In this lesson, I want to go over some of the technicalities around revenue recognition. Revenue recognition is a quintessential accrual accounting topic. Yes, it's a bit advanced, but I like putting it into an introductory lecture because I think it's important to undermine the notion that sales are simple. There's actually lot of future events that could take place — returns, warranty claims, and so on — that you have to make allowances for when you sell something. So, let's see what we can learn.

I want to go over three different things that you need to be able to handle when recognizing revenue under accrual accounting:

Discounts for early payment

Returns

Warranties

In all of this, I’m going to be relying on IFRS 15, the International Financial Reporting Standard covering contracts with customers.

First up, discounts for early payment.

Discounts

Direct Method

The simplest way to account for discounts for early payment is the direct method. And a lot of companies use this. So consider a scenario where something is sold on "2/10 n30" terms. This means that the customer has been offered a 2% discount if they pay within 10 days, otherwise they have to pay the total amount of the invoice within 30 days.

Under the direct method, you would simply record the sale in the normal fashion, debit to accounts receivable, credit to revenue. And then you just wait to see if you collect from the customer within 10 days. If you do, on a $1,000 purchase you’ll receive $980 from the customer. You’ll debit cash for $980 and you’ll clear out the accounts receivable of $1,000. That leaves you $20 left over.

That gets debited to a sales discounts account. That is what is called a “contra revenue” account. Contra accounts are behind the scenes, so to speak. Several amounts displayed on the financial statements involve contra accounts. If you look closely at the top line on the income statement of most organizations, it doesn’t just say “Sales” or “Revenue.” It says “Sales, net” or “Revenue, net.” What this means is that the amount displayed is the gross revenue minus any discounts or returns. It’s not just all the sales, but rather, all the sales that counted.

So in this case, the revenue account would hold $1,000 and the sales discount account would hold $20, and on the income statement, those would be combined together into a net sales line that says $980. That matches the cash that was received, so everything is in balance. Now the problem is, what happens if the sale is near the end of the month? Because then you're going to have the possibility of the sale occurring in one month and the discount occurring in the next month.

If that happens and you don’t do anything about it, your income for the first month would include the $1,000 and the income for the second month would already start off in the hole by $20. The revenue would be overstated in the first month, because you didn't really earn $1,000, and it would be understated the second month because the $20 discount isn’t related to any sales in that month.

So what's the solution? What you want to do is, at the end of the first month, estimate the discount that the customers will take and adjust for this by setting up an allowance. Let's see how to do that.

Allowance Method

Imagine a scenario where, during the last 10 days of the year, a company sold $2 million worth of goods, sold on the 2/10 n30 terms that we discussed above: so, a 2% discount for early payment within 10 days, otherwise the balance is due in 30 days.

And, here's the crucial thing: the company needs to understand what its experience is with all its customers. Let’s assume that this company has discovered, by looking back at previous data, that 60% of its customers pay within 10 days in order to take advantage of the discount.

The other thing to think about is that we actually need two allowance accounts: one that is contra to revenue, and one that is contra to accounts receivable. When we sell to customers on account, we recognize revenue and we simultaneously set up the amount they owe us in accounts receivable. If a customer takes a discount, that is going to affect both of these numbers because we won’t get the entire amount of the sale as revenue, and we won’t collect the entire amount of the accounts receivable.

Our priority, when using the allowance method for sales discounts, is to get the balance sheet right. That means we want to do an accurate job of estimating the allowance in relation to accounts receivable, so that the net amount we show is a fair representation of what we expect to collect. The allowance for the sales discount that is contra to revenue is not as important. (Accountants always have to pick their priority, because you can’t do a good job of estimating both the balance sheet and the income statement allowances accurately. In this case, the priority is the balance sheet.)

Because balance sheet accounts are permanent, the allowance account that is contra to accounts receivable may well have a balance left over in it from the previous year. That means we will have to adjust it to end up with the balance we want. In this situation, we're going to assume the allowance account already has $10,000 debit balance sitting in it.

So let's think about what that is. We're going to be adjusting an allowance that is contra to our accounts receivable. Accounts receivable normally has a debit balance. So,, the contra account would normally have a credit balance. But in this case, it has a debit balance as a result of previous discount transactions. (All this means is that, when the company estimated its, allowance last year, they underestimated and ended up with customers taking more of a discount then was anticipated.) We need to wipe out that debit balance and then credit the account for the additional amount we need to end up with the allowance we are after.

Now, in the last 10 days of the year, we had $2 million worth of sales. What should we show on the balance sheet for an allowance for possible discounts?

Well, the company had $2 million worth of sales in the last 10 days of the year, which is the period open to discounts. We can, therefore, calculate the amount the company is unlikely to collect from its customers. We've got $2 million worth of sales, and a 2% discount offered to customers. That would give us a $40,000 allowance. However, we're only expecting 60% of that to be claimed, based on past experience. This means that we want the allowance to have a $24,000 credit balance, in order to handle the discount that we're anticipating customers will take.

The problem is, there's already a $10,000 debit balance in that account. If we want it to read $24,000 — and we do — what we need to do is not put in a $24,000 credit, but a $34,000 credit. This way, the $10,000 debit balance will be wiped out and the remaining balance will be $24,000 credit.

