Long-term assets are those things that a company invests in, such as factories or trucks or a license to use someone else’s intellectual property, that over the coming years will help the company generate income. They are accounted for differently than current assets like inventory or prepaid expenses, which for most companies generate income more immediately, within the coming fiscal year. Time is the key element in this distinction, hence the adjectives “current” and “long-term.”

We're going to go over some definitions about long-term assets, also known as capital assets. Then we're going to talk about the primary accounting issue with long-term assets, which is how to measure the value of an asset after you've bought it. Accountants refer to this as “subsequent measurement.” Next, we're going to look at the tax implications of capital assets, and finally discuss the impairment and disposal of assets.

What are Long-term Assets?

Long-term assets are investments that contribute to earning income over multiple fiscal periods. Now that's a textbook definition. They have to be investments the company has made in something that will earn income. So if you want to buy something and classify it as an asset, it has to either generate revenue or reduce expenses. Otherwise it can’t be considered an asset.

It also needs to be something that will generate this income over multiple fiscal periods, because otherwise it's just an expense this year.

Accounting makes a big distinction around whether an asset is physical or not. Physical assets are referred to as tangible assets. This includes anything that can fall under the rubric of “property, plant, and equipment,” also known as “PPE.” Property refers to land, plant refers to buildings, including factories, and equipment is every other physical asset that the company owns, like trucks and toaster ovens.

Intangible assets, the nonphysical kind of asset, is a bit confusing because this category is subdivided into intangible asset and goodwill. Yes, one of the subsets of intangible assets is called “intangible assets.” Sometimes I think accountants are just messing with us.

Another way to think of this is that intangible assets includes all the capital assets that are not physical, and one of the special intangible assets needs to be distinguished from the rest of the intangible assets because it is unique. That’s goodwill, and I’ll discuss it in a minute.

Elements of Cost for PPE

The phrase “elements of cost” refers to all the costs related to an asset that can be capitalized. Think about the bookkeeping for a second. If you spend money, that’s a credit to cash. The debit has to go somewhere, and we can imagine all the possibilities. The debit could go to:

Liabilities, which have a credit balance. An obvious example here would be using your cash to pay back a loan.

Equity, where the accounts also normally have a credit balance. An example would be using cash to pay dividends, which come out of retained earnings.

The income statement, as an expense. Debits there reduce net income and the retained earnings line in the equity section of the balance sheet.

Current assets, such as inventory or prepaid expenses. Debits there increase current assets, but this is offset by the credit to cash.

Long-term assets. When the debit goes here, long-term assets increase, but the credit to cash means current assets go down, so total assets is unchanged.

When the debit side of a cost transaction goes to long-term assets, we say that the cost was capitalized. If you buy a truck, for instance, the purchase price gets capitalized, but costs incurred to fuel it or wash it are not. They are expensed, which simply means they are recognized as expenses right away. Costs are either capitalized or expensed.

Initial Costs

There is a whole set of initial costs that need to be considered, costs that are incurred at the time of acquiring an asset and are typically capitalized. Let’s think about investing in a building. The purchase price of an existing building would be capitalized, but only after you've taken off any discounts or rebates that you might get for buying the building — for example, if your real estate agent decided to waive part of their fee. You can’t capitalize costs you didn’t actually incur.

If you are paying to have the building constructed for you, the cost of construction would be capitalized, and this would include many, many kinds of costs, from materials and labour to the cost of hiring a construction firm to manage the process.

Any non-refundable taxes incurred as part of the acquisition of the building would be capitalized: sales tax, of course, on construction materials, but also land taxes in some jurisdictions. All taxes included in the acquisition cost are capitalized.

Other necessary costs are also included, and this is where we venture beyond the obvious sorts of initial costs. When you have to pay legal costs, such as registering title to the land, or hiring a lawyer to write up the contracts, all such costs are capitalized as long as they are necessary to the acquisition of the building.

Site preparation, transportation, assembly — these are all costs that might be necessary in constructing a building. This could include dealing with toxic waste on the land before you begin to build, or getting utility services — water, electricity — extended to the property. Those are all necessary site preparation costs. There can be necessary costs even if it’s not a building: buying a brick oven for your new pizza restaurant would mean having transporting the bricks and paying an expert bricklayer to assemble them into an over. Those would be considered necessary costs, and so they would be capitalized.

You often can't use some kinds of equipment without having it inspected and tested, so those costs would also be necessary costs that can be capitalized.

So would the fees charged by an architect or engineer to design your equipment or building.

And finally, the curious thing that is often missed: if you are financing the acquisition through a loan, all the interest costs incurred during the acquisition process — for instance, the long construction phase for a new building or factory — can be capitalized. This might be a considerable amount in a construction project, but for the purchase of a new piece of equipment, the interest incurred between the start of the loan and the installation of the equipment might not be material, so a company might just expense that, even though they could capitalize it under IFRS.

Once the asset is put into use, however, further interest costs cannot be capitalized. They would go straight to the income statement as interest expense.

It should be obvious by now that unnecessary costs cannot be capitalized, but what is an unnecessary cost? Suppose you drop a new piece of heavy equipment and damage it, and perhaps damage the floor of your building, too. The costs of repairing the equipment and the floor cannot be capitalized because they were the result of an accident: they were unnecessary.

