Current liabilities are the financial obligations of a company that management expects to settle within the coming fiscal year. This time element is crucial to understanding how to account for liabilities. It’s not just about time, though. The power of a claimant to assert their claim is also a crucial factor, and this means that the way companies account for liabilities has a political dimension.

Claims on the Company

How do claims on the company arise in the first place? The table below is certainly not intended to be comprehensive, but I've tried to make it detailed enough to give you a sense of the wide variety of claimants that a company has to deal with, and what's at stake with each of them.

Claimants

In the first column, we've got workers, customers, suppliers, creditors, managers, shareholders, and the government. As I said, there are many other possible claimants, but this includes a range of them.

Consideration

In the second column. I've listed what those claimants have offered as consideration for their claim on the company. This is an important factor in accounting for liabilities. If the claimant has provided no consideration, there has not been an economic exchange between them and the company. And I've tried to be fairly general here. So workers have offered their labor. Customers have paid some money to the company. Suppliers have provided goods and services. Lenders have provided money, such as a bank loan or financing for a lease. Managers, like workers, have provided their labor. Shareholders have provided money in purchasing the company’s shares. And government — now what does government provide in consideration for its claims?

Well, it provides the entire context in which the company operates: the roads that its trucks drive on, the legal system in which the company enters into enforceable contracts, even the water and electricity the company needs to operate, if those utilities are publicly owned. Everything that enables the company to exist in society is a consideration provided by the government.

What is Claimed

With these considerations comes the ability of these claimants to stake related claims on the company. Workers have a claim on the company for any unpaid wages or benefits. Deferred compensation, or pensions, represents a claim that workers are entitled to receive at some point in the future.

Customers who have paid money for goods or services are entitled to receive them. There's also a whole series of customer-related claims on the company related to warranties, loyalty programs, and gift cards. We're going to get into those in excruciating detail later in this lesson.

Suppliers, having provided goods or services and having invoiced the company, expect those invoices to be paid. Any invoices that remain unpaid constitute a claim on the company.

Lenders, having loaned money to the company, expect to be repaid, and not just the principal but also interest on the loan. Financing companies that have funded leases for equipment similarly expect to be paid on a regular basis.

Managers, having offered their own labor, are paid slightly differently than workers because they're paid a monthly salary rather than hourly wages, along with their benefits, but these differences are small compared to the most distinctive form of executive compensation: stock options and performance bonuses. In some companies, these forms of compensation might be offered to workers, but generally in our society it’s the senior managers who get stock options or bonuses that are contingent on corporate financial results.

Shareholders, having bought shares from the company, are entitled to dividends from the company, assuming the company does pay dividends. Companies don’t have to, of course. More importantly, shareholders have a claim on residual assets of the company, by which I mean whatever is left over after all the creditors have been paid. While the company is a going concern, this includes everything in the equity section of the balance sheet, including retained earnings — but again, companies are not required to pay this out to shareholders. When shareholders purchase shares on the stock market rather than from the company, what they are buying is a fraction of this claim on the company’s retained earnings, including any future earnings. It’s the possibility that future earnings will increase the value of this claim that makes shares valuable, even though the claim does not have to be settled until the company goes out of business.

The government, having provided the context for the company to operate in, is entitled to income tax; to the withholding taxes, which are the taxes on employee income that employers deduct from their employees’ pay cheques and then remit to the government; and to any sales tax that the company has collected on behalf of the government. Finally, there are any taxes that have been deferred by the company, which we'll cover in a separate lesson. These have to do with timing differences between when a company recognizes its income and when the government expects the relevant income tax to be paid.

It's important to notice that when a company says, "We pay a lot of tax," what they should be referring to is corporate income tax. In some cases, however, companies also include all the withholding taxes that are the company remits to the government. Those are not taxes paid by the company. They are taxes paid by the employees, and they've only been withheld from the employee by the company and then remitted to the government. So let's be clear, when we talk about the tax burden on a company, exactly what we're referring to.

Security

The last column shows what kind of security or leverage a claimant has on the company.

Workers can enforce their claim through employment regulations. They can also take strike action. Customers and suppliers have contract law that they can use to enforce their claim. Lenders also have contract law, but they're often able to secure their claim on specific assets. Having a lien on certain assets means that they could, if push came to shove, sieze those assets and then sell them to somebody else, as a way of satisfying their claim.

Managers, similar to workers, have employment regulations for their salaries, and may turn to contract law if they don’t receive promised shares or bonuses.

What do shareholders have? Well, they have the entire apparatus of securities regulation at their disposal to make sure their claims are enforced. And if those fail, they can always go to court.

The government has its own set of laws around taxes and can enforce those through direct claims or, if need be, pressing charges against a company for failing to comply with tax law.

So this table shows us the variety of ways in which claims can arise and what's at stake when a company faces these claims.

Power

The obvious thing to ask, then, in the face of all of those claims is, what kinds of factors help us distinguish between all those claims. We’ve noted the consideration provided by the claimant, and the framework around the claim that provides the basis for the claimant to assert it. I want you to think beyond these technical aspects of a claim and look at how much power a given claimant might have to insist that a company live up to its obligations.

It’s not enough to have a legal right to something. You also have to be able to operate the mechanisms that will lead to you obtaining it. Various factors influence this.

Claimants have to have some kind of leverage over the company if they expect to be paid? The ability to threaten a lawsuit is meaningless if one does not have the resources to pursue the lawsuit in court. Workers can withhold their labour, but this only works if they are unionized and live in a jurisdiction that supports collective action. Lack of leverage is particularly a problem for claims arising from externalities imposed by the company, where it may be hard for a claimant to prove that their claim has legal standing.

Urgency has to do with how soon the claim comes due. If the company can wait and address a claim later, then it will. It needs to deal with more urgent claims sooner. Urgency also has to do with how important it is to the company that a claimant be paid. A claimant may feel that their claim is urgent, but unless they can impress this urgency upon the company, they are not in a position of power.