Here is the calculation and the resulting adjusting entry:

Let’s just clarify what we’re doing. We're focusing on the allowance for sales discounts, which is a contra AR account. Under IFRS, there's a bit of a bias towards getting balance sheet accounts as accurate as possible, using our best efforts to estimate things correctly there rather than on the income statement. Part of the assumption that it’s more important to get the value of assets and liabilities right than it is to measure a company’s financial performance. The other part of the assumption is that by focusing on the balance sheet values, any discrepancies that arise as a result of the process will end up on the income statement, where the numbers are often very large compared to the balance sheet numbers. That makes the effect of any discrepancies there relatively minor. When you look at accounts receivable, for instance, that's usually a small amount compared to a company’s revenue for the year.

The result of our calculation here is that we're going to have a relatively accurate $24,000 estimate for the allowance for sales discounts (the $34,000 adjustment less the $10,000 debit that was in the account when we started), which is a contra account to accounts receivable. This means that the value we show on the balance sheet for A/R is $24,000 lower than the gross value of A/R, all because we are predicting that 60% of our customers will take the discount we offered them for early payment.

The sales discounts account itself, which is on the income statement as a contra revenue account, will be $34,000. That will reduce the amount of revenue shown on the income statement, but because revenue is usually a much larger number than A/R, any slight inaccuracy in estimating sales discounts (as opposed to the allowance for sales discounts) will be trivial compared to the millions and millions of dollars of sales this year. Remember, this is a company that sold $2 million just in the last 10 days, so that $34,000 contra revenue account is quite small in comparison.

Now that we’ve set up the allowance for the anticipated discounts, as a contra account to A/R, what will happen when customers actually do make a payment?

Let’s think about how you would record a collection from a customer under two different scenarios, one where the customer pays for a $1,000 sales within the 10 day period and one where the customer pays for it later, say in 30 days.

So the first scenario, where we collect from the customer within the 10 day period, means that the customer has taken advantage of the 2% discount we offered for early payment. On a $1,000 sale, 2% is $20. So we only collect $980, because that's all the customer would send us. They took the $20 discount. Together, the $980 payment and the $20 discount take care of their entire $1,000 obligation to us for the sale. We're therefore going to credit accounts receivable for $1,000, and debit cash for $980, since that’s the amount we received. And what do we do with that $20 that is left over? We need to record that to balance things out. So, we're going to use up some of the allowance for sales discounts, which had a credit balance at $24,000.

We use up a little bit of the allowance for this customer. The $1,000 sale that we're collecting on, is just a small part of the $2 million that we're hoping to collect, so we're just using up $20 of the $24,000 allowance.

Now, what about a customers that didn't pay within the 10 day period, from the 40% of customers that we anticipated would not take the discount? They are going to be handled with a straightforward debit to cash for the $1,000, because they have to pay the full amount, and a credit to accounts receivable for the same amount.

What we're hoping is that, in the grand scheme of things, approximately 60% of the customers will claim that discount and use up the $24,000. The rest will pay full price. Because estimates are never perfect, we're probably going to have a little bit of the allowance left over, either a slight debit or a slight credit balance. That will just sit there until the next time we estimate the allowance, which may not be until the end of the next fiscal year, when we'll repeat the process all over again. This year we had $10,000 debit balance left over. Next year it might be a $2,000 credit balance, if we didn't use up the entire $24,000 allowance that we just created. Time will tell.

Returns

All right, let's look at returns. Just as with sales discounts, there is a direct method for handling returns.

Direct Method

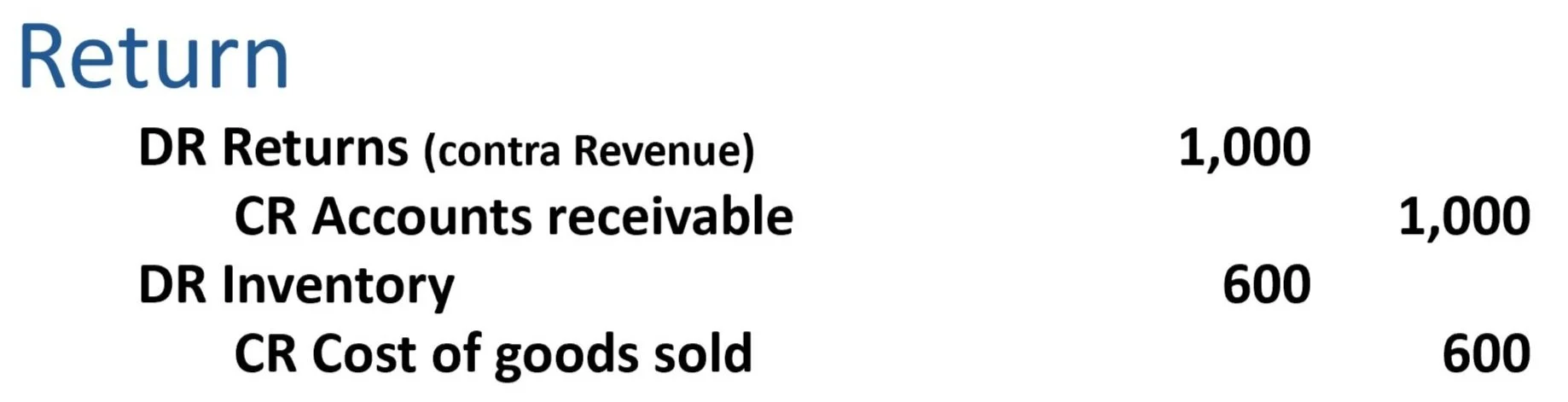

First, let’s record the sale itself, so that our customer has something to return. Let’s say it’s a sale on account, meaning a debit to accounts receivable and a credit to revenue. This recognizes the revenue, so according to the matching principle of accrual accounting, we’ve also got to recognize the expense. We therefore have a debit to cost of goods sold for that expense, and a credit to inventory, because the goods that we sold came out of our inventory:

As a result of all this, the income statement is going to show revenue of $1,000 and cost of goods sold of $600, giving us a gross margin of $400.

