securities — bonds and preferred shares that may be like liabilities or may be like equity. I did not get into the accounting calculations for bonds because that's beyond the level of this course, but I may add a lesson later on to go over these calculations, just because they are entertaining in a geeky sort of way. The important thing to remember from this lesson is that hybrid securities have to be classified as liabilities or equity, and you need to think about how to interpret them when you are doing leverage calculations.

So, that's it for long-term liabilities. Take a breather and move on to the next lesson when you are ready.

Title photo: skateboarders hanging off the back bumper of a moving ice cream truck. Watch for children.