Security has to do with the ability of the claimant to enforce the claim. For instance, having a lien on the assets is important for creditors. A claimant may also be given priority under the law, in which case their legal status helps secure their claim. For example, governments often have priority over other claimants when collecting taxes, and employees may be protected by employment laws that ensure employers pay wages before dealing with lower priority claims.

Another factor to consider is the visibility of the claimant, because every company operates under an implicit social license. If a company does not live up to the terms of that social license, then it will suffer consequences of one sort or another. It would not want, for instance, to be seen turning down the claim of an elderly widow who is regarded sympathetically by the public. In contrast, in many countries, Black or Indigenous people may be practically invisible and unable to attract attention to their claims on a company. Similarly, a company may get away with polluting the environment if the pollution goes undetected. Consider the way that mining companies in Canada have, for many years, polluted the waterways on which remote First Nations communities depend. Visibility is political, and is very much shaped by things like media coverage.

Finally, it is worth stating the obvious, that the power of a claimant depends on whether they have the resources to pursue a claim. Having a valid claim and being able to afford a lawyer to assert it are two different things.

Classifying Claims

All of the above factors affect the power of a claimant to enforce their claim against the company. These factors also affect whether and how the claim shows up in the company’s financial statements.

Claims only appear in financial statements if the company has an obligation to satisfy them, and that word “obligation” carries a particular meaning under IFRS:

“An obligation is a duty or responsibility that an entity has no practical ability to avoid.”

This is why understanding the role of power in accounting is important. Claimants who are invisible in society, or who have no resources to pursue their claim, do not create an obligation for a company because the company is able to avoid its responsibility. Under IFRS, a “moral obligation” on the part of the company is not an obligation at all if the company can avoid it. This tells you how unprincipled accounting is.

Furthermore, claims only appear in financial statements if they require the company to transfer economic resources to the claimant. This would seem self-evident, since financial accounting is all about financial values. However, let’s not rush past the implications of this. If a company cannot avoid an obligation, but can settle it with an apology or some other non-economic resource, then the company may have an obligation but it does not have an accounting liability.

Finally, to be recognized by accounting, a claim must arise from some previous action of the company. This includes past sales, where the company may be obliged to provide a warranty. It includes receiving supplies from a supplier, or work from an employee, or money from a lender. This also includes things like active lawsuits against the company, which may not be settled for several more years but are nonetheless based on something the company has already done.

All the claims on a company show up on the right hand side of the balance sheet, either as liabilities or as equity. The distinction between these is longstanding but quite arbitrary. The equity section gives special visibility to a certain class of claimants, the shareholders of the company. From a technical perspective, this has to do with the status of shareholders as having a residual claim on the company. From a political perspective, it has to do with the priority that capitalism gives to those who already have money.

Liabilities

Within the liabilities section, we see a distinction based on time: current versus long term liabilities. This is the same distinction that is made on the asset side of the balance sheet. It has to do with the urgency of the claim. Current liabilities are expected to be settled within the coming fiscal year. A year is a long time, though, and the label “current” does not distinguish between amounts that are due immediately and those that can wait until the company’s operating cash flows bring in more money.

Equity

In the equity section, the claims of shareholders are divided primarily into two categories: share capital and retained earnings. Share capital is what the company raised when it issued shares. It won’t change unless the company issues more shares or buys back some of the shares it previously issued. Retained earnings is the part that is expected to grow and grow and grow as the company earns profit. This is the theoretically unlimited part of the claim shareholders have on the company, because retained earnings could go up indefinitely. Every other claim on the company is limited in some way. Even so, the amount of the shareholders’ claim on retained earnings that accounting recognizes is limited to what has already been earned. Future earnings are only a possibility, and until they actually happen, they remain only a glint in the eye of shareholders.

I’ll just draw your attention to one phrase you will often see in the equity section of a corporation: "accumulated other comprehensive income," or “accumulated OCI.” We'll go over this in more detail when we get to the lesson on the equity section, but for now, think of it as a parking spot for “noisy” fluctuations in the value of assets that are unrelated to the company’s financial performance. Examples include hedges and foreign currency fluctuations, technical things that can wait until we’re ready to talk about them.

Hard-to-Classify Claims

Liabilities and equity account for everything on the right side of the balance sheet. There are two categories of claims that don’t quite fit these two categories, though.

The first is claims that are on the border of the definition of a liability. We’ll deal with them in the lesson on long-term liabilities, but they include liabilities where the value is uncertain, or where the value is known but some aspect of the claim doesn’t quite meet the definition of a liability. For instance, it may be that the obligation is possibly avoidable, depending on future events. The terms provision, contingency, and commitment are used for these sorts of things in financial accounting, and as I said, we’ll go over them in another lesson.

The second category of claims that don’t fit neatly into either liabilities or equity is called hybrid securities. This includes:

bonds with features that make them similar to equity, and

preferred shares with features that make them similar to debt.

Straightforward bonds are definitely considered liabilities, and straightforward preferred shares are definitely considered equity, but financial innovation to attract investor wealth has led companies to create new financial features for bonds and preferred shares that blur the boundary. Bonds might permit the issuing company to delay payment of interest. Preferred shares might have guaranteed dividend payments tied to the market interest rate. Either could be convertible into common shares. These kinds of features make it difficult to classify a security as either debt or equity.

We’ll revisit this topic in the lesson on long-term liabilities. What’s important to understand now is that if the features of a security put it near the boundary between liabilities and equity, not only would managers potentially have discretion to put the security in the category that suits their own needs, but you would need to exercise care in interpreting what that security means. Calculating a debt-to-equity ratio, for instance, will give you a very precise number, but that precision can mask an underlying ambiguity related to the hybrid security. Your D/E calculation might mislead you into making a bad decision.