What happens, then, if a customer returns the goods and gets their money back?

If we use the direct method, accounting for the return is pretty straightforward. You simply undo everything. The transactions are shown here.

The only difference between this and the sale, other than the debits and credits being reversed, is that instead of debiting your revenue account, you debit “Returns.” This is a contra revenue account.

Using a contra account allows you to keep track of the net sales using two separate accounts, one for the gross revenue and one for the returns. Netting these two accounts gives you the sales that counted, while having separate accounts for revenue and returns let’s you see if you have a problem with excessive returns. If you had debited revenue directly, the net amount would be correct but information would be lost.

The direct method is fine, except if this sale occurs near the end of the year. What if the customer doesn't return the goods until the next year? You'd have a problem because your revenue in the one year would be overstated and your revenue in the next year would be understated. And of course your inventory would be all out of whack, as well.

What should you do to avoid this problem? That’s what the allowance method is for.

Allowance Method

Just as we previously did for discounts under the allowance method, you use an estimate, this time for the likely returns. You use that estimate to set up an allowance for returns and then use the allowance as needed. We’re going to do things a little differently here, though, because instead of setting up one allowance at the end of the year for the sake of your financial statements, as we did above, I’m going to show you how to set up allowances as you go along, sale by sale.

Here's the scenario. Let’s imagine we sold 200 desk chairs in a business-to-business transaction. We’re a manufacturer or wholesaler, and the customer is a retail store. The price of the chairs was $120 each, and our cost on each chair was $90. We're anticipating that 3% of the units that we sell will be returned, on average, by our customers. This is based on our previous experience. So in this case, we anticipate six of the 200 chairs being returned.

Our return policy is that customers can get a full refund if they return any unsold goods within three months. But after three months, the chairs are theirs. We're not taking them back.

How would you record this sale?

You have to set up allowances for all of the stuff that's going to happen. The terms of the sale give the customer a right to return any unsold chairs within three months. At the same time, the seller (that’s us) is given a matching right to recover the unsold chairs.