Subsequent Costs

How do you account costs incurred for an asset later on, long after you've put the asset into use? Accountants call these “subsequent costs.” The question for us is, are their any subsequent costs that can be capitalized — added to the asset value rather than going straight to the income statement?

Suppose you buy a truck. Down the road, you will need to do maintenance and repairs. Routine maintenance, such as oil changes or replacing the tires when they wear out, is treated as a regular expense in the year which the cost is incurred. Same for repairs, if the truck is involved in an accident.

However, things can be done to the truck that actually improve it in some way, going beyond simply maintaining or repairing it. You could upgrade the suspension so that it can carry heavier loads. You could modify the engine to improve performance or fuel efficiency. These kinds of changes to the truck actually make it a better vehicle, and “betterments,” as accountants call them, can be capitalized. This means adding the cost to the asset value, as opposed to expensing it.

Suppose you spent $100,000 for a truck two years ago, and depreciated it by $25,000 last year. (We’ll talk about depreciation in detail in a moment.) So the book value is $75,000. Now suppose you upgrade the engine, at a cost of $10,000. You can capitalize this cost, making the book value of the truck $85,000. Now, when you continue to depreciate the truck, you simply have a larger amount to depreciate. The expense of the engine upgrade will get spread out onto the income statement in the coming years, along with the original investment in the truck.

So that completes our look at the cost of long-term assets. You’ve got the initial costs, which includes the direct acquisition costs and any other necessary costs, and you’ve got subsequent costs like engine upgrades. All of these costs are capitalized, which means they are added to the asset value and then depreciated or amortized, instead of being expensed when they are incurred.

Basket Purchases

Basket purchases are a favorite of accounting textbook authors everywhere. A basket purchase is when you pay a lump sum to acquire a collection of assets that can be separated from each other. An obvious example is a factory. If you buy a factory, you acquire the land, the building, and the equipment that's inside. You might even acquire any inventory that's still sitting in the building, if that was part of the deal. Land, buildings, equipment, and inventory are all accounted for differently, so you can’t just capitalize the purchase price as one big asset. The price you pay for this factory has to be allocated to each separate class of assets that you acquired.

This can require some judgment. You have to evaluate the fair value of each of part of the purchase. You would probably get an appraisal done on the land and the building, giving you two separate values for those two assets. You could estimate the value of the equipment, or even pay to have it appraised if you needed an objective opinion — for insurance purposes, for instance. You would even assess the value of the inventory, though that could well be the most subjective part of the overall process if there is no obvious market price for the inventory items.

Example: Buying a Factory

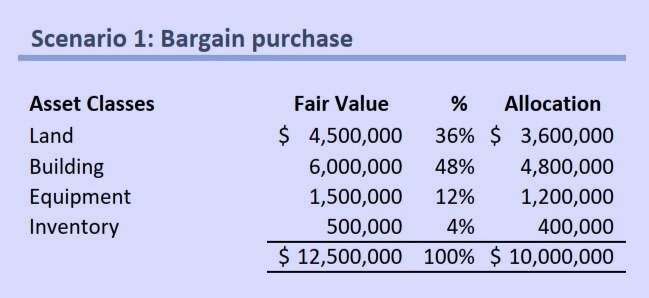

Let’s look at an example. Suppose you buy a factory for $10,000,000, and the purchase includes the land and the building, plus some equipment and inventory that are in the factory.

If the total of the fair values of each of these components is exactly what you paid the seller, your accounting is straightforward. You just distribute the $10,000,000 over the different asset classes according to their fair value and begin to account for each class separately, as appropriate. Land, as we’ll see below, is not depreciated because it doesn’t wear out. It will just sit on your balance sheet at the price you allocated to it. Building and equipment will be depreciated at different rates, because they wear out at different rates. The inventory items will eventually be expensed as cost of goods sold.

But what if the fair values don’t add up to the price you paid?

The first scenario would be if you got everything at a bargain price. This is common because the seller may want to save time and energy by getting rid of the whole package for one price, instead of trying to sell each part separately and having to negotiate multiple deals.

In this scenario, you need to distribute the price you paid over the various asset classes. This is done by calculating the percentage that each asset class contributes to the total fair value. In the example shown, the total fair value is $12,500,000. The fair value of the land is $4,500,000. This is 36% of the total fair value, so the land is assigned an asset value of 36% of the price you paid, or $3,600,000. The same thing is done for each of the other asset classes.

These calculated allocations of the purchase price become the historical cost of each of the components of the purchase. What happens afterwards depends on the way each asset class is accounted for over time, as mentioned.

The second scenario would be if you had to pay a premium to acquire the basket of assets. This is very common when one company buys another, but it is less common when a company simply acquires a basket of assets from someone.

Suppose, though, that you figure it is worth paying extra for the factory for some reason. Perhaps it will eliminate the seller as a competitor in your industry, or perhaps you are just bad at negotiating. In the example shown, the fair value of the assets only adds up to $8,900,000. The fair values will be assigned to each asset class, but the extra $1,100,000 that you paid also has to be accounted for. It’s going to be a debit, because the purchase transaction has to balance. What should you do with this debit?

If you had bought an entire company, you would create a new asset, goodwill, and deal with that as we’ll discuss below. In this case, however, you didn’t buy an entire company, you only bought a factory, so tough luck for you. The debit of $1,100,000 has to go to your income statement as an expense. Hopefully you’ve got a category called “Other expenses” that you can hide it in, because no one wants to admit on their income statement that they overpaid for something.