Time

We’re just about to look at some technical aspects of current liabilities, but before we do that, let's revisit why time is such an important factor in accounting for a company’s obligations. Let’s look at what finance people call the “time value of money.”

The basic notion underlying the time value of money is that if you have the ability to wait to settle a financial obligation, that ability is worth something to you. Not only do you get the benefit of time to plan and get your financial affairs in order, but if you wait long enough, inflation will reduce the real value of the obligation.

If you must pay $1 to somebody right now, that's going to cost you $1. If, however, you have the privilege of paying that $1 sometime in the distant future, you could take the $1 and invest it, earning interest or watching it appreciate in value. You could then pay the $1 when your obligation is due and keep the interest or capital gain that you have earned.

Alternatively, you could invest less than $1, just enough so that it grows in value to $1 when your obligation is due. If you do that, you’ll be able to do whatever you want with the difference between the amount you set aside and your nominal $1 obligation.

What this means for accounting is that if the due date on your obligation is sufficiently far in the future, you should list the obligation at the lower amount, the amount you would theoretically have to set aside now in order to satisfy the obligation later. This is called the “present value” of the obligation. Listing the obligation at its face amount would overstate its economic significance.

We’ll go over present value calculations in a future lesson, but for now, think of it as “interest in reverse.” Investing something now and watching that amount grow year by year, as it earns interest, is moving forwards in time. Moving in reverse, from the date of the distant obligation back towards today, is called discounting. When you do this, the amount shrinks in value, rather than growing. Discounting is easy to do arithmetically — it’s just like the interest calculation, but with division instead of multiplication.

Despite the fact that this is so easy to do, accountants don’t do it for current liabilities. These are always disclosed at face value, not at present value. Why is this? It has to do with the accounting principle of materiality, which we’ve run into before. Adjusting liabilities for the time value of money doesn’t make any material difference when the time period is less than a year. Anyone making a decision that depends on current liabilities would be unlikely to change their mind if the current liability figures were just a tiny bit smaller. So, it’s not worth the effort to recalculate all the current liability figures, and stating them at face value just makes things easier for everyone.

It's not because you can't do the calculation. You could. If a current liability is due in 13 months, you can do a calculation. If it's due in 10 months, you can do a calculation. Why are they disclosed at face value? Not because you don't care about the time value of money, but because the difference in the value that would be shown is not going to be materially different from the face value. So we just don't bother for current liabilities.

Types of Current Liabilities

All right, having considered all those general principles about claims and power and the time value of money, let's talk about all the different types of current liabilities.

You’ll recall that current assets are disclosed in order of liquidity: how quickly they’ll be converted into cash. For current liabilities, the order is less well established. I’m going to discuss them in order of maturity: how soon they have to be settled, which you’ll see quite frequently on balance sheets. Obligations that have to be paid first are typically shown at the top of the current liabilities section, and those that can be paid later in the fiscal year are further down in the current liabilities section.

Line of Credit

A line of credit is a kind of bank indebtedness. In fact, it’s sometimes called that on the balance sheet. Think of it as a negative cash situation. If your bank account goes into overdraft, you’d list it as a current liability rather than a current asset. Companies will normally not net this off against other bank accounts that have a positive balance, allowing you to see the cash situation more clearly.

A line of credit is like having a bank overdraft, but on purpose. It’s not just a result of accidently writing a cheque when you don’t have enough money in the bank. It’s a formal lending facility that has been arranged in advance with the bank. It’s intended to be flexible, to help a company with temporary cash flow problems. Interest is only paid if the company draws on the line of credit, and then only on the amount that has been drawn. If the company has a $100,000 line of credit and withdraws $5,000 from it, daily interest is charged on the $5,000. If the company then pays back $3,000, interest continues to be charged on the remaining $2,000.

At the fiscal year end, the amount owing on a line of credit will be listed as a current liability. The size of the line of credit — the maximum amount available to the company — would be listed in the notes to alert readers that the company can, without any notice, take on that much additional debt if it so chooses. This might be important to other potential creditors in assessing the credit worthiness of the company.

A line of credit is a demand loan. This means that the bank has the right to demand immediate repayment. That’s not what the bank would normally want to do, because it’s in the business of earning interest on loans to its customers. However, the bank has the right to demand repayment if it feels that continuing to lend to the company has become too risky.

A line of credit is thus just a flexible loan. It can be drawn upon and repaid as the company needs. Imagine that a company goes to the bank and says, "You know, every month I get paid by my customers and I'm able to pay all my wages and stuff. The problem is that the wages are due on the 15th of the month, and I often don't get paid until the end of the month. Can you help me out with some bridge financing?" That’s exactly the kind of situation a line of credit is for. It can also, for example, help cover the inventory self-financing period that we talked about in the lesson on inventory.

Lines of credit may or may not be secured. An unsecured line of credit would typically have a slightly higher interest rate. A secured line of credit -- meaning a line of credit where the the bank has a lien on, say, your inventory -- would typically have a lower interest rate, because if need be, the bank could seize your inventory and sell it. Again, accounting is all about power. A company that doesn’t need a loan can get a low rate of interest, while a company that is in a bad bargaining position will often have to pledge assets like inventory as collateral in order to get a loan.

Oftentimes a line of credit will allow the company to only pay the interest on the outstanding balance. With a mortgage, your monthly payments pay off both principal and interest. A line of credit will often allow a company to pay only the interest and leave the balance owing. This would definitely rack up interest costs over the long term, but the bank will be happy with that as long as the company eventually gets around to paying off the amount borrowed.

Accounts Payable

Accounts payable is one of the most common things you're going to find in the current liabilities section of the balance sheet. Mainly this refers to amounts that are payable to suppliers, but if an amount payable to some other party isn't material enough to have its own line in the current liabilities section, it could be lumped into accounts payable. Alternatively, it might be included in something like "Other Liabilities."

