In this lesson, we're going to take a deep dive into the accounting standards on how to recognize income. The question of when revenues and expenses should appear on the income statement is at the heart of accrual accounting, so you really need to understand this topic well.

A quick note. I'm going to be explaining this topic from the perspective of IFRS 15. That's the international financial reporting standard for how to recognize revenue from contracts with customers.

In the US, where accounting standards are called the "generally accepted accounting principles," or GAAP, the standard with the same name is referred to as Topic 606. There are some technical differences between IFRS 15 and Topic 606, but they aren't big enough to worry about here. They both deal with the core issue of accrual accounting, which is when to recognize revenue and expenses so that the net income for a fiscal period is a more useful indicator of the financial performance of a company.

I'm going to walk you through IFRS because, to me, it offers a clearer conceptual framework for understanding when a company can consider income to be earned. In both cases, in IFRS and in US GAAP, the two key principles of income recognition are the same:

You don't earn revenue until you give the customer the goods or services they've purchased, regardless of when they give you their cash.

You need to match to the revenue, all the expenses that were related to earning that revenue, particularly the cost of making the goods or delivering the service.

So with these core commonalities in mind, let's dive into our topic. Our approach will be straightforward. I'm going to go over the basic steps for recognizing revenue and expenses under accrual accounting, and then I'm going to give you some examples that will help clarify everything.

Revenue and Expense Recognition

The basic issue for revenue and expense recognition is what to do when the process of producing a good or service, delivering it to the customer, and getting paid by the customer, spans a fiscal year-end. If all of this happens during the same fiscal period, you don't really have much of a need for accrual accounting. Cash accounting would be sufficient.

Cash accounting is as simple as it gets. You don't need to computer. Just look at how much money is left at the end of the day, compared to how much was there when you started, and that's your profit.

Unfortunately, for any enterprise more complicated than a lemonade stand, cash accounting doesn't tell you anything particularly useful. It ignores the cost of any previous investments you've made. And it won't account for any inventory you've purchased on credit or any sales that you make on credit. Which means it ignores pretty much all business to business activity until a month later when cash finally changes hands. This produces a very distorted view of the financial performance of a company.

Cash accounting is also very easy for managers to manipulate. Think about this. If you want to inflate your earnings in any given fiscal period, you can just delay paying for your inventory. It may not matter to your supplier if you wait a couple of days extra to pay your invoice. But if that pushes the payment into your next fiscal period, from a cash accounting perspective, you just made this fiscal period look more profitable. Accrual accounting isn't effected by that sort of manipulation.

To be fair, it offers its own opportunities for manipulating earnings, but they're not as simple as just paying your bills on a different day.

Accrual Accounting

So how does accrual accounting work then?

1. Recognize the Revenue

The first step is to figure out when in your relationship with the customer you've actually earned the revenue. Under IFRS, this is all about when you've done the thing that satisfies the implicit contract with the customer. Usually with the sale of goods, it's when you hand them the thing that they bought. With the sale of services, it's when you do the thing they hired you to do. This has nothing to do with when the customer pays you.

In some businesses, like legal practices or construction companies, customers pay a retainer or deposit up front, before the business does any work. That's not revenue for the company until it's earned. In fact, it's explicitly referred to as unearned revenue, which is a liability. Only when the work is performed does the revenue get earned. Debit unearned revenue credit to revenue.

In other businesses, the customer orders some products from you, you deliver the products and then invoice them. They pay you 30 days later. You earn the revenue, but don't get paid right away. So debit to accounts receivable and credit to revenue on the day you deliver the products.

But there's no revenue event when they finally get around to paying you. You already recognized it on your income statement on the day you earned it.

Obviously you need to adopt a consistent policy for this if you want your financial statements to be comparable from one fiscal period to the next. Otherwise you'll end up with sales being included or excluded differently from year to year, just because the timing of revenue recognition is handled inconsistently.

2. Match the Expenses

The second step in accrual accounting is that when you recognize a sale, you also need to recognize any expenses associated with that sale. For goods. It's the cost of the inventory item that you just handed the customer. For services, it's the wages you're paying to your employees to perform the service.

You may have bought the inventory last year, but it sits on your balance sheet as an asset until the day you deliver it to the customer. Only then does the purchase of that inventory item show up as an expense on the income statement: debit to cost of goods sold, which is an expense; credit to inventory, which is an asset.

Everything is driven by the revenue event. You do not recognize the expense first and then match the revenue to the expense. Revenue recognition drives expense recognition.

Now, it's worth noting that the expenses we're talking about here are only the ones that are directly related to the sale of a specific product or service. We call those product costs. But there are lots of other costs in running a business that are not directly related to specific sales events, like the salary of the CEO or the interest on a bank loan. Those are called period costs as opposed to product costs, and I'll discuss those later in this lesson.