The point is that when you pay a premium, you do not allocate the premium to the asset classes. That would overstate the value of those assets, violating the conservatism principle of financial accounting.

The third scenario is a bit different, and it is very common. This is when the fair values for the different asset classes come in and they are not specific value, they are ranges of values. You can easily imagine an assessor looking at the land you acquired and not being able to say for sure exactly what it is worth. There is, by definition, no other piece of land that is absolutely identical, and even if there was, it would be hard to say exactly what its value would be. Even if it had sold recently, the market conditions of its sale would be slightly different from the market conditions of your purchase of the factory and the land it’s on. So, the assessor might say that the land is worth between $3,500,000 and $4,500,000. The assessors who were asked to value the building, the equipment, and the inventory might come up with ranges of their own.

Every asset class will have to be assigned a value that is within the range provided by the assessor. It would be inappropriate to assign a value of $2,000,000 or $8,000,000 to the land, in this example. However, it is up to you as a manager to pick a value that is within each range, and you have all the flexibility that the ranges provide you, as long as the total of the values you assign adds up to the purchase price.

This leave an opportunity for managers to pick values that produce favorable financial results. You know that land is not amortized, so the more you allocate to the land, the lower your future expenses will be. The less you allocate to the land, the higher your future expenses will be.

The choice depends on whether you're trying to maximize or minimize your income. Public companies tend to try to maximize their income. Private companies might want to minimize their income in order to reduce their income tax.

So all of these factors will be taken into consideration by managers when they make a basket purchase. You hope that they will make appropriate choices, but they might take advantage of the opportunity to exercise some undue influence on their financial results. That's something to be concerned about if you're an auditor or if you're trying to analyze the company’s financial statements.

Intangible Assets

Intangible assets are, as I said before, assets that have no physical properties. They must be controllable if they are going to produce future economic benefits. If you paid an employee to learn a new skill but have no way to keep the employee from leaving and using that skill elsewhere, you don’t control the future economic benefits. You’ve no doubt heard the phrase, "People are our most important asset." It’s not true. At least, not when it comes to accounting.

You also have to be able to measure the cost of an intangible asset reliably. You may have great team spirit in your company, but it would be highly improbable that you could track the expenditures that led to this important quality, so you can’t account for it as an intangible asset.

There are two distinct categories of intangible assets: those that have indefinite life and those that have finite life. Anything with an indefinite life is subject to an impairment test. The primary example of this is goodwill. Anything with a finite live gets amortized over the life of the asset. Examples include patents, licenses, franchise fees, and quotas. I’ll show you detailed examples of how to account for these later in the lesson.

Intangible assets don’t only arise from being purchased. They can be internally generated, as well, and this creates some interesting and profound accounting issues. IFRS is quite picky about the distinction between research costs, which have to be expensed, and development costs, which can be capitalized. In order to capitalize development costs, you have to be able to demonstrate all of the following:

the technical feasibility of completing the asset

your intention to complete the asset and use (or sell it)

your ability to use (or sell) the asset

how the asset will generate economic benefits for you in the future (that is, you have to show that it will be useful, or you have to show that there is a market for it)

the availability of the necessary resources to complete the development of the asset, including technical and financial resources

the ability to measure the cost of development reliably.

This is a fairly tall order, which is why many companies err on the side of expensing their R&D.

Goodwill

Goodwill is, as I said, a very specific kind of intangible asset. It only arises in one particular circumstance, and that's when one company purchases another. It has nothing to do with your reputation. Accounting doesn’t care if your customers love you.

Goodwill is similar to basket purchases, in that the purchase price for acquiring another company has to be allocated to the fair value of all the assets that you acquire. What makes it different from basket purchases is that you also have to allocate the purchase price to the fair value of the liabilities you acquire. Because when you buy another company outright, you take on their debts, not just their assets.

Once you have allocated the purchase price to the assets and liabilities that you acquired, anything that’s left is classified as goodwill. Goodwill equals the purchase price minus the net assets you acquired.

So for example, if you bought a company for $1,000,000 and there was $500,000 worth of assets and $100,000 worth of liabilities, for net assets of $400,000, that means you have $600,000 worth of goodwill that you need to put on your balance sheet.

Oh, and by the way, there's no such thing as negative goodwill. If the purchase price was less than the fair value of the net assets, you would prorate the purchase price over all of the net assets and record them at the prorated value, rather than at their fair value. That way, the purchase price less the net assets will be zero.

Goodwill is not amortized. It’ s only subject to impairment tests. Every year you have to review the acquisition of the other company and decide whether the goodwill that you recorded still makes sense as an asset. If the acquisition is not working out the way you expected, you should write down (or write off) your goodwill. That means crediting the asset account and debiting the relevant expense account, reducing your net income for the year.

Which brings us to the topic of subsequent measurement.

Subsequent Measurement

Subsequent measurement is a big deal. It’s the main thing you need to learn about if you want to understand accounting for long-term assets. If “subsequent measurement” doesn’t ring a bell, maybe “depreciation” and “amortization” do. That’s what this topic is about.

Subsequent measurement is different from subsequent costs, which we talked about earlier. Subsequent costs are the additional costs incurred over the life of the asset, including those that get capitalized (like beefing up the suspension on your truck) and those that don’t (like oil changes). Subsequent measurement, on the other hand, is about how to account for costs once they have been capitalized, in the years after you incurred them. The word “measurement” specifically refers to the value you should show for the asset on the balance sheet.