Suppliers often offer their customers a short, interest-free period in which to pay their invoices. This makes accounts payable an attractive form of short-term financing for any company. It's sometimes referred to as “interest-free borrowing.” There is still a cost to this, however, because the price of the credit risk that the supplier is bearing is built into the price of the goods you've purchased, because the supplier does need to cover those costs somehow.

Suppliers will often charge interest on accounts that are not paid immediately. In practice, with small businesses particularly, this is a highly negotiable situation. If you call a supplier and let them know that a payment will be delayed a week or so, they will often waive the interest in order to maintain good relations. Obviously, this practice will vary widely depending on industry norms and, of course, the power differential between the supplier and its customers. Suppliers who are in a strong monopoly position don’t have the same need to maintain good customer relations as those that operate in a free market.

Unearned Revenue

Unearned revenue is another very common current liability. This represents payments that have been made in advance by customers for the goods and services that the company offers, but which the company has not yet delivered. The amount of the advance payment will sit there as unearned revenue until the goods or services are delivered, at which point the revenue gets recognized with a debit to the liability and a credit to revenue.

This is a classic example of why a liability is defined as an obligation that involves a transfer of “economic resources” to another party. Liabilities can be settled with the delivery of goods and services, not just cash.

Gift Cards

So far, we’ve only discussed relatively simple liabilities. Now things get complicated, so bear with me. I’m going to go into considerable detail, not because you particularly need to master these details, but so that you can understand the length that accounting goes to in order to calculate the financial value of a company’s obligations.

Gift cards are an example. These are when someone pays money to a store in exchange for what basically looks like a credit card, and then gives that card to someone else as a gift. You may have done this to give a relative a birthday present when you didn’t know exactly what to get them, but you know they like movies, say, so you bought them a gift card they can redeem for tickets to see a movie. Companies often use gift cards as a low-cost way of acknowledging employees: here’s a gift card for $50 you can use at a local restaurant, for instance.

The basic concept of a gift card is that it's like unearned revenue. Someone has given the company some money, and the company has issued a promise to provide goods and services in the future. The twist is that gift cards are not always fully redeemed. People lose them, or they redeem a hair salon’s $100 gift card for an $85 hair cut and then never come back to use up the $15 balance. The hair salon manager never knows when — or even if — the gift card recipient will use the card, so they don’t know for sure how to recognize the revenue on the money they received.

This is where managers have to use their business experience. Given enough history with gift cards (or enough research on other companies who have issued similar gift cards), they will be able to estimate the percentage of the value of outstanding gift cards that will be redeemed. Suppose that on average, 10% of the value of a gift card is never going to be used, for whatever reason. This is called the breakage rate. It’s a lot easier to estimate accurately for a larger company that sells many thousands of gift cards, but even a small company can choose a nominal rate that seems reasonable to the manager.

One way of handling this would be to ignore the breakage rate. That would create a big problem because the liability for the gift cards will grow and grow over time, as that 10% breakage accumulates.

Another way of handling it would be to recognize the breakage immediately upon the sale of the gift card. Suppose customers buy 1,000 gift cards worth $100 each, for a total of $100,000. The company would book $10,000 of revenue right away, on the assumption that the average customer is not going to use that portion anyway. This is better than not recognizing the revenue at all, but it does create a timing mismatch between the recognition of that $10,000 of revenue and the cost of providing goods or services to the eventual users of the gift cards. This violates the matching principle of accounting.

One more possible way of handing it would be to put an expiry date on the gift card. Customers probably won’t like this, so they may not want to buy the gift cards. In addition, this doesn’t really solve the matching problem because if you wait until the expiry date to recognize the $10,000 in breakage, you’ve still got a timing mismatch. It’s just the other way around: part of the gift card revenue will recognized long after the goods and services are provided.