IFRS 15

I've just given you an explanation of income recognition in my own words. Now I'm going to go over the same concepts using the more formal language of IFRS 15: Revenue from Contracts with Customers. When IFRS 15 came into effect, it replaced an older accounting standard that made a big distinction between goods and services. The standard setters decided that this was not a useful way of dividing things up, so they came up with IFRS 15 as a clearer way of thinking things through.

By the way, the members of the International Accounting Standards Board, which is the group that decides these things, is made up largely of professional accountants who've come through the Big 4 accounting firms, with a few representatives from the finance industry, big banks and government. I generally have a pretty low opinion of the big accounting firms because they play an instrumental role in global warming and in the incredibly unfair distribution of wealth in the world. However, I think the accountants at the IASB who brought IFRS 15 into existence did an exceptional job of thinking clearly through what is a very complicated topic.

The key to the clarity here is the realization that everything related to revenue can be seen as a contract with the customer. Sometimes the contract is simple, like when someone buys a hammer or a litre of milk. Other times the contract can be complicated with multiple obligations on the part of the seller, all for the same price to the customer.

Under IFRS 15, there are five steps in determining a revenue recognition policy:

Identify contract with customer

Identify separate performance obligations

Determine transaction price

Allocate transaction price to performance obligations

Recognize revenue when (or as) a performance obligation is satisfied

These steps hinge on the two things that I highlighted in bold. The first is the contract with the customer, which might only be implicit. The contract needs to be broken down into separate performance obligations, if there happens to be more than one. For instance, consider the sale of a commercial dishwasher to a restaurant, in which the seller has to deliver the dishwasher to the customer on Tuesday and then provide a 36-month service warranty, involving regular maintenance on the equipment for the life of the warranty. Those are two separate obligations on the part of the seller.

The second is the transaction price. This is often simple, but if there is any complication, such as delays in payments or discounts or trade-ins, you need to sort that all out and determine the price. Once you’ve done that, you allocate it amongst the performance obligations.

I'll show you how to do this later in the course, but for now, imagine that the seller considers the dishwasher to be worth 90% of the price paid by the customer, and the remaining 10% was for the service warranty. This has nothing to do with what the customer's values are. Maybe they didn't care about the service at all, or maybe the service was a determining factor in their purchase decision. Either way, we don't care because we're talking about revenue recognition and that's from the perspective of the seller.

Wait, there’s a warranty?

Take my money!

Once you've allocated the transaction price to the performance obligations, you're then free to recognize revenue as soon as you satisfy each obligation. Delivering the dishwasher is a one-time event, so in our example, we'll recognize 90% of the price when that happens. Delivering the warranty service takes place over a 36-month period, so we would recognize that revenue one month at a time, until the entire 10% of the price that we allocated to the warranty has been earned. I'll go over warranties in more detail later in the course, so if you have any questions about this, hold onto them until we get there.

I now want to go through each of the steps of IFRS 15 in a little bit more detail.

One: The contract

Identifying the contract with the customer is usually quite simple, but IFRS 15 spells out all the key parts to the contract, that must be in place before you can recognize any revenue.

Approval

The contract must be approved by both parties, the seller and the buyer.

With an over-the-counter sale of a litre of milk, this is not an issue. The customer has found, what they were looking for and has brought it to the cash register. By paying for it, they implicitly indicate that they approve the contract. And by allowing them to walk away with the milk after purchasing it, the store has also implicitly approved the contract.

Rights

The contract must make the rights of each party clear. With respect to the product or service. If the customer walks out the door with a litre of milk after paying for it, they own it. But if the customer pays for the milk and asks the store to deliver it to their home, who owns the milk in the meantime? The customer probably has a right to expect that the milk that is delivered will be as fresh as the milk in the store. If it's gone sour, the store will have failed to satisfy their implicit performance obligation.

Payment Terms

The contract must make the payment terms clear. If there's no agreement on when the customer needs to pay for a service, the revenue cannot be recognized. If the contract spells out a series of delayed payments for a product or service that's been delivered, that's fine. The revenue can be recognized as long as the terms are clear.

Substance

The contract must have substance. This means that there must be cash flows in exchange for something of value. You can't recognize revenue if the customer doesn't give you anything substantial in return, and you can't recognize revenue if you've not provided them with something substantial.

If you want to see examples of attempts to inflate revenue figures with exchanges that didn't involve substance, just look at the various attempts of certain football clubs in Europe to get around Financial Fair Play regulations. That topic probably deserves a video of its own.

Collection

Finally, it must be probable that the seller's going to collect the money from the customer. The word probable is a low bar here. You can recognize revenue as long as it's more likely than not that you'll collect. But if you sell something on credit to a customer that's going bankrupt, your auditor is going to politely insist that the sale doesn't count towards revenue. You're not likely to collect from a customer that's going bankrupt.