Subsequent measurement is important because asset values typically decline over time. Not all do. Land often goes up in value, and so can financial assets. Most tangible assets wear out, though, and most intangible assets (apart from goodwill) have a finite life. Tangible assets can also be damaged, and any asset can become obsolete, whether it’s a computer or a patent. So, there are two issues to deal with: the gradual decline in value of most assets, and any sort of abrupt decline.

There are two ways to do subsequent measurement under IFRS. These are the cost model, where you spread out the capitalized cost of the asset over time in some methodical way, and the revaluation model, where you reassess the value of the asset periodically.

Cost Model

The purpose of the cost model, in all its various guises, is to spread the cost of the asset over the estimated life of the asset. The principles at play here are the conservatism principle, because you don’t want to say an asset is valuable if it is worn out or used up, and the matching principle, because you're trying to roughly match the expense of the asset to the fiscal periods in which it generates revenue.

To apply any kind of cost model, you have to know the capitalized cost of the asset, of course, which we've talked about in some detail already. You also need to estimate its useful life. This could be the number of years you expect it to last, or it could be something like the number of production cycles you expect from a machine press or a photocopier before it conks out. The final thing you need is an estimate of the residual value. This is the value of the asset at the end of its useful life. Is there a market for a used photocopier, for instance, or are you going to scrap it?

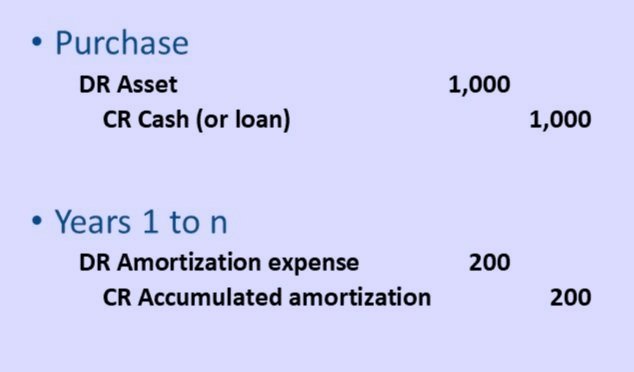

Here's what the journal entries look like. The purchase itself as a debit to the asset and a credit to cash, or perhaps to a liability account for a loan you took out to purchase the asset. In subsequent years, you're going to a debit of some amount to amortization expense and a credit to accumulated amortization. This will gradually reduce the book value of the asset (cost less accumulated amortization), and meter the expense out to the income statement over two or more years.

Terminology

Let's go over the terminology used for the cost model, so that you can learn to speak confidently about accounting. For physical assets that wear out, we use the word depreciation. For intangible assets, we use the word amortization. Those are by far the most common terms. There is one other term, however: for natural resources, such as a gold mine or an oil field, we use the word depletion. All of these words refer to the process of spreading out the expense of an asset over time, using some sort of a cost model.

There are a few other terms to keep in mind, as well:

Net realizable value is what you can get for an asset if you were to sell it now.

Residual value would be the net realizable value at the end of its useful life, when you expect to stop amortizing or depreciating it.

Salvage value is what you will get for the asset when it is completely worn out and you're just going to scrap it. It's a kind of net realizable value, but it refers to the value of the asset when it is no longer fit for purpose.

Choosing a Method

Which amortization policy should you choose? This requires a lot of judgment about how long you're going to use the asset and how you want to distribute the expenses over time. Keep in mind that whatever policy you use, it has nothing to do with your cash flows, because this is purely about accrual transactions. It also has no impact on your income taxes, as I will explain later.

Also, you have to use the same policy for every asset in a given asset class. You can use different policies for different asset classes: you can choose different policies for your buildings, your photocopiers, and your vehicles. However, you must apply the same policy to every individual asset within a class. Otherwise, managers would have too much flexibility to create misleading financial results.

The common choices for the cost model are straight-line, accelerated, and usage-based. Let’s go through these are in more detail now.

Straight-Line

The straight line method distributes the cost of the asset evenly over its useful life. Only the difference between the cost and the residual value is amortized. You simply divide that difference by the useful life, that is, the number of periods you think the asset will remain productive. The assumption here is that the asset, whatever it is, is going to have equal earning power each year.

This method is very common because it's so easy to use. No mess, no fuss, so some smaller companies use this exclusively just because they can't be bothered with the other methods.

This graph shows the amortization expense over the years. With the straight-line method, the expense going to be identical all the way. That's the expenses. If you were to graph the book value, it would decline at a steady rate, which is where the name “straight-line” comes from.

Accelerated

The accelerated model is called “accelerated” because it amortizes the asset faster than the straight-line method. It calculates each year’s amortization expense by multiplying the net book value of the asset by an amortization rate. The assumption here is the asset generates more revenue early on, when it is new, and as time goes by it becomes less and less productive. This makes sense if it is a machine that gradually needs more maintenance, for instance, and experiences more downtime in later life, or if it is a revenue-producing tool like a new printer at a print shop that eventually becomes obsolete and sees less demand from customers.