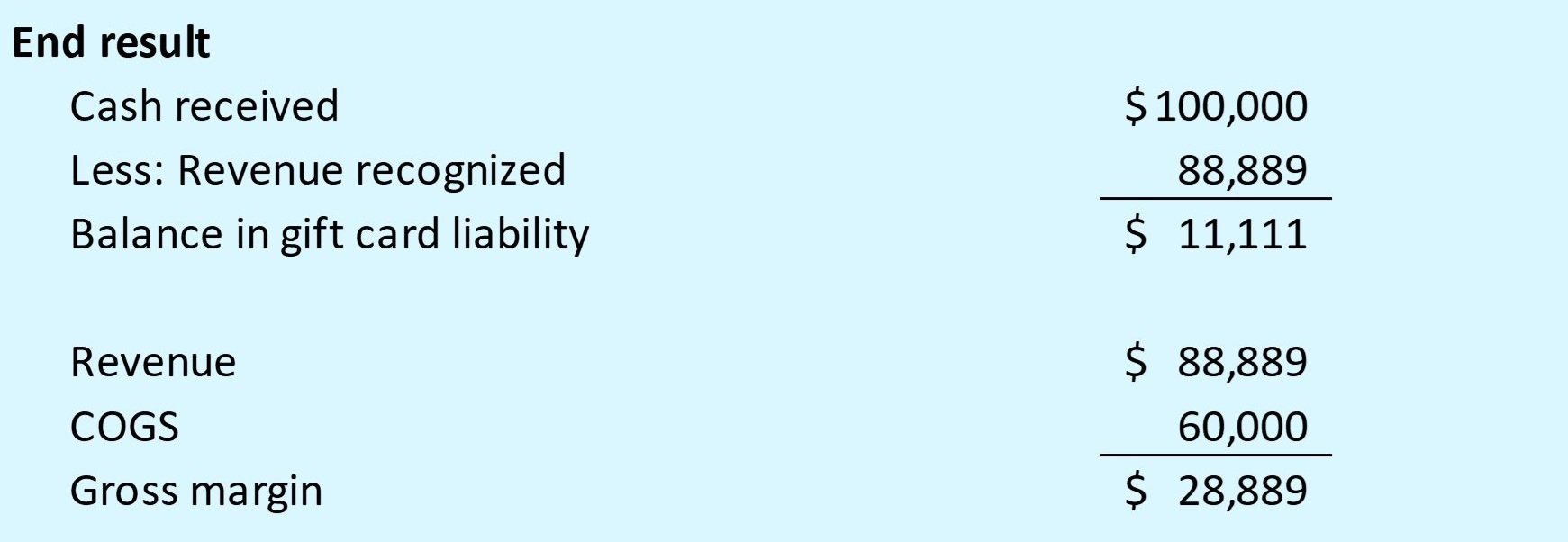

Here, therefore, is how the estimated breakage rate is actually used by companies that do their accounting properly. In the example just given, where the company has sold $100,000 worth of gift cards with an estimated 10% breakage rate, they will recognize the $10,000 breakage gradually as the other $90,000 of value is redeemed. This is a nice methodical way of recognizing the breakage, and it solves the matching problem. However, the calculations and journal entries are a little bit complicated, so let's look at them.

Our starting point is when the cards are purchased by the customers. The figure above shows the $100,000 in cash received, and this is initially set up as a liability of $100,000 because the company hasn't done anything yet to earn the money.

We need some assumptions in order to do our calculations, so let's continue with the assumption of a 10% breakage rate. That means $10,000 will probably never be redeemed, and $90,000 will probably be used to purchase the company’s goods or services.

In order to show how gift cards affect profitability, I'm throwing in one more assumption. The company has not received free money. It will have to expend something on the goods or services that it will provide for the $90,000 of value that will (on average) be redeemed. Let’s assume, then, that the company has a gross margin of 25% on regular sales. I'm labeling that line (g) for “gross margin” so we can use it later on in the calculations.

All right, So what happens when the cards are redeemed by customers? It’s up to the customers to decide to use them, so the company just has to wait for that to happen. Let’s assume that in the next fiscal period, customers use $80,000 of the $100,000 of cards that were purchased. So, 80% of the cards sold are used, leaving 20% still outstanding at the end of the fiscal period. How much revenue should be recognized, and how does this affect the company’s profit?

What we have to realize is that although 80% of the $100,000 of gift cards were redeemed, we are only expecting $90,000 of the gift cards to ever be redeemed. The rest we are expecting to expire unused. So, the $80,000 of goods and services purchased by the customers with the gift cards actually represents $80,000 out of $90,000, or 89% of the expected gift card redemption. (That’s 88.888… repeating, if you use a calculator.)

In the figure, I’ve labeled the $80,000 redemption as line (a). We are going to recognize that amount as revenue, of course, because we’ve now provided the goods and services to the customer. However, we are also going to recognize a portion of the amount we estimated as breakage. We recognize it in the same proportion as the actual redemptions were to the expected redemptions: 89%. Using a calculator, this means that we will recognize 88.88888…% of the expected $10,000 of breakage, which rounds to $8,889. I’ve labelled this as line (b). Since we recognize this at the same time we recognize the redeemed portion of the gift cards, our total revenue recognized at the time of redemption is (a+b), or $80,000 + $8,889 for a total of $88,889.

The transactions for this revenue recognition are shown in the figure above. The revenue is recognized with a credit to revenue, and the debit goes not to cash (because the company was paid back when it sold the gift cards) but to the gift card liability. In this case, we are using up a large portion of the liability because customers redeemed a large portion of their gift cards. If they had used a smaller portion, we would use up a correspondingly smaller portion of the liability.

Along with the recognition of revenue, I’ve shown the cost of goods sold. Given the $80,000 of redemptions and a gross margin of 25%, the cost of goods sold will be $60,000. That’s (a X [1-g]). Obviously, in real life, the company would track the actual cost of the actual goods that were provided when the customers redeemed the cards. I'm just using the 25% gross margin the company enjoys on its typical sales for the sake of completing our illustration.

So where does this leave us?

Well, the company has received $100,000 in cash. We have recognized a big chunk of that, $88,889. This leaves the company with an outstanding gift card liability of $11,111 on the balance sheet at the end of the fiscal period.

On the income statement, things look rosy. Instead of $80,000 of sales and $60,000 of cost of goods sold, we've got $88,889 of revenue minus the $60,000 of cost of goods sold. And this is the big advantage of gift cards. Not only do they enlist regular customers in marketing the company to their relatives, and not only do they provide very favourable cash flows because customers pay well in advance of receiving goods and services, but the inevitable breakage of gift cards that are not fully redeemed means that our gross margin is increased. In this example, instead of a 25% gross margin, we end up with a gross margin of $28,889 / $88,889, or 32.5%. Magic!

Loyalty Programs

Loyalty programs are also complicated. Let's work through the details in order to understand how they affect the balance sheet and income statement.

When you make a purchase at a company that has a loyalty program, it actually has two obligations to you. One is to give you the goods and services that you just purchased. The other is to deliver the value of the loyalty program rewards, whatever those might be, some time in the future.

There are two basic kinds of loyalty programs, internal and external. Internal just means that the company provides the rewards to its own customers. A coffee shop might provide free coffee after every 20 purchases, for example. External means that the company has contracted with a third-party loyalty program provider. You are probably familiar with examples of this in your own country. One that has been popular in Canada for many years is called Air Miles. As the name suggests, they started out offering travel rewards, but now you can use your Air Miles points to get everything from headphones to zoo tickets. Many retail companies in Canada, from high-end liquor stores to low-end thrift shops, offer Air Miles with their sales. Customers can shop at any of these retailers and then use their points on the Air Miles website to get whatever is on offer there.