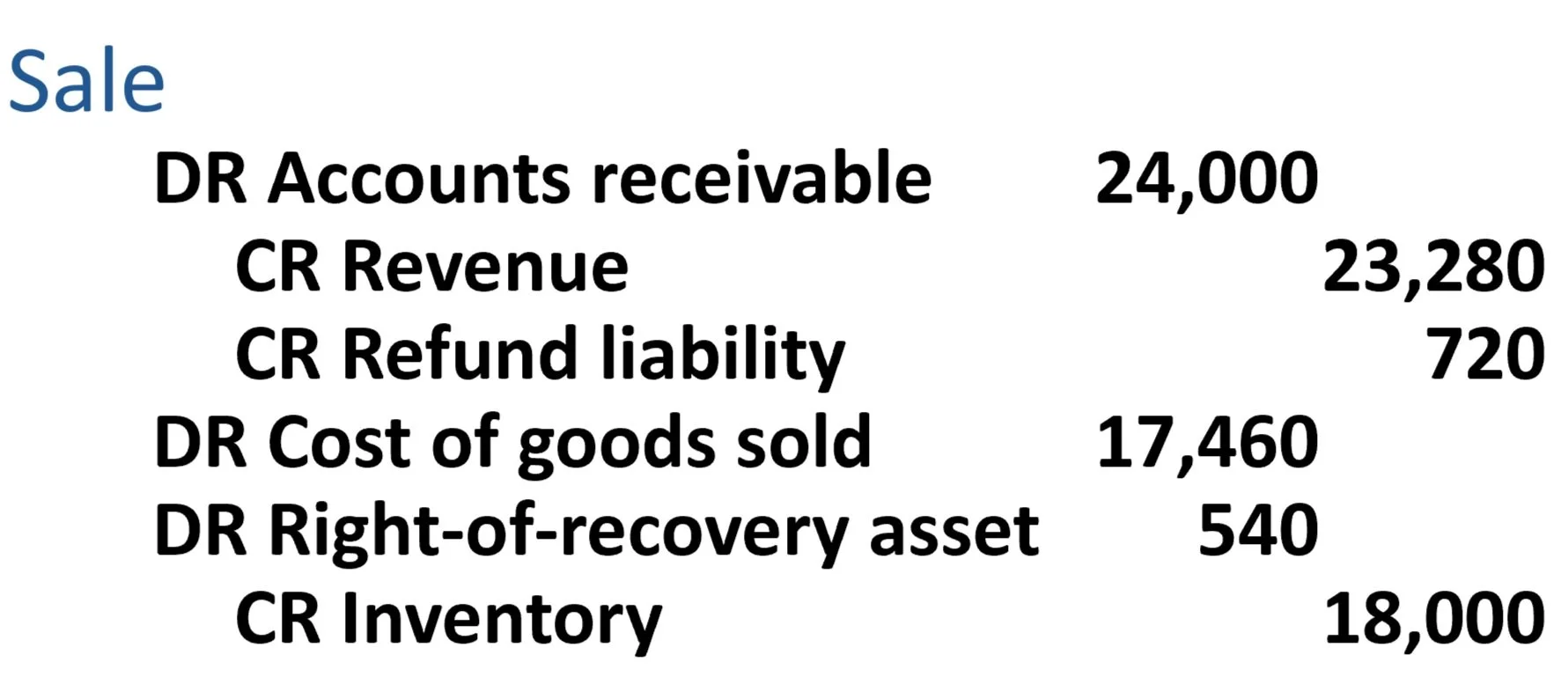

Using the 3% expectation of returns, we estimate six of the 200 chairs will be returned. Calculating the estimated value of the returns, at the selling price, we have six times $120, or $720. Similarly, at cost, we’d have an estimate of six times $90, or $540.

Here’s how we would use these figures to record the sale:

This is probably a bit more complicated than you expected. It's complicated because we want to keep track of everything, including the customer’s right to return the unsold goods and our right to recover them.

The gross amount of the transaction is $24,000. So that's a debit to accounts receivable for the whole amount that we expect the customer to pay, assuming they don't return anything. We're only going to recognize revenue, however, on the goods we estimate won’t be returned, which is the sale amount less the estimated refund of $720. That gives us revenue of $23,280. Conceptually, the $720 is like unearned revenue: we're just postponing the recognition of that amount of revenue until we see what happens with the returns. Like unearned revenue, this will show as a liability on the balance sheet. It's a credit that is not going to show up on the income statement until we are sure we’ve earned it, and if we end up not earning it because of returns, it will just be undone without ever getting to the income statement.

Matching all this, we have a credit to inventory of $18,000, which is the cost of all those chairs: 200 desk chairs at $90. However, just like the revenue part of the transaction, we're going to record as a cost of goods sold only the amount that we expect to stay with the customer. The rest of the debit goes onto the balance sheet as a right of recovery asset.

So, we've set up a liability for the refunds we might have to give and a right of recovery asset for the chairs that we expect to get back. The liability and the asset are not the same value because the liability is based on the selling price of a chair, while the asset is based on our cost for the chair.

Using the Allowance

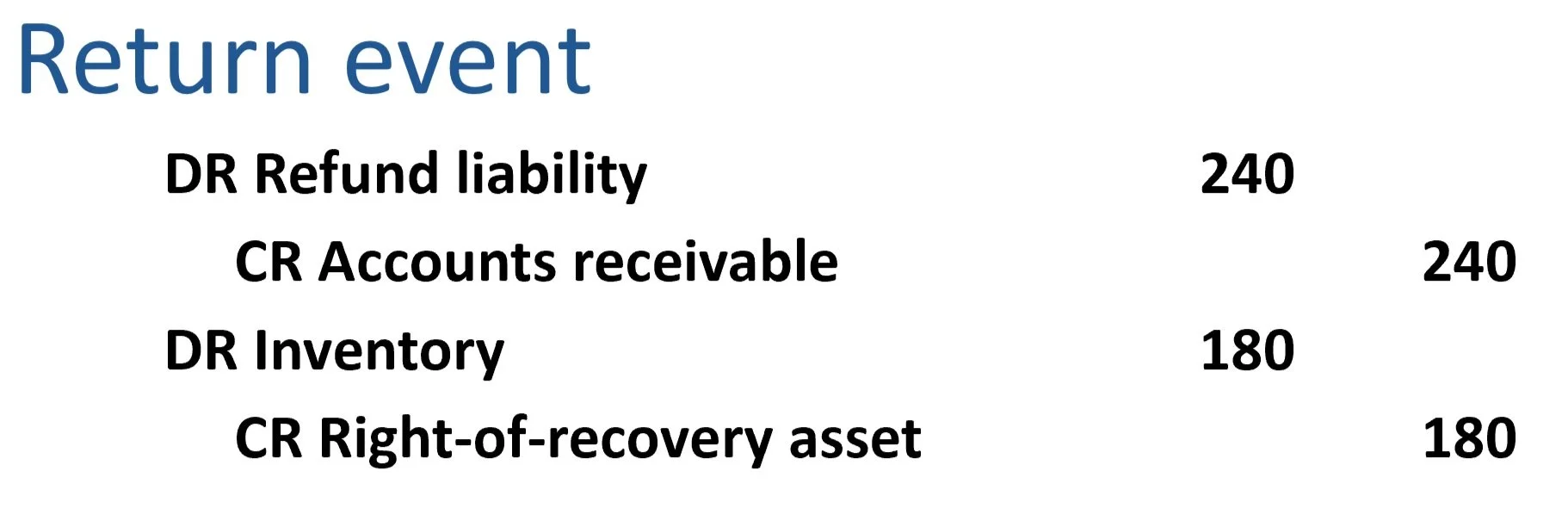

Let's assume that the customer returns two chairs within the return period. We'd anticipated that they would return six, but they only returned two. The effect on net sales is two times the selling price, or $240. The effect on the cost of sales is two times the $90 wholesale cost, or $180. So what do we do with that information? We need to use up the allowances that we set up in the previous slide.