To use this method, you have to choose some sort of an amortization rate. It could be any percentage you want, but a lot of companies use what's called the double-declining (or double-diminishing) balance method. This just means that the amortization rate is two divided by the estimated useful life of the asset. So for instance, if the asset is expected to last for five years, the rate would be two-fifths, or 40%. (There is another curious way to determine the amortization rate, called the sum-of-years-digits. Example: if the useful life of the asset is three years, 3+2+1=6, so take 3/6ths of the amortization in the first year, 2/6ths in the second, and 1/6th in the third. This one seems like a relic to me; I have no idea if anyone still uses it, given how accounting software determines accounting practice.)

At the end of the first year, net book value is equal to the initial cost of the asset, because there hasn’t been any amortization yet. The amortization expense would therefore be the initial cost of the asset times the amortization rate. This leaves the net book value lower by the amount of the amortization expense. Remember, net book value is initial cost minus the accumulated amortization.

The next year, the amortization expense is once again net book value times the amortization rate, but this time the net book value is smaller because of the accumulated amortization from the first year. The amortization expense for the second year is therefore smaller.

The net book value will continue to decline, so the amortization expense each year will get smaller and smaller, but it will never stop. Note that there is no “useful life” specified in this method. You only stop amortizing the asset when you reach its residual value, at which point there is no reason to continue amortizing because either you are going to dispose of it or the amount of amortization you calculate is no longer material.

The graph of amortization expenses for accelerated amortization shows that the first year has the largest amortization expense. Each subsequent year, the expense is a little bit less and a little bit less, gradually tailing off towards zero. If you were to graph the net book value instead of the amortization expense, it would also start off high and decline quickly, then level off as the amortization expenses get smaller and smaller.

Usage-based

With a usage-based cost model, the calculations are slightly more complicated, but it's still fairly straightforward conceptually. You first have to estimate how many units of production the asset is capable of over its lifetime. This is something the engineers who built it would know, so you would probably have taken that into account when you made the decision to buy it. A photocopier might be rated to last 100,000 copies. A drill press might be rated at 1,000,000 cycles.

Like the straight-line method, you are amortizing only the difference between initial cost and residual value. However, instead of dividing it by the number of periods the asset will be used, you divide it by the number of units you expect it to produce over its lifespan. That gives you the amortization expense per unit. Every period, then, the amortization expense will be the number of units the asset produced during the period, times the unit cost.

This means, of course, that the amortization expense will fluctuate depending on usage. This is great when the revenue the asset generates is directly related to the number of times it is used each period.

A graph of the yearly amortization expenses will of course depend completely on usage. This graph is just an example. In year one, the asset was used a moderate amount. In years two and six, it was used heavily. The other years it was not used as much.

Amortization Conventions

There's a little wrinkle to consider in accounting for long-term assets. What happens when you acquire the equipment or the asset partway through the fiscal year? Do you take the full year of amortization, or none, or a portion of it? The advantage of the all or nothing approach is that the calculations are simplified. No complications to worry about. You could just do the first amortization calculation when the asset is a year old, instead of at the fiscal year end. That is certainly easier if you are doing things by hand, but it makes no sense to be worried about calculations when accounting systems are computerized. Also, this approach would create incentives and disincentives for managers to time the acquisition of assets to manage their financial results.

A computerized accounting system can easily use the start date to calculate a portion of the first year of amortization — so many 365ths of the expense — and lots of companies certainly do exactly that now. However, accounting is riddled with conventions that were developed in the days of doing things by hand. One such convention is the half-year rule. This says that no matter what your start date — and remember from our discussion of initial costs, the start date is the date the asset goes into use, not the date it was purchased — no matter what your start date, you take exactly one half of the first year’s amortization. Whatever method you are using, do the regular calculation for a full year of amortization or depreciation, and then cut that in half. The following years, do the regular calculations. With the straight-line and usage-based method, you’ll have an additional half-year of amortization to tack onto the end, and with the accelerated method you’ll just reach your residual value a year later, when the amortization expenses are already small and the difference may not even be material.

The half-year rule is used for tax purposes in many countries, expressly for the purpose of eliminating the opportunity to manipulate taxable income. Otherwise, it only lives on as a convention of accountants. Other conventions exist, such as the half-month rule. All that means is that if the asset is acquired in the first half of the month, you take the full month of amortization, and if it's acquired in the second half of the month, you don't take any amortization for that month.

Revaluation Model

The point of the revaluation model is to arrive at asset values that are more relevant than ones based on historical cost. The revaluation model is, in its simplest form, simply a matter of assessing the value asset directly each year, rather than making assumptions about how the asset value will change over time, as is the case with the cost model.

It's not strictly necessary to reassess the asset value every year. You could, for instance, reassess it every three or four years, and then in between, amortize or depreciate it in the same way would under the cost model. This is a hybrid approach that offers some of the relevance of the revaluation model, while avoiding some of the cost of reassessments. Real estate appraisals, for instance, are common, but they cost money, so a hybrid approach might be appropriate for companies that want to recognize gains on the appreciation of real estate investments, without paying for a new assessment every year.

Another thing to keep in mind is that you don't get to pick and choose individual assets to be revalued. If you own several buildings, for instance, you can't only revalue the ones that went up in price. You have to apply the revaluation model to the entire asset class, if you choose to use it.

You could, however, use the revaluation model for buildings and the cost model for vehicles, for instance.

As it turns out, revaluation is the model that IFRS would like everybody to be using for everything, because it produces more relevant values than anything based on historical cost. However, companies don't use it because it can be expensive to implement if there's no immediate liquid market where people can just look up the price.