Internal Loyalty Programs

With an internal loyalty program — I’m calling my fictitious company “Coffee Cup” — the coffee shop gives customers one free cup of coffee for every 20 cups purchased. Typically this would just be a paper card that gets stamped or punched, which you as a customer would keep in your wallet or purse. When you've completed the card, you get a free cup of coffee.

The accounting for this is way more complicated than you’d think, so it’s worth keeping in mind that many small coffee shops wouldn’t bother doing any accounting for this at all. They might not even track the card usage, let alone try to put a financial value on each stamp they issue. In such a case, the “loyalty program” is just a cheap way of getting customers to come back, and it makes sense for a coffee shop because the cost of a cup of coffee is so low that the impact of the program may not be material.

Let’s assume, though, that our company, Coffee Cup, wants to to things properly. The concept of the loyalty program is simple, but the accounting is downright nasty.

Harkening back to IFRS 15, which we discussed in a previous lesson, it’s clear that Coffee Cup has two separate performance obligations to you as a customer. When you buy a cup of coffee and get your card stamped, the company is obliged to give you a cup of coffee now, but also another cup of coffee in the future once you've completed the card.

Here's how the accounting works conceptually. Coffee Cup has to allocate the money it receives over the two performance obligations. The part that is related to the first cup of coffee can be recognized as revenue immediately, along with the cost of goods sold. The part that is related to the “reward” cup of coffee in the future must be set up as a provision. This will be earned later when the card is redeemed. Like gift cards, however, there is a reasonable chance that the loyalty card will never be redeemed, so Coffee Cup has to estimate the breakage rate. So this is like the worst of all possible accounting worlds because we've got all the complication of a gift card program combined with all the complication of an external loyalty program, and they come together in a big mess that we'll do our best to decipher here.

I know this looks complicated, and in fact this is only the first half of the spreadsheet, dealing with the time of selling the coffee; we’ll look at what happens when the loyalty card is redeemed below. However, it is not impossibly difficult to follow these calculations. Here we've got Coffee Cup selling 20,000 cups of coffee during the fiscal year and stamping a loyalty card each time. We're assuming that a customer has to collect 20 stamps before they get a free cup of coffee. That's line (a).

The price of a cup of coffee we're going to assume is $5, because there is a proper barista behind the counter and we’re talking lattes and cortados, not generic drip coffee. That’s line (b).

The cost of a cup of coffee to Coffee Cup, the cost of goods sold, is $1.20. That’s line (c). We'll use that later on so that we can see how the loyalty program affects profitability.

With a loyalty program like this, the Coffee Cup company has to calculate the face value of each stamp or point collected by the customers. In this case, if you were to walk into the store and offer to buy a completed card, you'd have to pay $5.00 because it’s worth one coffee. It takes 20 stamps or points to complete the card, so the face value of each point is $5,00 / 20 = 25 cents. That's like the retail value of a single point. I’ve labelled that as line (d).

The expected rate of redemption for this is 60%. That’s line (e). In other words, Coffee Cup is estimating its breakage rate at 40%. The company is pessimistic about its customer's willingness to come in and use their points. I suppose that makes sense. Lots of people might try out the coffee shop and never come back, but they were given a card and it was stamped once and then they never use it. This might be why the breakage rate is higher than in our gift card example, but since this is all fictitious, it really doesn’t matter.

The estimated actual value of each point, then, is 15 cents. That’s line (f). This comes from the 25 cent face value of each point given to a customer when the card was stamped, times the estimated 60% redemption rate. Another way to look at this is that the company is giving away cards worth $5.00, but since only 60% of them will be redeemed, the value it is having to provide to customers is only $3.00 on average.

So, in our example, Coffee Cup sells 20,000 cups of coffee during the fiscal period. That’s line (g). Therefore, the maximum number of cards that could be fully stamped would be 1,000, which is the 20,000 cups divided by the 20 stamps that it takes to fill up a card. That’s line (h), the maximum number of fully stamped cards. Of course, the actual number of fully stamped cards is going to be much lower than that because, as we noted, a lot of people get their cards partially stamped and then lose them out or never come back to the coffee shop. The number of cards that Coffee Cup expects to be redeemed is therefore only 600, or 60% of the maximum. That’s line (i).

And here, on lines (j) and (k), is where students routinely get thrown by the calculation. If we expect 600 cards to be redeemed, and each completed card can be exchanged for a $5 latte, then the retail value of those cards is $3,000. (You get the same answer if you multiply line g by line f.) However, its not simply a matter of allocating $3,000 of the revenue to this performance obligation, because that would undervalue the performance obligation of providing the initial cup of coffee.

The proper way to do this calculation is to realize that the vendor, Coffee Cup, has promised to deliver $100,000 of lattes at the time of purchase, and an estimated $3,000 of lattes at the time the cards are redeemed. That’s a total of $103,000 of value, but they only received $100,000 from the customers. That $100,000 therefore needs to be prorated over the two performance obligations: 100/103 for the initial lattes, and 3/103 for the lattes that the customers will receive later. The calculation is shown on lines (j) and (k), and it leads an allocation of 97.1% of the revenue to the initial lattes, and 2.% to the later lattes.

If this sounds like a very tiny difference, and one not worth bothering about, you are absolutely right. In this particular example, we’re talking about a difference of $100 out of $100,000 overall revenue, and all that is at stake is the timing of recognition, not the recognition itself. No matter what, the entire $100,000 will eventually be recognized.

In this example, the difference is not material, so Coffee Cup would probably not bother with the intricacies of the calculation. However, if the difference were material to a company, it would certainly be worth doing. If this were Starbucks, which sells billions of cups of coffee a year, not just 20,000, the amount at stake might be enough to change a small loss into an overall profit. Or it might be enough to push total earnings past a threshold where executive bonuses kick in. These are the kinds of factors that influence whether managers “bother” with complicated accounting methods.

