Today I begin a set of articles on Sirius XM Canada, the sole provider of satellite radio across Canada.

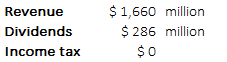

From 2010 when it was formed as a public company until 2016 when it was taken private, Sirius XM Canada took in revenues of $1.66 billion and paid $286 million in dividends to its shareholders. Yet during this time, it paid no income tax. Zero. Not a dime.

And this was all approved by the company’s auditors and the Canada Revenue Agency.

How can this be?

Tax Fairness and Corporations

Profitable corporations that pay little or no income tax have become a serious problem. We have already seen how Apple, the most profitable company in the world, has dodged taxes significantly, paying taxes at a rate far below the US corporate tax rate.

Apple is not the only culprit – or beneficiary, if you prefer. USA Today noted last year that 27 of the top 500 companies in the US paid no income tax. If this seems unfair to you, you are not alone.

Sirius XM Canada is a Canadian example of the phenomenon. To understand how this profitable company could generate such immense dividends yet pay no taxes, we are going to look closely at how it earns money, where that money goes, and how the company is financed.

In previous articles on this website, we’ve laid down a basic foundation of how accounting works. We’ve looked at the income statement, the balance sheet, and the cash flow statement. We’ve also looked at how corporate income tax works. Today, we start to bring all this together in our examination of Sirius XM. If we’re missing any details, I’ll explain them as we go along.

Sirius XM Canada

Sirius XM Canada is now a private company, but from 2010 when it was formed until 2016 when it was taken private, its finances were part of the public record. We’re going to make full use of those public financial disclosures.

Sirius XM Canada was formed in 2010 by the merger of the only two Canadian companies in the satellite radio industry. Like the rest of the media industry in Canada, this segment is highly regulated. The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) governs all broadcasters in Canada, including Sirius XM, to ensure they serve the public interest. The CRTC doesn’t have any say over taxation, but it does control things like how much Canadian content is included in broadcasts and how pricing is structured across Canada to ensure regions are treated fairly.

In 2005, the CRTC issued satellite radio licenses to two companies, in an attempt to set up competition in the fledgling industry. One of the companies was Sirius Satellite Radio Canada, owned jointly by:

Slaight Communications, a private Canadian broadcaster owned by J. Allan Slaight,

the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, Canada’s venerable public broadcaster, and

Sirius Satellite Radio, the US parent company.

The other company was XM Radio Canada, owned by Canadian Satellite Radio Holdings, a publicly traded company. Its major shareholders were:

Canadian media mogul John Bitove, and

XM Satellite Radio, its US parent company.

In both cases, the US parent companies were minority shareholders, in accordance with CRTC regulations for control of Canadian media companies.

The eventual merger of these two Canadian companies was prompted in part by the merger in the US of their respective parent companies. That happened in 2008, but the Canadian companies didn’t merge until 2010. For two strange years, they operated as competitors in Canada that were part-owned by the same US parent.

When they did merge, the shareholders included Bitove, Sirius XM US, Slaight, and the CBC. Again, the US parent was limited to a minority stake. The chart below shows each party's share of the voting rights:

During the following few years, the share percentages shifted somewhat, but Sirius XM US has always remained a minority owner.

The merger in 2010 created a monopoly in Canada over satellite radio distribution. In the next article, we will examine the business model of the company. We will learn how this monopoly has generated huge dividends for the shareholders but surprisingly modest corporate profits.

Photo of my eldest son's dog, Berkeley, taken in Calgary in 2013.