Such a market does exist, of course, for financial assets like stocks or bonds. We'll go over how to account for these often volatile assets when we get to the lesson on investments in other companies. The important thing to note here is that the revaluation model could see the asset value going up or down. If it goes up, that's a form of income. If it goes down, that's a form of expense. You have to account for these impacts on your net income. The key question is, do you show this impact right away, or should you delay recognition until the time you sell the asset and the gains or losses are realized? The way to delay recognition is to temporarily store the debits of the losses and the credits of the gains in the equity section of the balance sheet, without recognizing them on the income statement.

Look ahead to that lesson now if you are interested in the details.

Now with the incentives that are there for managers to try to produce inflated values for their assets and increase their net income artificially, there are a couple of ways in which the increase is parked for later appearance on the income statement. One of these would be if the value of the asset goes up above historical cost through the revaluation, then the difference would be stored in other comprehensive income rather than as income itself.

And if it's not stored in other comprehensive income, it could be parked in very similar fashion under something called a revaluation surplus. Both of those would be in the equity section, and they would not be realized as income until you actually dispose of the asset.

Non-IFRS Models

Having looked at what's allowed under IFRS — the cost model and the revaluation model — let's have a quick peek at some alternative models for subsequent measurement. These are useful for internal management purposes or for producing alternative financial statements for a specific audience, such as a creditor, but they cannot be used for a company’s regular financial statements under IFRS.

One of the alternative models is replacement cost. It's quite important for insurance purposes, because if you want to get an asset insured, the insurance company needs to know not what you paid for it, but what it's going to cost to replace it. This question cannot be answered easily if the asset in question is completely unique and can't be replaced, like a work of art. However, if you are going to be calculating replacement cost, you need to look at all the costs necessary to replace the asset. Just as when you're capitalizing an asset in the first place, you have to include all the necessary costs, not just the purchase price.

The value-in-use model is extremely important for understanding what the asset is actually going to produce for you in the future, so it is used by businesses when making purchase decisions. Value in use is basically the present value of all future cash flows related to the asset. (“Present value” is the idea of discounting future cash flows to take the time value of money into account. Arithmetically, it's the opposite of compounding interest. Instead of multiplying by an interest rate, you divide. It is working backwards from the future value using a discount rate, instead of working forwards using an interest rate. We’ll go over this in more detail when we talk about long-term liabilities.) The present value calculation should include not just the future cash flows the asset generates directly, but also the ones it allows you to avoid. Something can be an asset if it leads to cost savings, It’s not necessary for it to generate revenue.

Recoverable amount is the value of assets if the company that owns them is no longer a going concern. This is the valuation model imposed on a company when it goes into receivership. It’s also used for impairment tests to ensure that the asset is still worth the amount shown on the balance sheet, and for determining the value of an asset as collateral on a loan. Recoverable amount is the greater of value-in-use and net realizable value.

Tax Implications

You’d think that a company’s amortization policies would have a huge impact its taxable income. This is not the case, because tax authorities aren’t stupid. They realize that managers would happily pick amortization policies to minimize tax if it suited them, so the tax regulations in most countries takes the decision out of managers’ hands. Managers can still use whatever amortization and depreciation policies suit them for general financial reporting purposes, but on the company’s corporate tax return, they have to use methods specified by the tax authority.