You can see the bookkeeping entries for the time of sale. We have $100,000 of cash received, and $97,100 of that is recognized as revenue right away. The remaining $2,900 is set up as a current liability on the balance sheet. I’ve called it “loyalty provision,” but other names could be used, such as “loyalty program liability” or something similar. The cost of goods sold for the 20,000 cups of coffee is shown as well, coming out of inventory.

Okay, having allocated the revenue and seen what happens at the time of sale, let’s look at what happens when the cards are redeemed. I’m going to assume in this example that out of the 600 cards that are estimated to be redeemed eventually, 350 are actually redeemed in the same year as the initial sales. This makes sense because avid coffee drinkers would start collecting points at the beginning of the year and begin to redeem their cards as soon as they had bought 20 coffees. A fair number of the cards could be redeemed well before the end of the fiscal year.

Here is what the calculations look like on the redemptions.

The proportion of the loyalty card provision that we will recognize depends entirely on the customers actual behaviour in using their completed cards. Because Coffee Cup has redeemed 350 of the 600 cards, that’s 58.3% of the cards. We therefore want to recognize 58.3% of the provision as revenue. That works out to $1,691, leaving a balance in the provision of $1,209.

The cost of goods sold for the 350 cups of coffee is $420.

Along with the coffee that was sold initially, we now have revenue of $97,100 plus $1,291, for a total of $98,791. We also have cost of goods sold of $24,000 plus $420, for a total of $24,420. That gives Coffee Cup a gross margin on these sales and redemptions of $74,371, or 75.3%. That is slightly lower than the 76% margin they would have enjoyed without the loyalty program, but presumably overall sales and overall profits are higher because the loyalty program got customers to buy more coffee.

When all the loyalty cards have all been redeemed for these sales, the company will have given out 600 cups of coffee at a cost of $720. They say you can’t put a price on loyalty, but I think we just did.

At the end of this fiscal period, Coffee Cup will have a provision — a current liability —- of $1,209 remaining. That will be used up when the customers get around to using the remaining 250 completed cards. Of course, this is all just estimated, but if Coffee Cup does a good job of its estimates, over time the liability will tend to be a fair representation of their liability for the loyalty program.

If you are interested in playing with these numbers yourself, download the spreadsheet using the link below. As the baristas say, “Enjoy!”

External Loyalty Programs

Now let's talk about an external loyalty program. I want to pick an example I’m familiar with, so (*ahem*) I’ve chosen my local wine merchant. That’s the Liquor Control Board of Ontario, for many years the largest single purchaser of alcohol in the world.

The LCBO used to offer Air Miles with every purchase. Now they’ve switched to Aeroplan, so I’m going to go with that. Either way, the idea is the same. When a customer buys wine or beer or any kind of liquor at the LCBO, they are able to collect Aeroplan points. Customers get asked for their Aeroplan number at the check out counter, and if they have one, LCBO will credit their Aeroplan account with a suitable number of points, depending on what they have bought. If you are not a member of Aeroplan, nothing happens. You just pay for your alcohol and wobble on out of the store.

For customers who belong to the Aeroplan program, LCBO offers points in two different ways. “Base points” are awarded on a customer’s total purchase. “Bonus points” can also be awarded when a particular alcohol vendor, such as a winery, wants to provide an incentive to LCBO customers to buy their particular bottle of wine. LCBO pays Aeroplan for all the points, and charges the alcohol vendor for any bonus points that LCBO issues on the vendor’s behalf. All these costs would be determined based on information collected by LCBO’s point-of-sale system.

External loyalty programs like Aeroplan are accounted for by the retailer in a slightly different way than the Coffee Cup cards. Let's look at what the LCBO says in the notes to its annual financial statement:

For base points, LCBO pays a fee to Aeroplan for each point that it issues. LCBO is acting as an agent of Aeroplan, so basically it is selling Aeroplan points on behalf of Aeroplan. This means that a portion of the money it receives from customers is actually revenue for Aeroplan, not revenue for LCBO. The fee that LCBO pays to Aeroplan for points is therefore not a cost of good sold for LCBO, but a sharing of its revenue with Aeroplan. Another way to explain this is that LCBO is giving customers a kind of cash, Aeroplan points, which can be redeemed for goods and services. If you charge a customer $100 but give them $1 back, you don’t have sales of $100 and cost of goods sold of $1, you have sales of $99. This is something that IFRS is pretty emphatic about.

The opposite situation applies for bonus points. LCBO still has to pay Aeroplan for the points, but it charges the vendor even more for them, so it’s earning a tiny margin on those bonus points. LCBO does not treat this as revenue, though. This arrangement means that LCBO buys alcohol from the vendor, but gets a small rebate from the vendor due to the margin LCBO makes on the Aeroplan points. Netting these out, LCBO is getting the alcohol at a reduced price. Because of this, LCBO treats the margin it makes on bonus Aeroplan points as a reduction in its cost of goods sold, rather than revenue. This makes the accounting for bonus points quite straightforward: the vendor has simply charged LCBO less for its wine or beer.

The base case, though, remains a bit more complicated, so let’s look at it more closely. First, here are the calculations.

As with internal loyalty programs, like coffee cards, there are two performance obligations. LCBO has to deliver the alcohol that the customer has purchased, and also has to deliver the rewards points by crediting those to the customer’s Aeroplan account.

In accounting for this, you have to allocate the money that's been received from the customer over the two obligations. At the same time, you're going to be treating those Aeroplan points that you're giving the customer as a kind of currency, making it similar to a sales discount. The cost of buying the points from the rewards partner therefore goes to a contra revenue account, so that it is recorded as a reduction in revenue rather than cost of goods sold.