Two: Performance Obligations

Identifying the performance obligations needs to be looked at partly from the customer's point of view. Did they receive separate benefits or was it all one big benefit?

The example of the dishwasher and the warranty service that I gave before is an example of separate benefits. However, if you're a car dealership and the customer expects not only a new car, but one with that "new car smell." The new car smell is not distinct from the car itself. You can't have one without the other, so they're not separate performance obligations.

Even if the customer pays extra for options to be installed in the car, like a rear view camera or two-way sneeze-through wind vents, they cannot be separated from the new car that is to be delivered by the car dealership to the customer. Those options are not a distinct part of the contract, so while they are a performance obligation, they are not considered separate from the main one of delivering the car.

What about a store that offers loyalty points? Those might be considered a separate benefit to the customer, so the store might need to allocate part of its sales revenue to the loyalty program for accounting purposes. That means that some of the revenue might be recognized when the customer walks out the door with their products, while a portion is not recognized until the loyalty program delivers its separate benefit to the customer.

Again, I've got a lesson on this. We'll get to it later, but if you're interested in it now, go ahead and have a look.

Three: Transaction Price

Determining the transaction price is often easy, but when there are things like coupons and discounts involved, those have to be factored into the calculation of the price.

When something besides cash is offered by the customer, that has to be assigned a value, too, and considered part of the transaction price. Think this sounds unusual? It's not. It's common practice in the car industry, where people trade in used cars to get new ones. The trade-in has to be assigned a value, and that value has to be included in the transaction price.

Imagine if it wasn't. A car dealer could say they'd sold a $50,000 car, when in fact they sold it for $40,000 and a ten-year-old hatchback worth $5,000. That adds up to $45,000, not fifty.

Four: Allocation of Price to Obligations

Allocating the transaction price is actually a complicated calculation. I'll go over it in a separate video, but basically the seller has to figure out a reasonably fair estimation of the value of the different performance obligations. If you normally sell an extended warranty on a TV set for $150, and your salesperson throws in that for free for one of your customers, you have to admit that you just sold the TV for $150 less than the regular price. Part of what the customer is paying for, has to be allocated to the warranty service.

There are lots of other wrinkles that can come into play. What if you offer a discount to the customer if they buy three of something?

What if the price can change because of some future action by the customer, such as paying the invoice quickly, or exercising a right to return part of the purchase? All of these can affect the contract price. As I said, this can get complicated and I've got an upcoming video devoted to this topic for the really keen students to enjoy.

Don't blame the complication here on IFRS though. These complications come up because businesses keep inventing new ways to separate customers from their cash, and IFRS is just trying to keep up.

Five: Satisfaction of Obligations

The last step in recognizing revenue is usually straightforward. You deliver the goods or you deliver the service, and at that point you have a legal right to be paid. If there are complications in the task to be performed, such as a gap between the seller giving up possession and the customer taking possession - in other words, a courier company gets paid to deliver the goods to the customer - then this has to be thought through carefully.

A phrase that frequently pops up in this discussion is "the risks and rewards of ownership." If the customer can now enjoy the benefits of owning the product, such as being able to watch YouTube videos on the new phone, or if they have taken on the risk of the phone being damaged or stolen, it's fair to say that the obligation to deliver the phone to them has been satisfied. If any part of that isn't clear, then the revenue recognition situation isn't clear.

Generally a company will adopt a policy that applies to all similar sales. Sales of cell phones will be recognized when certain conditions are met and this applies to all cell phones, while sales of dishwashers might be recognized differently because there's a delivery service involved.

As long as the accounting policies are applied consistently to all similar sales, it's perfectly fine for dissimilar sales to have different accounting policies.

Exercise: Part 1

Now that we've been through IFRS 15 in some detail, I want you to pick one or more of the examples shown here and think through how you would apply IFRS 15:

Store sells appliance with 30-day return policy, 90-day regular warranty, and three-year extended warranty

Contractor builds an office tower for a client

Dealership sells new car for 10% down, self-finances the balance

Telecom company signs up a customer to a two-year phone contract, paid monthly, includes “free” new phone

University sells an eight-month parking pass, paid in advance

Airline sells ticket that generates travel rewards points

Think about performance obligations and about the transaction price. If you're studying this course along with someone else, discussing the ins and outs of IFRS 15 with them can be a great help.

So pause the video and think.

Matching Expenses

Now, as we mentioned at the beginning of this video, once you have a clear idea of how to recognize revenue for something, you need to think about the expenses that went along with earning that revenue.

Product Costs

Whenever there are costs that can be matched to a specific performance obligation, such as the delivery of the product or the delivery of the warranty service, those costs should be recognized at the same time as the revenue is recognized for that obligation.