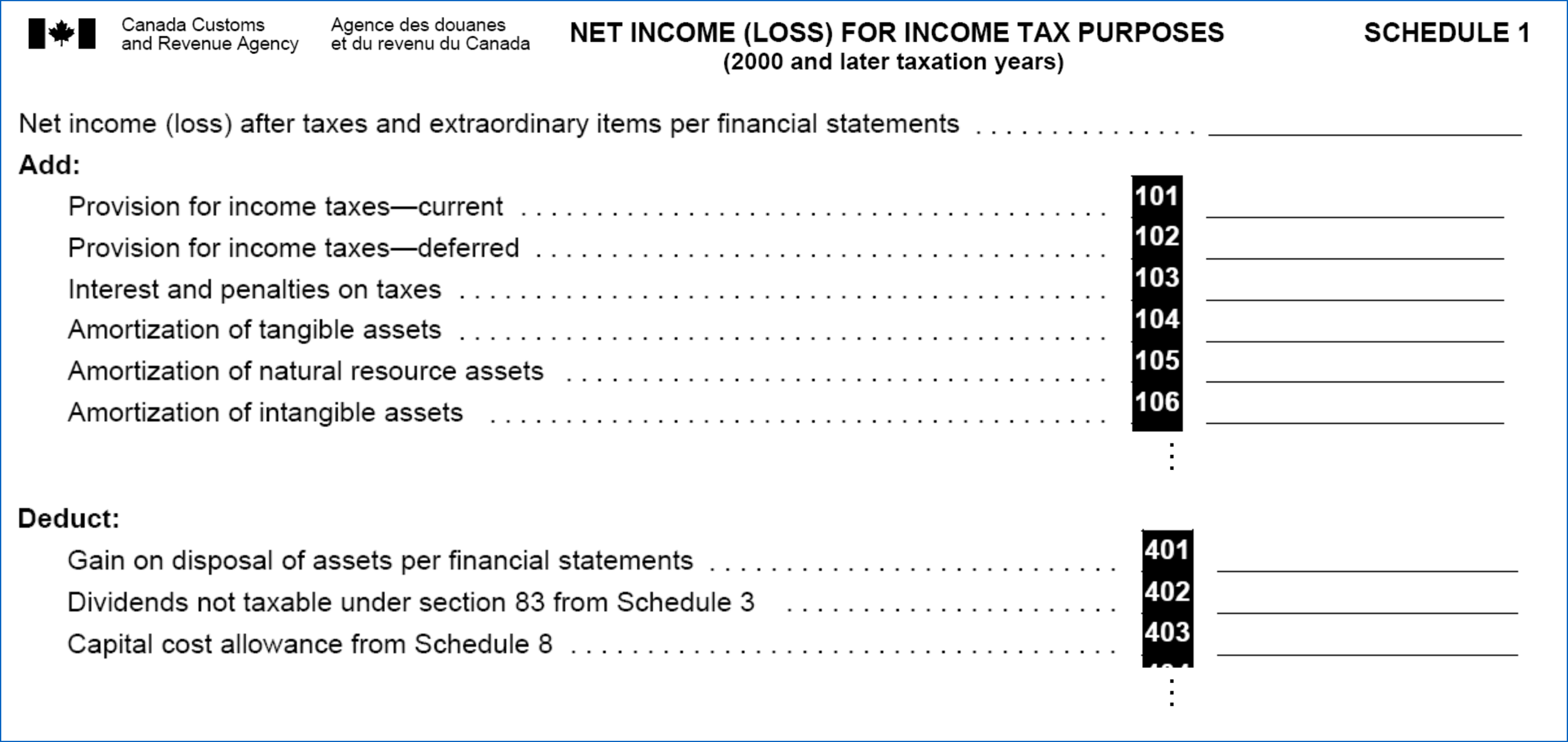

Here is part of the Canadian corporate tax return form. It’s from the year 2000, and I've chosen to use an older version of this because it’s clearer than the current one. I’ve also abbreviated it to focus on the amortization parts of the tax calculation.

You'll notice that it's divided into two different sections. The first section requires the company to add back a whole list of expenses (19 in all, before I cut out some lines and put in the ellipses) that were deducted from net income on its income statement. The second section stipulates the deductions from income that are allowed for tax purposes. (The unabbreviated list that I started with goes on and on.) So, basically the company has to undo its own calculations and redo them the way the tax authorities prescribe.

The thing I want you to focus on is that the form requires a company to add back all the amortization expenses for the year for all its assets: tangible assets, natural resource assets, and intangible assets. That’s all of them. So, regardless of what model you use for depreciating your assets, your calculation will be ignored. Then, in the deduction section, the amount that is used instead is called capital cost allowance. This name refers to the result of the depreciation calculation mandated by the tax authorities. In Canada, a cost method and a depreciation rate are specified for each class of asset. For example, vehicles use a declining balance method with a 30% rate, while patents use a straight-line method with a 5% rate.

Also, as mentioned earlier, the half-year rule is used in many countries to avoid creating opportunities for tax manipulation.

Tax authorities can allow higher tax deductions for classes of assets that the government wants to prioritize. It might want to encourage investment in green technologies, for example. This doesn't mean that a company gets to deduct more over the life of such assets. It just means that the company gets a higher deductions than normal in the earlier years, and lower deductions later. All that happens is the company’s tax payments get deferred somewhat, but that is often enough of an incentive to sway corporate decisionmakers.

Impairment and Disposal

All right, let’s turn our attention to some real issues with long-term assets. What happens when an asset gets permanently damaged somehow, or becomes obsolete? We’re talking about a situation where the asset is no longer worth as much as it says on your balance sheet. Accountants refer to this as impairment. And what happens when an asset is reaching the end of its useful life and you decide to dispose of it? Let's look at those calculations and the journal entries that are used for these situations.

Impairment

When the asset is permanently impaired, you need to reduce the net book value shown on your balance sheet, which is often referred to as the carrying value. This is the conservatism principle of accounting in action. The carrying value of an asset should be reduced to its recoverable amount, which we discussed above. That’s the greater of (a) the asset’s fair value minus selling costs, and (b) its value in use. You’ve seen these terms before. Fair value is the price you could get on the open market if you were to sell it. Selling costs are any shipping fees and commissions you might have to pay if you sell it. And value in use is the present value of any future cash flows generated by the asset if you continue to use it instead of selling it.

The process of reducing the carrying value of an asset in your accounts is called “writing down” the asset. If the asset is determined to be worthless and is written down to zero, we say that it is “written off.”

The journal entry for this is identical to the journal entry for depreciating the asset: debit to depreciation expense, credit to accumulated depreciation. All you are doing is recording an extra bit of depreciation because the asset has, in effect, worn out faster than you predicted. Note that if an asset is damaged but the damage can be fixed, there is no write down. You just have an expense for the repair; the carrying value is unaffected.

One thing worth noting about IFRS is that companies can reverse impairments later on if the value of the asset goes back up. This pretty much contradicts the idea of an impairment being permanent, doesn’t it? IFRS allows this because it is very much focused on the relevance of financial information. If an asset goes down in value, and then up in value, investors and other people who use the financial statements should know about it so they can make good decisions. The issue is, who gets to say what the asset value is? If the value can be determined independent of the managers’ own estimates of its value, then allowing reversals is a very useful way of handling impairments. If, however, the value can’t be determined independently and all we have to go on is the managers’ say so, it’s a very bad way of handling impairments.