In the example, LCBO sells $20 million worth of liquor and gives customers the base Aeroplan points at a specified rate. Let’s assume that the retail value of an Aeroplan point is 5 cents, but LCBO can buy them for 4.5 cents. The customers earn one point for every $5 that they spend, and once they have accumulated enough of them, can use them to purchase air travel or luxury goods through Aeroplan. (These are not actual values but they are close enough for our purposes.)

I’m going to assume a 45% gross margin on liquor. It's actually somewhere around 50% for LCBO if you look at their annual report, but I’m using 45% here to make it easier to tell cost of goods sold and gross margin apart. (If they are both 50% of revenue, the calculation is harder to follow.)

What are the performance obligations here? Well, when the customers bought $20 million worth of liquor from LCBO, they were promised $200,000 worth of points ($20 million divided by $5 is 4 million points, each worth $.05). The total value to be delivered to the customers is therefore $20,200,000, but LCBO has only received $20,000,000 from the customer. Using $20,200,000 as the denominator, you can see that 99% of the performance obligation is for the liquor and 1% for the Aeroplan points.

So how is all this recorded?

Unlike the internal loyalty program, the revenue allocated to loyalty program is not recognized later on when customers use the points, because the external loyalty points have a cash value to the customers. They can use them to purchase goods or services elsewhere. The revenue for Aeroplan points therefore needs to be recognized at the time of sale. Of the $20 million in cash received, $19,800,000 (99%) is recognized as liquor sales and $200,000 (1%) as loyalty program revenue. The cost of goods sold for the liquor, given a 45% gross margin, will be $11,000,000. The cost of the Aeroplan points, purchased by LCBO at 4.5 cents each, goes to a contra revenue account rather than cost of goods sold, as discussed above.

Without the loyalty program, LCBO would have recorded $20 million worth of sales, minus $11 million worth of cost of goods sold. With the loyalty program, LCBO records slightly lower sales because of the revenue allocation to the loyalty program. This reduces the margin on liquor sales slightly, because cost of goods sold was unchanged. The margin on the Aeroplan points is much lower than the margin on liquor, so the overall effect is a slightly lower gross margin.

Why does LCBO do this? Presumably because it provides an incentive for people to come in and shop. If it boosts sales by more than the cost of the Aeroplan points, LCBO will be happy.

Warranties

Warranties are a topic we covered in detail in the lesson on sales related allowances. Let me remind you of the basic issues, so you can see how current liabilities arise from warranties.

There are two kinds of warranties. The first is the assurance warranty. This is the kind that's included in the purchase price and does not require the seller to do anything but fix or replace the equipment if it fails during the warranty period. With this kind of warranty, there is only one performance obligation for the seller: to supply a product that lasts as long as the warranty period. The seller estimates the expense for the warranty service and recognizes that expense at time of sale. The credit side of this transaction goes to the current liabilities section as a provision for the future cost of the warranty service.

The other kind of warranty is the service warranty. It’s the kind where you pay extra for a longer warranty period. It’s also the kind where a vendor of commercial equipment offers to perform routine maintenance over a period of time, to ensure that the equipment operates as expected. This is a service warranty regardless of whether the service contract is included in the purchase price or is offered at an extra charge. Either way, some of the money paid by the customer will not be recognized immediately as revenue. Instead, it will be disclosed on the balance sheet as a liability for unearned revenue, which would be earned as the months go by and the servicing and warranty coverage is provided to the customer. Any portion of this liability that is expected to be earned in the coming fiscal year would be classified as a current liability.

Cable on the left lasted exactly 20,000 km. Probably no longer covered by the warranty.

Other Current Liabilities

Let me briefly note some other current liabilities that you should be familiar with.

Liabilities to the government for taxes payable. This is different than a “provision for future income taxes” or a “future tax liability,” which are often long-term liabilities. Taxes payable is just taxes that have already been incurred and are owed to the government now, but the company simply hasn't paid the government yet.

Withholding taxes are when you collect employment insurance premiums, public pension contributions, and employee income tax deductions off of the employees’ pay cheques, and are responsible for remitting those amounts to the government. They are not the company’s taxes. The company is simply withholding them from the employees, in accordance with employment regulations, and then remitting the money to the government on the employee's behalf.

Dividends payable will show up as a current liability if the company has declared a dividend but not yet paid it to the shareholders.

And finally, there's the famous current portion of long-term debt. This is any portion of the long-term debt of the company that is due to be repaid during the coming fiscal year. The rest of the long-term debt would be disclosed, naturally enough, as a long-term liability. The current portion of long-term debt only refers to the principal that is due to be repaid in the coming year. It does not include any interest expense that will be incurred during that time, because that interest has not yet been accrued.

Summary

That’s it for current liabilities. We’ve discussed some very simple current liabilities and some very complicated ones. Here's what we've covered.

We have gone over the classification of different claims on the company, and we'll explore that topic further in the lessons on long-term liabilities and on equity.

We discussed how power factors into accounting for claims on the company, and how that changes the visibility of various claims on the balance sheet.

We've also looked at specific examples of current liabilities, sometimes in some excruciating detail. We discussed lines of credit, accounts payable, and a collection of possible liabilities to customers, including gift cards, loyalty programs, and warranties. I encourage you to play with the spreadsheets linked below, to help you develop your own understanding of these liabilities.

We also discussed some hard-to-classify liabilities, like convertible bonds, and the time value of money. Both of these topics matter when it comes to distinguishing between current and long-term liabilities.

I hope you found this lesson not too confusing, and perhaps even clarifying. Unfortunately, these topics are irreducibly complicated because of the way IFRS requires companies to handle them. So I encourage you to be kind to yourself and don't get too frustrated if you are having trouble grasping them. These are genuinely complicated topics. Try to understand the basic concepts, first of all, and then secondly, push yourself to understand the calculations by exploring the spreadsheets that I’ve provided.

Title photo: Exposed electrical wiring. A current liability if ever there was.