This can get a bit tricky when you don't yet know what the cost will be. For instance, when you sell someone a product with a warranty, you have a pretty clear idea of what the product costs you to buy wholesale, or to make, if you're a manufacturer.

But the cost of delivering the warranty won't be known until the end of the warranty, when you no longer have to pay anyone to go out and repair it, or you no longer have to provide a replacement for any broken parts.

This is where estimates come in. Because the likelihood of a product breaking or needing an hour of service is predictable, you can estimate what the costs will be and recognize the expense for those costs at the same time as you recognize the revenue.

And these things are predictable because products in contemporary capitalism are engineered to break on a predictable basis.

If you build something better than it needs to be built for the price being charged to the customer, you're wasting your own money. Companies try to build products to a certain level of reliability, and then charge more for higher quality and less for lower quality. They know from their engineering, what the breakage rate will be on average.

Even if it's a brand new product, they have transferable experience from building similar products before. Or they can look up the breakage rate for similar products made by other companies. It's not rocket science. It's statistics.

Whenever costs are estimated in advance, there will be some discrepancy between the prediction and the reality. That's normal. There are accounting procedures to adjust for this after the fact. All of that is covered in the lesson on warranties.

Period Costs

The last thing to discuss here is the notion of period costs. These are the monthly management salaries and office rent and insurance premiums that are just part of the cost of running a business and are unrelated to any specific sale. They're called period costs because the expense for these costs is simply recognized in the fiscal period in which the cost is incurred.

If you pay monthly rent, you recognize that expense every month, if you pay monthly insurance, you recognize that expense every month. But if you prepay your rent or prepay your insurance, you recognize the expense, not when you pay for it, but when the benefit is received.

Paying six months of rent in advance means a monthly rent expense of 1/6th of the amount you paid. Paying two years of insurance in advance means a monthly insurance expense of 1/24th of the amount you paid.

The same principle applies when you're talking about fixed assets. Those are paid for up front and set up as assets on the balance sheet.

The cost of these assets is recognized as an expense by amortizing the asset or depreciating it on a monthly basis. The schemes and options for this are something I talk about in the video on fixed assets or long-term assets, but the underlying principle is what we're talking about here: period costs that are recognized as time goes by, not as sales happen.

Estimated Expenses

Here are some examples of expenses that depend on future events, but which can be estimated quite well:

Bad debts expense

Returns

Warranty costs

I’ve explained warranty costs above. Bad debts are when you sell to someone on credit and they fail to pay the invoice. Perhaps they went out of business entirely. When you start up a business, you may have to guess at the reliability of your customers, but after running the business for a few years, your ability to estimate bad debts will have improved due to the fundamental accounting principle of "shit happens."

Returns are when customers bring back goods for a refund. That radio shack store that I worked at in Moose Jaw years ago had two kinds of returns: people who brought the equipment back because it didn't work, and people who brought the equipment back because the party that they bought it for is over, and they just took for granted that we give them a refund. You learn a lot about people from watching them return stuff.

At any rate, managers have to use their own experience and as much data as they have to form the estimates they use. Obviously there's a cost to data. So sometimes it's not worth tracking stuff closely. Sometimes a rough estimate is good enough. But we'll learn later how managers can take advantage of the flexibility built into accounting estimates to tinker with their financial results. You'd hope that an auditor would question this, but ultimately, what does an auditor know about the likelihood of people in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan returning a stereo system? The store owner in Moose Jaw is the world's leading expert.

It's easy for business managers to change estimates. It happens all the time and hopefully most of the time it's for very good reasons. Any accounting policy can be changed. You do have to let the readers of your financial statements know about your policy changes though, so that they can decide whether they're willing to trust your numbers.

Any time a company changes in accounting policy. It raises a lot of questions about whether the managers might be trying to game the system, for instance. So companies tend not to change their policies unless they have a good reason.

Exercise: Part 2

Okay, we've gone over the product and period costs and the basic idea of using estimates to allow future costs to be recognized as expenses when revenue is recognized, instead of waiting until the cost is known. I'd like you to take the time now to think about the revenue stream or the streams that you picked from the previous exercise.

What are the expenses related to that revenue and what are the options for recognizing them? If there are alternative possibilities for recognizing the expense, which ones make the most sense to you and why?

Again, it's helpful to have someone to discuss these things with. You might want to consider leaving your thoughts in the comments section below.

Accrual Examples

To wrap up this lesson, let's have a quick look at some accrual accounting examples of revenue and expense recognition. This won't be exhaustive, but it'll be just enough to make the ideas we've discussed a little bit more concrete.