Here's what would happen:

When the customer returns the two chairs, we debit the refund liability for $240 and credit accounts receivable for $240. The gross amount we had set up in accounts receivable for the 200 chairs was $24,000; we reduce that now by $240 because the customer doesn't owe us for these two chairs. The debit goes against the refund liability that we previously set up, because we no longer have an obligation to refund that part of the sale.

On the inventory side, we're going to put the chairs back into inventory. So it's a debit to inventory of $180 (two chairs at $90), while the credit goes to wipe out $180 of the right-of-recovery asset that we set up.

You can easily imagine how the income statement and the balance sheet look after this. Basically, this return event doesn't affect the income statement at all because the accounts we just updated — refund liability, accounts receivable, inventory, and the right of recovery asset — are all on the balance sheet. The changes to A/R and the refund liability reduce current assets and current liabilities slightly, by $240, while the changes to inventory and the right of recovery asset offset each other.

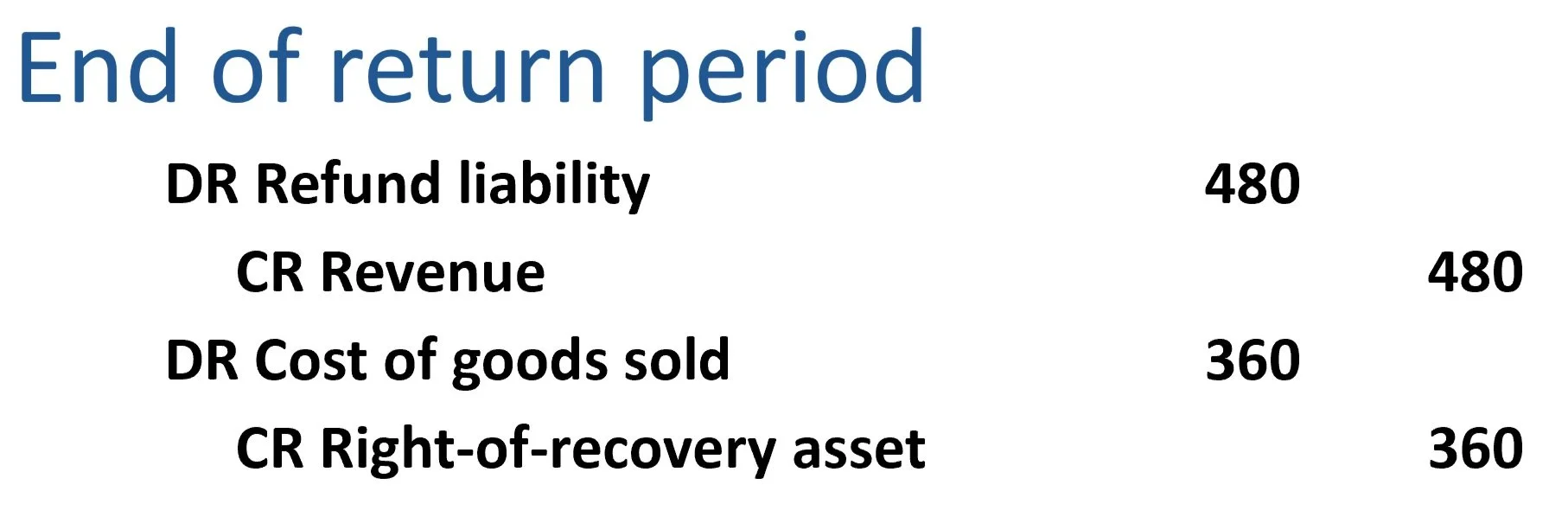

Now, what happens when the return period expires? The customer did not return all six chairs as expected. Four chairs remain unreturned, and will not be returned now because the right to return them has expired. That means there's some allowance left over. There’s also some of our right-of-return asset left over. What are we going to do with these?

We’re going to clear them out:

So, first the refund liability. We still have $480 in that account that didn't get used. Since the customer kept the chairs, that now gets to be counted as revenue. As I said, conceptually this was like unearned revenue, and now we've earned it because the customer has kept the chairs. We're therefore going to cancel the remaining refund liability of $480 and pull it into revenue on the income statement.

Same thing happens with the remaining right-of-recovery asset. We're going to credit it to eliminate the $360 balance that's in there, and then move it over to cost of goods sold.

Basically, if we had done a perfect job of estimating the returns, these balances would be zero, and there'd be nothing to transfer to the income statement. But because we were slightly off in our estimates, we end up with a bit left over this time, which we are now adding $480 to revenue and $360 to cost of goods sold. This increases gross margin by $120.

Assuming we originally sold all these chairs near the end of one year, this adjustment could be happening somewhere into the next year. That means we would have a slight misstatement here. We're going to have a little bit of revenue and a little bit of cost of goods sold being added to this year's income statement, even though it was related to a sale that happened last year. However, we’re still better off than if we had used the direct method, because in that case, we would always be out by the entire amount of any refund that straddled the year-end like this.

At any rate, if we've done a reasonably good job of estimating returns for all our sales, the amount we close out if the right-of-return period expires in the following year will be a relatively tiny amount. With multiple customers, some of them might have returned a little bit less than expected, as was the case here, while others might return more than expected. Those will balance each other out somewhat. The effect on the income statement, the distortion if the sale and the return straddle the year-end, should be minimal.