The language of International Accounting Standard 36 (IAS 36) says there are two possible indications that an impairment may no longer exist: external sources of information, and internal sources of information. The former is what you would expect. It includes changes in interest rates or technology or the law that make an asset increase in value. You can imagine owning a mineral deposit that has been exhausted and written down, and then new technology emerges that can get more of the mineral out of the ground cheaply. The mineral deposit would suddenly become valuable again.

The latter category of indications sounds ominous, though, at least to me. Internal sources of information include “evidence from internal reporting” to indicate the asset will now be profitable. That’s all it takes to justify reversing a previous impairment. I can’t see how any self-respecting earnings manipulator could resist the opportunity this provides to fiddle with the financial statements.

Disposal (Gains and Losses)

When an asset is disposed of, whether it's sold or just scrapped, you have to remove the asset from your books entirely. This means getting rid of the historical cost from the asset account and the accumulated amortization or depreciation from the contra account. Whatever proceeds you get for the asset when you dispose of it are almost certainly not going to be exactly equal to the carrying value of the asset. It could happen by coincidence, but it is unlikely because it is almost impossible for you to predict, when you purchase an asset and set up its amortization schedule, what its eventual book value is going to be when it comes time to sell it.

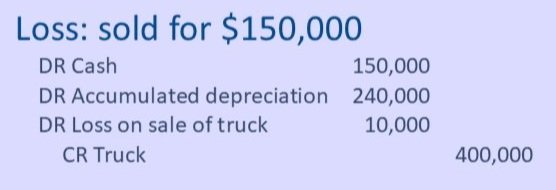

Here is an example of a truck that cost $400,000. It's been amortized at $80,000 per year for three years. The accumulated amortization is therefore three times $80,000, or $240,000, leaving a carrying value of $160,000.

The first scenario would be when it’s sold for more than carrying value, say $200,000. If that's the case, you'll record a gain on the disposal of the asset. Here is the transaction. There is definitely going to be a debit to cash of $200,000. And, we know what the the historical cost and accumulated amortization are for the truck, so those accounts are credited and debited accordingly, to bring their balances to zero. That leaves us needing a credit of $40,000 to balance the transaction. This is credit is the only part of the transaction that affects the income statement, where it is disclosed as either a “gain on disposal of assets” or “other income,” depending on how material the gain was for the company. The more material the gain, the more likely the company is to disclose it on its own line on the income statement.

The second scenario would be if the truck is sold for less than its carrying value, say $150,000. In this case, you’d record a loss on the disposal of the asset. Here is that transaction. We know that we have $150,000 of cash coming in, so that's a debit to cash. We know we have to eliminate the historical cost and the accumulated amortization on the truck, just as we did before. In order to make this transaction balance, we need a debit of $10,000. That will show on the income statement as a “loss on disposal of assets,” or as before, it might be lumped in with other income.

So what does a “gain” or “loss” mean? What does it contribute to the story being told by the company in its financial statements? Is the company trying to say that it is good or bad at selling assets? Perhaps. But another way of looking at it is that the company is telling us how good it is at predicting the future value of its assets. If it did a perfect job, there would be no gain or loss. The cash received on disposal of the asset would match the carrying value. A gain just means that the company depreciated the asset too quickly, and it needs to reverse some of the depreciation expense it previously recorded. A loss just means that the company depreciated the asset too slowly, and it needs to add more expense to the income statement to ensure that the total cost of the vehicle (initial cost less the proceeds on disposal) gets included in its net income.

Summary

Let's review what we've learned about long-term assets.

We looked at the definition of long-term assets, also known as capital assets. They are investments that produce income over multiple years. If they don't produce income, they're not considered an asset. If they don't produce it over multiple years, then the cost should just be recorded as a regular expense.

We looked at subsequent measurement, which is the problem of what value should be disclosed for an asset. We learned several different cost models: straight-line, accelerated, and usage-based. All of these methods systematically spread out the cost of an investment over the period of time in which you are making productive use of the asset.

We also looked at the revaluation model, which is the alternative to the cost model under IFRS. The revaluation model depends on having some sort of an independent measure of the value of the asset, either by being able to look up its price on a liquid market or by hiring an independent assessor to evaluate the asset.

We touched on several non-IFRS models, namely replacement cost, value in use, and recoverable amount. You can't use these on your financial statements if you are following IFRS, but they can be very useful ways of looking at your asset value as a manager, or if you are talking to a lender or an insurance company.

We looked at the tax implications of your amortization policy and we learned that there are none. All of your amortization work gets backed out in the tax calculation, and instead you use the capital cost allowance for that particular class of assets, as stipulated by the tax regulations. And please note that "capital cost allowance" is the phrase used in Canada. Other countries would have a different word for it. In the USA, the IRS simply uses the word “depreciation,” but I’ve used the Canadian wording to make sure you realize that the deduction you claim for income tax purposes will often be different from the depreciation shown on your regular income statement. In most countries, this happens because the government wants to eliminate opportunities for managers to game the income tax calculation, and it may want to use the calculation to incentivize certain kinds of investments by the corporate sector.

Finally, we looked at impairment and disposal of assets. Impairments is are permanent. Disposal leads to a gain or a loss, depending on whether the proceeds from the disposal were greater or less than the carrying value of the asset.

This has been a lot to take in, but it’s a crucial topic. Take the time to do some exercises to practice these kinds of calculations. Then, when you are ready, go on to the next lesson.

Title photo: Not a long-term asset.