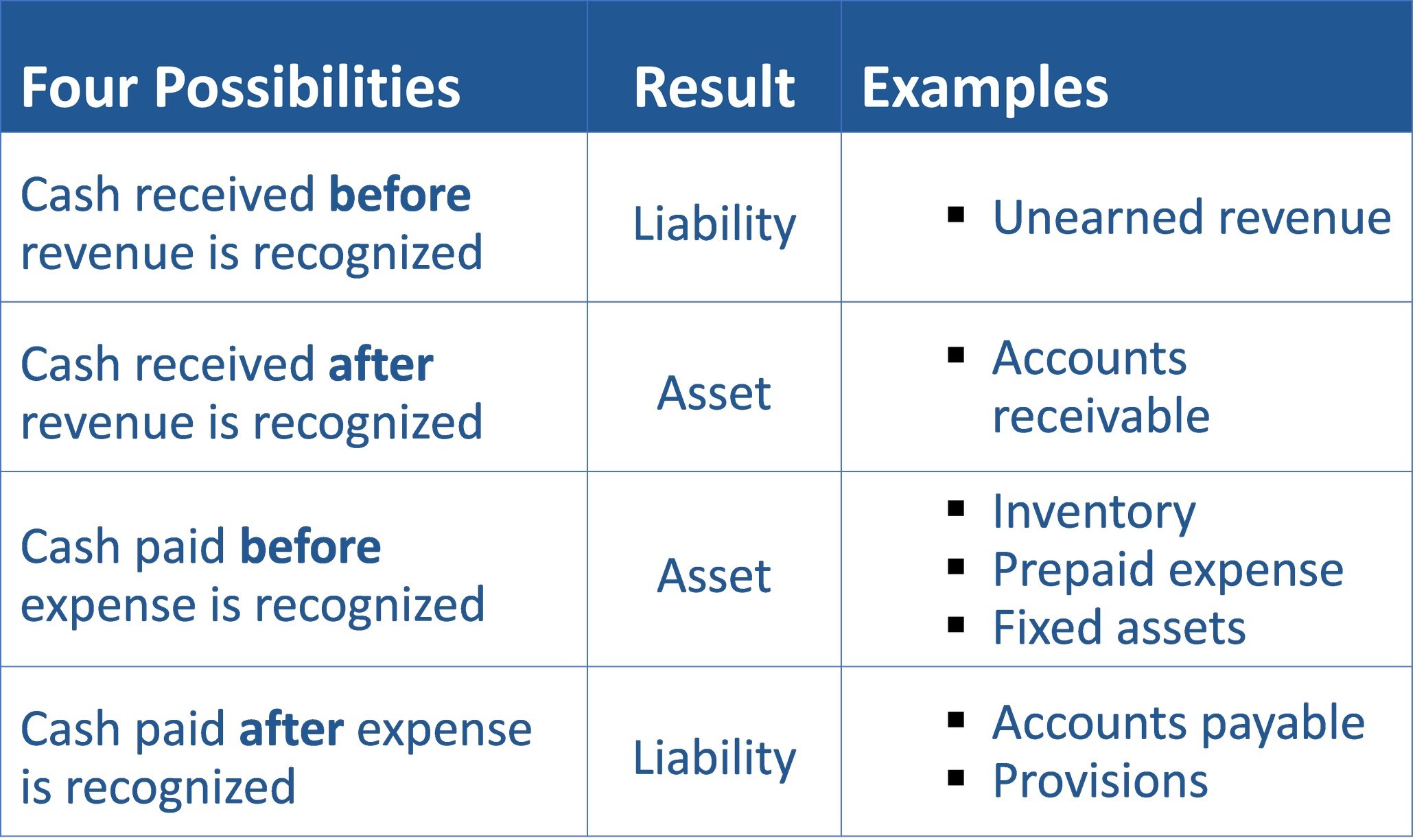

You've seen the table below before, in a different format, when it was a two by two matrix. It shows how differences in timing between recognition and cash flows give rise to either assets or liabilities:

In this version of the table, I've just listed the four possibilities down the left-hand column. This lets us connect them to some examples in the right-hand column.

For revenue recognition, if cash is received before revenue is recognized, you create a liability. The most obvious example might be unearned revenue, also called deferred revenue. You have received money from a customer, but haven't earned it yet. As long as you hang onto the money, you have a performance obligation, hence the liability.

When you get around to satisfying the obligation, you'll debit the liability and credit revenue.

If cash is received after revenue is recognized, you have an asset. The most obvious example here would be accounts receivable. You have delivered a product or service to your customer and have already recognized the revenue for that on your income statement, but you haven't been paid yet. Until the customer pays you, you have a legal right to be paid, hence the asset.

When the customer pays you, you'll debit your cash asset, increasing it, and credit the accounts receivable asset, decreasing that, changing only these two balance sheet accounts.

If cash is paid before an expense is recognized, you have an asset. There are so many possibilities of this:

Inventory, which you purchase as a current asset and which only moves to the income statement, as cost of goods sold, when it's actually sold.