Warranties

The final sales-related allowance that we want to look at arises in connection with warranties. Warranties are a guarantee by the seller that the goods purchased by the customer — say, a piece of expensive equipment — will perform as advertised for a specified period of time. From an accounting perspective, there are two kinds of warranties, depending on whether the warranty is a separate performance obligation, distinct from simply providing the equipment to the customer. Both kinds of warranty involve current liabilities.

ASSURANCE WARRANTY

The first is the assurance warranty. This is the kind that's included in the purchase price and does not require the seller to do anything but be ready and willing to fix the equipment if it fails during the warranty period. There is no promise to provide any regular maintenance on the equipment. If you buy an electric toothbrush and it comes with a 90 day warranty, you can get it repaired or replaced for free if it stops working during those 90 days. If it works perfectly during this time period, the company you bought it from has nothing to do.

With this kind of warranty, there is only one performance obligation for the seller: to supply a product that lasts as long as the warranty period.

The seller therefore needs to estimate the expense for the warranty service and recognize it at time of sale — the matching principle, once again. The estimate would be based on factors like whether the equipment has been engineered to be durable or cheap, and the seller’s experience in providing the warranty to previous customers.

The resulting warranty expense is a debit, of course, so the credit side of the transaction needs to go somewhere. It goes to the current liabilities as a provision for the future cost of the warranty service. That’s the current liability.

If warranty costs are incurred over the life of the warranty, the provision is debited to reduce it, along with a credit to cash, for example, to pay the service technician, or perhaps to inventory if the repair used some parts or the faulty dishwasher had to be replaced.

If the seller has done a good job of estimating warranty costs, there will only be a small difference at the end of the warranty period. In the example shown, the warranty costs were estimated at $1,000 but only came in at $950. This left $50 in the provision, which can be reversed as it is no longer needed, reducing the warranty expense. (You could, in theory, just credit the warranty expense account, but in practice, it is better to use a contra expense account as I’ve done here, “recovery of warranty expense.” This will allow you to identify these adjustments separately and use them to evaluate your warranty estimation process.) Of course, if the estimate was too small, an adjustment would be needed in the other direction to eliminate the debit balance in the provision and recognize a bit more warranty expense.

SERVICE WARRANTY

The other kind of warranty is the service warranty. It’s often called an “extended warranty” in advertisements designed to entice you into spending more for an appliance or a consumer electronics device. You know the sort of thing I’m talking about. You buy an electric toothbrush that comes with a 90-day warranty, and the sales clerk will inevitably try to talk you into buying a two-year extended warranty for, say, an additional $15. You pay a separate fee for this extra protection, and therefore it's a separate performance obligation for the store, should you give in and buy it. (Don’t give in! Extended warranties are pure profit for retailers. If you don’t believe me, talk to my colleague Moshe Milevsky.)

A warranty also is classified as a service warranty if the terms of the warranty require the seller to perform regular maintenance on the equipment after the sale; you see this more often with commercial or industrial equipment, as opposed to consumer devices. This is regardless of whether or not the customer pays extra for the warranty. If it involves the seller doing regular inspections or oil changes or whatever else is needed to keep the equipment working properly, then that is a separate performance obligation on the part of the seller. The revenue recognition goes like this:

If the service warranty is priced separately, then the accounting is fairly easy, The price of the equipment is recognized as revenue right away and the price of the warranty is recorded as unearned revenue.

If the service warranty is not priced separately, then part of the selling price of the equipment needs to be allocated to the warranty as unearned revenue.

In both cases, the unearned warranty revenue is only earned as the service is performed, month by month over the life of the warranty.

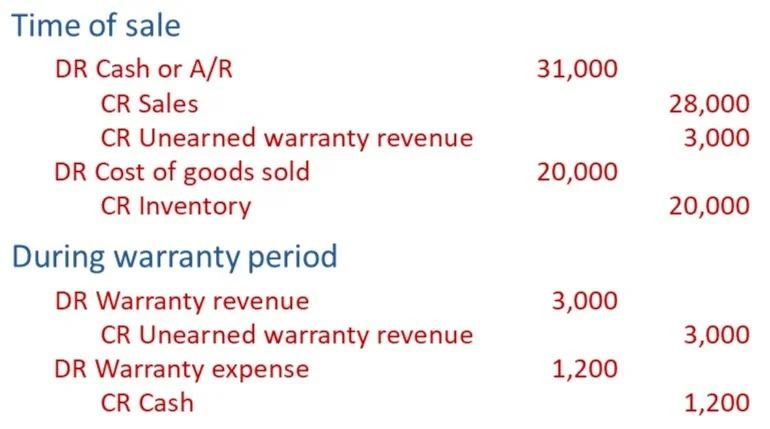

Here is what the bookkeeping looks like:

The amount allocated to the warranty starts out as unearned revenue for the seller. That’s the current liability in this scenario. It is recognized as revenue gradually, over time, regardless of whether any service costs are incurred. Whenever service costs are incurred, either through the provision of routine maintenance or by fixing the equipment when it breaks, those costs are recognized as expenses at that time. They will match the monthly portion of the revenue that was recognized. (In this example, I’ve just shown the total of all the transactions during the warranty period, to emphasize that all the unearned revenue will eventually be earned. This would actually be a series of smaller monthly revenue recognition transactions adding up to the amount shown. The same goes for the warranty expense, which would be a series of smaller transactions adding up to the amount shown.)