Prepaid expenses, which are not moved from the asset section to the income statement as an expense because there was some kind of a sale, but rather they're amortized over time.

And fixed assets, which are paid for up front and then depreciated over time.

If cash is paid after an expense is recognized, you create a liability. The simplest example is accounts payable where you've incurred an expense, but haven't paid for it yet.

Provisions are another important example. They are when a company estimates a future costs that is likely to face, such as losing a lawsuit or having to clean up a mining site. The company recognizes the expense now and only pays for it later. This is done because the expense is usually related to some previous revenue-generating action by the company, such whatever they did that led to the lawsuit, or operating the mining site. Recognizing the future cost as an expense now fits the matching principle of income recognition because the revenue that the cost is related to has already been recognized. The expense gets recognized with a debit to the appropriate income statement expense account, but the credit doesn't go to cash because you're not paying for it yet. It goes to a provision account in the liability section. That liability will eventually be used up as you pay for whatever the provision is about.

Here's a little more detail on the four possibilities, so you can see the debits and credits in action.

Revenue Recognition

Example 1

The first one is the case where revenue is recognized before getting paid. First, the service is performed and revenue is recognized on the income statement.

Later, payment occurs, but there's no impact on the income statement at that time.

The only account shown here that affects the income statement is the credit to revenue. That's when the income statement is affected.

Example 2

A scenario that we left out of the table on the earlier slide is the one where revenue is recognized at the same time as payment occurs. This doesn't result in any asset or liability. You recognize revenue at the time you're paid the cash. This updates the income statement immediately.

I'm only including this to make it clear that accrual accounting is perfectly capable of handling sales that don't require accruals. This may seem obvious, but I wanted to make sure it was clear.

Example 3

When revenue is recognized after getting paid, you have a liability. The payment happens first with a debit to cash and a credit, not to revenue because you haven't earned it yet, but to a liability account, unearned revenue. Later, when the service is performed, the unearned revenue is debited and revenue is credited, resulting in an increase in income on the income statement.

Expense Recognition

Those examples were all about income recognition. On the expense recognition side, let's look first at the example of rent.

Example 1

Rent is a period cost, not a product cost, so you don't have to match it to any revenue event. It's just recognized during the time that you received the benefit of the expense, in this case, the use of the premises that you're renting.

If rental payments are made every month, there is no accrual. There's simply a debit to rent expense and a credit to cash because you've paid money to the landlord. It's the rent expense here that affects the income statement.

With prepaid rent, however, you need accrual accounting to sort things out. Suppose that instead of paying the rent monthly, you pay the rent six months in advance. This is a credit to cash, of course, but the debit does not go to the income statement. It goes to prepaid expenses, which is a current asset.

Then when each month passes, you amortize the prepaid expense by one month with a debit to rent expense, and a credit to prepaid expenses.

In both cases, it's the rent expense that affects the income statement. It happens once a month when you're paying monthly. And it also happens once a month when you pay in advance and then amortize that prepaid expense over the life of the rental agreement.

Example 2

Here is a second example of expense recognition, this one involving inventory. This is a product cost, so you recognize the expense at the time of a sale.

The inventory is purchased first, and in this case, we'll assume that you paid cash. It's entirely possible that you were invoiced and paid for it later. In either case the recognition of the expense is completely disconnected from any exchange of cash.

When the goods are sold, you get to recognize the revenue with a credit to revenue and a debit to either cash or accounts receivable. Let's assume that you sold the goods on account. So the debit is to AR. At the same time as you recognize the revenue, you also recognize an expense for the product costs associated with it.

This expense is recognized as cost of goods sold. Which involves at credit to inventory, decreasing your assets and a debit to the cost of goods, sold account, increasing your expenses. The revenue and the expense are recognized at the same time.

Later when your customer eventually gets around to paying you, you convert your accounts receivable asset into a cash asset, debit to cash credit to AR.

Now look carefully at these transactions. There was no impact on the income statement when you bought the inventory and none when the customer paid you. The income statement was affected only when you sold the inventory.

In this example, the sale generated a gross margin of $3,000 because, happily, you sold the inventory for more than it cost you. Congratulations!

Example 3

The final example is the most complicated one. It's the purchase and depreciation of a truck. We've got an entire lesson on depreciation, so don't worry if this feels like a bit of a stretch. Looking at it briefly now will help seed the concepts in the fertile ground of your brain, and then when we come back to it, you'll be in an even better position to comprehend everything.

This is another example of a period cost, so the expense recognition is not tied to any revenue event. Let's work through this together.

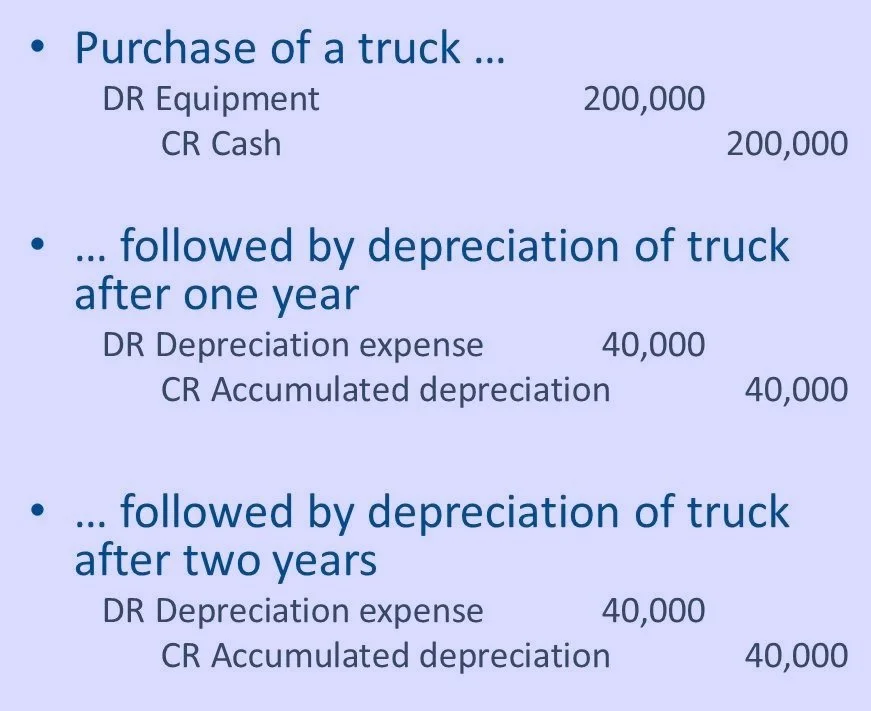

It all starts with the purchase of a truck.

Here we're paying $200,000 cash for it, so that's just moving value from one asset class to another. No effect on the income statement yet.

Tangible assets like trucks are always depreciated on some sort of a regular basis because they wear out. Here we decide to amortize 1/5th of the cost every year, so one year after buying the truck, we depreciate it by $40,000. That means recognizing $40,000 of expense with a debit to the depreciation expense account.

The credit could go to the equipment asset account to reduce the value of that account directly, but accountants have found a more useful way of keeping track of these credits. They create what's called a contra account. In other words, an account that stored alongside another account, but with the opposite normal balance. The equipment account normally has a debit balance because it's an asset. The contra account here will therefore normally have a credit balance. We call it accumulated depreciation.

If we ever want to know the book value of the equipment that we own, we have to remember to add together the asset account and its contra account, accumulated depreciation.

Now when we bought the truck, its book value was $200,000 because there was nothing in the contra account yet.

After the first year has passed and the depreciation has been expensed, the book value will be $160,000, the net between the historical cost of $200,000, a debit, and the accumulated depreciation of $40,000, a credit.

On the balance sheet, usually only the book value would be displayed. The details on historical cost and accumulated depreciation would be in the notes to the financial statement, where interested readers would go to look more closely at the asset values.

After the financial statements for the year have been printed, the depreciation expense account will be closed to retained earnings because it's a temporary account. The accumulated depreciation account, however, will still have a credit balance of $40,000 because it's a permanent account, just like the equipment asset account.

After the second year of owning the truck, we depreciate it by another 1/5th of the historical cost.

Keeping the depreciation amount constant is the simplest method of depreciation, which is why so many companies depreciate their assets this way. Doing this moves another $40,000 of expense to the income statement. But remember, this is the next year's income statement.

It also adds another $40,000 credit to the accumulated depreciation account. This is a permanent account, so the balance in that account is now a credit of $80,000. This means that the book value will now be $200,000 minus $80,000 = $120,000.

We would usually plan to continue this pattern of depreciation expense every year, until we reach some point that we decided on an advance, some residual value where we'd stop depreciating the asset and just leave it sitting on the books as an old truck. In this case, however, we change our plans and decide to sell the truck after two years.

What happens next will depend on the price that we get for reselling the truck.

Whatever the price is, the total expense for the truck over the time that we owned it will be the original purchase price minus the amount that we got for reselling it.

Now it's highly unlikely that we will get exactly book value for the truck when we resell it. Right now the book value is $120,000. And while it would be nice and clean to sell it for that amount, probably we'll get a bit more or a bit less for it, depending on the condition of the truck and the state of the used truck market in our city.

Let's assume that we can only sell it for $100,000, which is less than book value. This is what the transaction would look like.