Some months, a service warranty may be pure profit because no service work is required. Other months, the service warranty may operate at a loss because the cost of the service work exceeds the small portion of revenue recognized that month. Over the life of the warranty, however, the company will earn a good profit on warranty sales because of the ability to spread the risk over a portfolio of warranties, and by pricing the warranty accordingly.

Advanced Exercise

Here's an advanced exercise I'm going to leave with you. What happens when you've got all of this combined together: the sale of some equipment, a basic warranty on the equipment, and a service warranty where you promise to visit the customer’s site and perform a set number of hours of work to keep the equipment running, all purchased by a customer for a single price?

You can work through this exercise yourself if you think about it. Assume that you actually spent $3,700 on warranty costs, and then do all the transactions from the sale through to the end of the warranty and service contract. Hint: you need to figure out how much of the sale price was for delivering the equipment and how much of it was for servicing the equipment. I’ll provide the solution below.

Summary

Let's sum up what we've covered. We talked about sales discounts. We looked at the direct method, but the thing to focus on, if you want to understand accrual accounting, is the allowance method. We also looked at setting up a returns allowance, including the piece that many textbooks leave out, the right-of-recovery asset that helps keep track of the inventory to make sure that your cost of good sold is accurate.

We then looked at two different kinds of warranties: assurance warranties and service warranties.

I hope this lesson helps you understand a little bit more about revenue recognition. It’s fairly technical stuff, but it helps push you to really understand the basic concepts that are built into IFRS 15 on how to account for contracts with customers.

Solution to Exercise

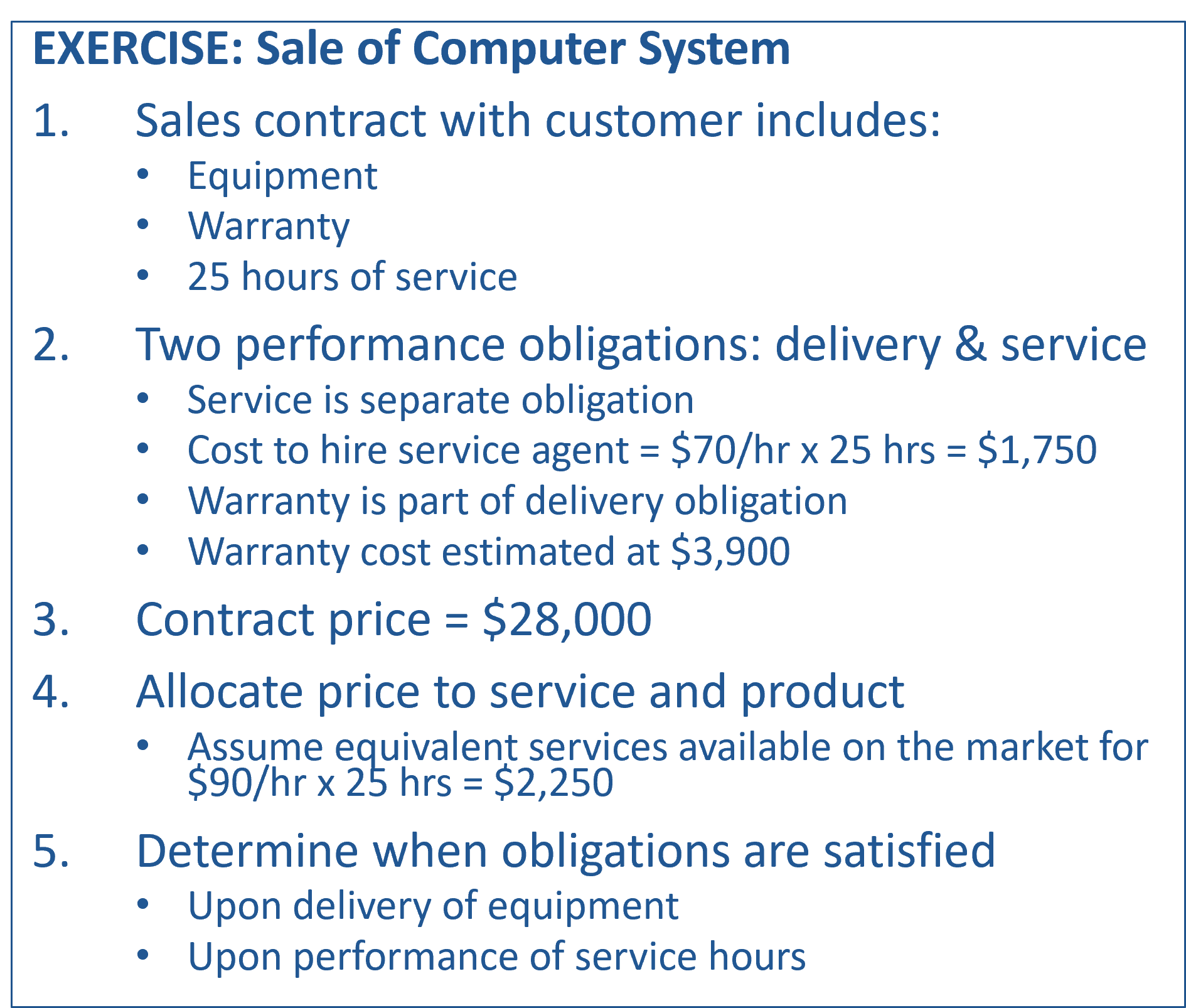

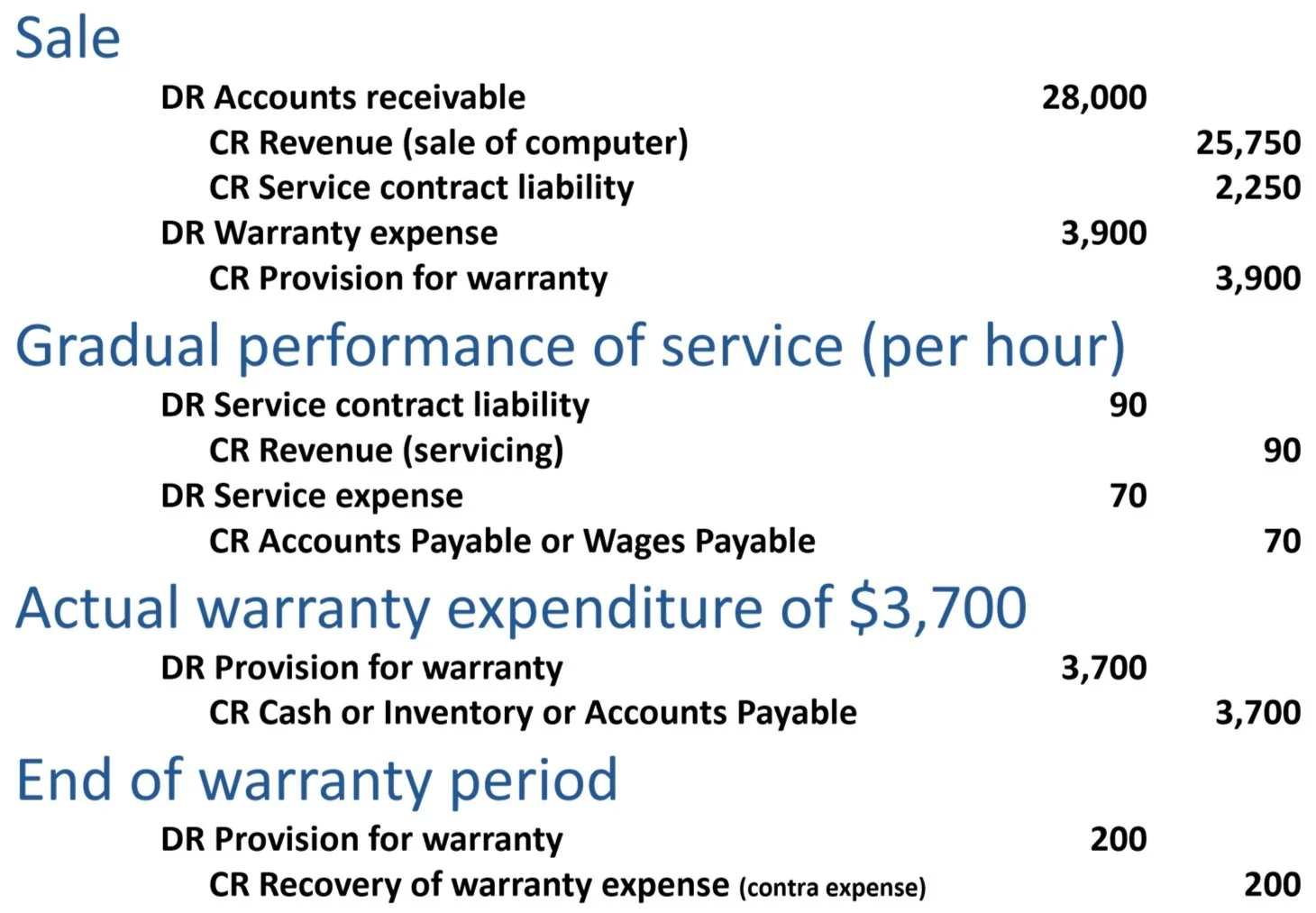

The solution is a combination of all the things we talked about above. The crucial insight, which we get from IFRS 15, is that when you've got a contract price covering a couple of different things, you need to allocate the price over each obligation to the customer. In this case, we have the obligation to deliver equipment and the obligation to perform the service. You need to allocate the $28,000 overall price between these two things.

To do this, you need some way to measure of the value of these two things separately. If you already sell these things separately, you would know what the individual prices are and be able to prorate the $28,000 based on the standalone price. That's how most textbooks do it, but obviously, we have to do things differently here, just for the sake of argument. Let’s assume that you don't sell these items separately.

If that was the case, you’d try to establish the value of each item on the open market. Let’s say that you’ve seen a competitor’s advertisement stating that the customer could buy similar services from them for $2,250. So, we're going to use that as the nominal value of our service contract. It’s 8% of our overall price of $28,000. The remaining 92% of the price will be for delivering the computer.

Over the course of these contracts with the customer, from the original sale to the end of the warranty period, you need to record the sale, the performance of each hour of service, and the actual warranty costs that you experience, which we said would be $3,700, and then finally deal with the end of the warranty period.

And here's what all the pieces look like, laid out:

If you didn't record everything exactly this way, that’s okay. All I’m hoping for is that you did a fairly good job, working through things patiently and trying to figure it all out. Push yourself to think things through, and eventually things will begin to click into place. Remember, you are learning a new language. All right?

Title photo: a derelict house in Toronto. Just a reminder that after any sale, things can go sideways. That’s why we make allowances.