Here we record the $100,000 that we get from the buyer. That's a debit to cash. Then we have to clear out the historical cost of the truck from the equipment asset account, and also clear out the accumulated depreciation from the contra account. That means putting a credit in the asset account for $200,000 and a debit in the contra account for 80,000. If you net these out, you'll see that the transaction's out of balance by $20,000. So we add a debit to the transaction for that amount.

That amount, that difference between the book value and the price we got for the truck needs to go to the income statement. In this case, it's a debit, so that's disclosed as an expense called "loss on disposal of assets." Typically this expense is disclosed after the operating income's been calculated on the income statement, to show that this transaction is not part of our usual operations.

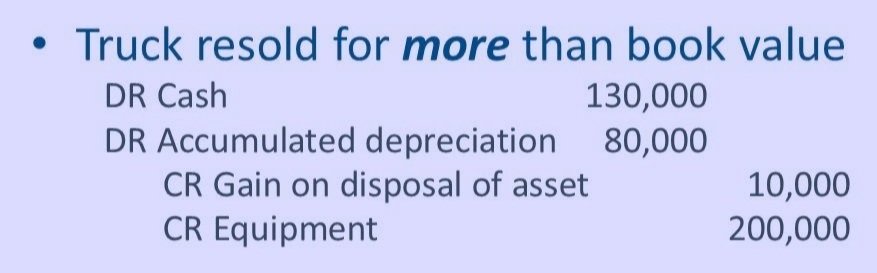

Now imagine that instead of selling the truck for 100,000, we got 130,000 for it, which is more than its book value. Here's what that transaction would look like.

Here, the debit to cash is larger because we got more for the truck.

The debit to the contra account and the credit to the asset account are identical to the first scenario because those amounts were determined long before we sold the truck. Getting more for the truck now does not change how much it cost us when we bought it or how much we've depreciated it since.

The difference between the selling price and the two book value accounts is now $10,000 in the other direction, so we need to credit to balance this version of the resale transaction.

That amount, that difference between the book value and the price that we got for the truck, needs to go to the income statement, just like the first scenario. In this case, however, it's a credit, so that's disclosed as a kind of revenue called "gain on disposal of assets."

We don't add this revenue to our main sales revenue, because that would muddy the waters for anyone trying to assess our financial performance. Just like the loss in the first version of this resale, a gain is disclosed lower down on the income statement after the operating equipped.

After the operating income has been calculated.

So here we can see that the impact on the income statement over the life of the truck is equal to the original purchase price, less the resell price that we got for it.

In the first case, we have a $40,000 depreciation expense at the end of year one, and another $40,000 depreciation expense at the end of year two, plus a loss of $20,000 when we sold it.

That's a total of $100,000 of debits, all of which went to the income statement, albeit in different years.

This total is exactly the $200,000 purchase price, less the $100,000 resale price.

In the second scenario, the depreciation expenses are offset by a small gain on the disposal of the truck, rather than a loss. The total expense here is therefore $40,000 plus $40,000, less $10,000, for a net of $70,000 worth of expense that went to the income statement.

That's exactly the $200,000 purchase price less the $130,000 resale price that we got in this scenario.

Summary

That was a lot of detail, so don't worry if it was a bit overwhelming, consider reviewing the parts of this lesson that confused you and maybe coming back to it again later to let it really sink in.

Let's summarize what we've covered.

This lesson, despite all the debits and credits that we just went through, was not primarily about bookkeeping. It was about when a company should recognize revenue and when it should recognize expenses.

Revenue recognition is the primary issue. To recognize revenue, you have to examine and parse the contract with the customer. Sometimes that contract is explicit. Other times it's just implicit in the usual way sales transactions take place in our economic system.

In examining the contract with the customer, what we're looking for is distinct performance obligations, so that we can allocate the transaction price to these obligations and recognize the right amount of revenue whenever we satisfy another performance obligation.

There will often be timing differences between when cash is exchanged and revenue is recognized. That's the whole point of accrual accounting.

We also made a distinction between product costs and period costs.

Product costs are recognized as expenses at the same time revenue is recognized. The best example of this is cost of goods sold, which is the cost of the inventory that you give to the customer.

Period costs are recognized as expenses as time goes by. They're not triggered by any specific revenue event. Examples include rent and depreciation.

We then went over a number of accrual examples, showing which parts of the various revenue and expense transactions impacted the income statement.

I hope you found them helpful. As I said, don't worry if they were a bit overwhelming to you. We're going to be going over lots more examples in this course, and I encourage you to practice them on your own, too.

Whenever you are ready, move on to the next lesson.

Photos: With a handful of exceptions, every photo on this website was taken by me, Cameron Graham. The photos on this page are exceptions. I got them from Unsplash because it turns out I have take surprisingly few photos of income recognition. I picked the title photo because I find it so evocative for the theme of income recognition. The others just appealed to me.